Sunday, May 20, 2001

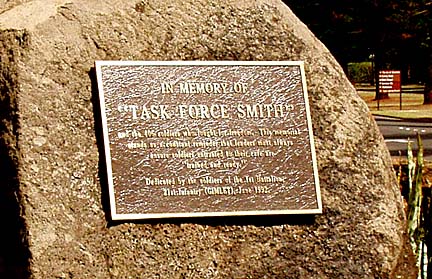

Ready...or not CLOSE BY the barracks of the 1st Battalion, 21st Infantry at Schofield Barracks stands a modest gray stone monument dedicated to Task Force Smith, whose ill-trained and poorly armed soldiers were thrown hastily into the Korean War in 1950, very quickly to suffer horrendous casualties in killed, wounded, or missing in action.

The battle for Makua Valley resumes

this summer as the Army heads

back to the training site and

Hawaiian activists head

for courtBy Richard Halloran

Star-BulletinShortly after the North Korean surprise invasion of South Korea, Lt. Col. Charles B. Smith was awakened in his quarters in Japan, where he commanded peacetime soldiers on occupation duty, and told to load his understrength battalion aboard aircraft bound for Pusan. The sudden call to go to war, Smith said later, was a vivid reminder of Pearl Harbor; he had been a company commander at Schofield Barracks on Dec. 7, 1941, when Japan mounted its raid on Pearl Harbor, and had led his troops to defensive positions at Barbers Point.

In Korea, Smith's 406 soldiers were joined by another inadequately trained band of 108 soldiers with six artillery guns, plus a handful of medics, for a total of 540. They comprised Task Force Smith and moved north by train and truck to a line of hills south of Seoul, where they dug in and were soon struck by a North Korean force of 20,000.

The inscription on the Schofield Barracks memorial

to those who lost their lives in Korea

with "Task Force Smith"

Task Force Smith fought well for seven hours and started an orderly retreat. Then the badly trained soldiers broke and ran, leaving behind weapons and equipment. Some took off their boots to wade through rice paddies, others straggled through the hills, and one man eventually made his way south in a Korean sampan. Smith counted about 150 dead, wounded, or missing, a 27 percent loss in an Army that counts 10 percent as excessive.Today, the plaque on the monument at Schofield Barracks says: "This memorial stands as a constant reminder that leaders must always ensure soldiers entrusted to their care are trained and ready." Or, as a watchword initiated by Gen. Gordon Sullivan when he was chief of staff of the Army in the early 1990s holds: "No more Task Force Smiths."

To prepare soldiers for battle is the purpose of the Army's training in the Makua Valley that juts inland from the Waianae Coast. There, companies of 150 soldiers experience the sounds and smells -- and the confusion and rush of adrenalin -- of live fire exercises that generations of infantrymen assert are vital to success and survival in combat. The Army says it makes such training as realistic as possible within the bounds of safety.

The Army contends that there is no alternative to Makua in Hawaii. Firing ranges at Schofield are too small, live fire is not permitted in Kahuku, the rugged terrain of Kawailoa is good for maneuvers but dangerous for live fire, and transporting soldiers, arms and equipment to Pohakuloa on the Big Island would be time consuming and expensive.

Many residents of the Waianae Coast, who have formed an association called Malama Makua, see it differently, on at least five counts:

>>Cultural or religious: The valley is the location of many heiau, or places of worship, and archeological sites that are cherished by Hawaiians.

>> Environmental: Makua is home to endangered species of plants and animals that they think should be preserved.

>> Property rights; owners or potential owners covet a lovely valley.

>> Safety: Trucks loaded with live ammunition must drive up the Farrington Highway alongside residential areas to get to the valley.

>> Disturbances: Soldiers make ear-splitting noise all day and well into the night when they fire machine guns while helicopters whirr overhead.

