Salt Lake City biotechnology company BioMicro Systems Inc. used last week's biotechnology meeting in Waikiki to unveil an invention it says could bring new, cheaper drugs to market in a shorter time, speed up genetic research and simplify medical testing procedures. High-tech

MAUI chip is

not for snackingSpecialized computer chip

Biotechspeak By Lyn Danninger

can analyze body fluids,

speeding research, diagnoses

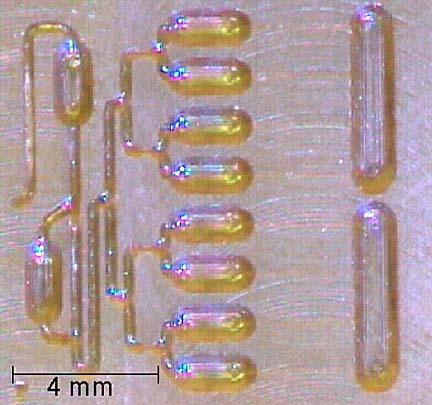

Star-BulletinThe new technology, unveiled at the Biotechnology Industry Organization's AsiaPacific 2001 conference, uses microchips as a platform to move tiny amounts of fluid that, in turn, analyze biological specimens.

The technology, referred to as micro fluid analysis, will initially be applied in pharmaceutical, genetic and other types of laboratory research. But eventually it could be used in hospitals and doctors' offices.

The type of microchip also has a Hawaii connection, if in name only. It is known as a Micro Array User Interface, or MAUI for short. It is used to prepare DNA samples.

For example, an unknown sample of DNA can be screened against a number of known samples to detect mutations. By identifying those, it is possible to predict a patient's response to a particular drug.Right now, such a study is possible, but it is both time- and labor-intensive as well as very expensive, said Michael McNeely, president and chief executive officer of BioMicro.

But by using BioMicro's micro fluid analysis technology, McNeely said, the process becomes a simplified, quicker and less costly way to screen a sample for its genetic composition.

The process is now cumbersome, either being done manually or using a bulky automated slide processing system that requires a large volume of costly chemicals, McNeely said.

Companies involved in research spend millions of dollars every year on these chemicals, known as reagents, needed to analyze various types of specimens. The new product requires smaller amounts of these chemicals.

"It's a way to minimize that cost and also reduce the volume of the reagents used," McNeely said.

The MAUI microchip also allows multiple samples of the same slide to be processed simultaneously, saving time.

Because the microchip is used in genetic screening, it means that in the future, drugs could be personalized based on a person's genetic make-up.

A federal study conducted about a year ago reported as many as 100,000 deaths occur every year from adverse drug reactions, said Bill Pagels, vice president of business development and marketing for BioMicro. Reducing those numbers is a possible benefit of the technology, he said.

The technology has already attracted the attention of some pharmaceutical companies, McNeely said.

Traditionally, the prevailing thinking in drug development has been that of one-size-fits-all, he said.

But by conducting a pharmacogenomic study -- an analysis of an individual's genetic make up -- it would be possible to see which drugs would work best for a person and which ones should be avoided because they may lead to a possible drug reaction.

Currently it can take $400 million to $500 million over 10 years to develop a new drug, McNeely said.

The new technology would allow pharmaceutical companies to develop drugs and bring them to market less expensively and more rapidly, he said.

The microchip technology also has the potential to significantly reduce costs associated with treatment of AIDS, McNeely said. Because the virus that causes AIDS has the ability to change very quickly, AIDS patients must be tested at least three to four times a year to see if the drug therapy they receive is on target or needs to be modified.

Currently, government health care plans such as Medicare only reimburse about $65 for the test -- not even enough to cover the cost of the reactive chemical agents used in the test, according to Pagels.

The cost of the tests could be substantially reduced for the 1 million to 1.5 million people in the United States infected with HIV, since the microchip technology requires a fraction of the chemicals normally needed, Pagels said.

With the new technology soon to go to market, McNeely and Pagels are hoping the Waikiki conference will result in attracting partners who will help in its manufacturing, marketing and distribution, particularly in Asia.

BioMicro was originally formed in 1997 to find ways to reduce operational costs and introduce new technologies for a company that specialized in genetic disease research screenings.

Last year, McNeely and his partners spun off the technology and attracted investors from Utah, Pittsburgh and Korea. The total investment so far for the technology is $4.5 million, with $1 million of that coming from Korea.

BioMicro is also looking for sites to test and validate studies of the product. Possible sites include the Cancer Research Institute of Hawaii and Pacific Biomedical Research Center at the University of Hawaii.

Dr. Suresh Patil, director of the biotechnology program at the center, met with McNeely and Pagels. Patil's laboratory supports molecular and genetics work done by researchers in both the public and private sector.

Based on what he has seen and heard so far, Patil said he is impressed with the BioMicro technology.

"The BioMicro product would enhance the effectiveness of the equipment we already have. Especially for large scale arrays, it allows you to improve the processing" he said.

Patil has agreed to test the device for BioMicro when