After a hiatus of two years and eight months enforced by court order, the Army announced last week that it had completed an environmental assessment of its training regime in the valley and found that it would have no significant damage on the cultural sites or the environment, and proposed to resume training sometime this summer. The layoff, the Army maintains, has caused a serious degradation in the training of the 25th Infantry Division at Schofield, the Marines from Kaneohe and National Guard units.The president of Malama Makua, Leandra Wai, called the Army's decision "an insult" and recited a litany of complaints of desecration and destruction. The association's legal counsel, David Henken of Earthjustice Legal Defense Fund, said Malama Makua would seek a court order to prevent the Army from returning to training and would appeal any ruling that went against it. Malama Makua has demanded that the Army undertake an environmental impact statement, which is more comprehensive than an environmental assessment and would cost $2 million to $4 million and take two years to complete.

Malama Makua has about 100 active members and claims support from a thousand more. Volunteers do most of the work and funds come from donations; a fund-raising committee has been established to seek support from foundations. Earthjustice, which also exists on donations, renders free legal advice, but Malama Makua must pay for operating and overhead costs.

The outlook is for a continuation of a long legal struggle between Malama Makua and the Army whether the court permits the Army to resume training or not. The dispute is almost certain to reach an appellate court and possibly the U.S. Supreme Court.

This conflict reflects similar clashes across the nation; all have causes in common even as each has its own reasons. On Cape Cod in Massachusetts, for instance, an environmental group has demanded that the National Guard restrict its operations at Camp Edwards. Near Dyess Air Force Base in Texas, the main base of B-1 bombers, Fisher County commissioners have objected to the noisy airplanes flying over their homes. At Fort Irwin, Calif., where large formations of tanks train in the Mojave Desert, environmentalists have sought to restrict operations to protect a desert tortoise.

These confrontations are rooted in one or more of five fundamental causes:

First is the military need for larger training areas because rifles, guns, mortars, and missiles can be fired farther than was the case 40 or even 20 years ago. Moreover, units need to spread out as the tactics of maneuver require greater space. Survival against enemies with highly lethal weapons requires soldiers to extend their formations and commanders to learn to control their forces over wider areas.

Second is that towns and cities that were once a long way from military bases out in the boondocks have expanded toward them as the population of the United States has grown. Thus, a training base in the middle of nowhere 40 years ago may now have a neighborhood next to the main gate.

Third is the anti-military legacy of the Vietnam period of 25 to 35 years ago. The protesters of the late 1960s and early 1970s are now the leaders of their communities and many carry the same sentiments as they did in their youth -- and have passed on their ideas to their children, the young anti-military dissidents of today.

The fourth has been the growth of the environmental movement, which has become an ingrained if contentious element in American society. The armed forces, whose duties often call on them to break things and kill people, are the antithesis of what environmentalists hold dear. Added to that is a cultural awakening, as here in Hawaii, that seeks to preserve historical or religious sites.Last is NIMBY, or Not In My Back Yard. Many staunch supporters of the armed forces object to nearby land being taken for military use, especially if it is valuable. In a classic case, more than a decade ago, the Pentagon sought to deploy new intercontinental ballistic missiles in Utah, a conservative, pro-military state. The NIMBY objections were so strong that the plan was abandoned.

In Hawaii, military commanders have an added concern, a privately expressed fear that if the Army concedes to Malama Makua's demand for a comprehensive environmental study, that will not be the end of it. Even if that study shows that training could be resumed without damage to the environment or to cultural and religious sites, they worry that something else will be brought up to stop their training.

David Henken, Malama Ma-kua's attorney, contends that his client's objective is limited to protecting the environment and cultural sites in Makua. He acknowledges, however, that some members of the association want to drive the Army completely out of the valley.

Longer range, the military services fear that Makua would not be the last target if the Army is driven out. They note that they have already lost access to Kahoolawe, the uninhabited island that was used for training and as a gunnery and bombing target. Kyle Kajihiro, the local representative of the American Friends Service Committee, which has supported Malama Makua, says the goal is to "end the U.S. military occupation of Makua Valley."

Kajihiro asserts that the ultimate objective is to "eliminate the presence of the U.S. military in Hawaii." If successful, that would remove one of the state's two main economic pillars, the other being the visitor industry. The Army alone provides 20,000 jobs and spends $1.4 billion in Hawaii each year.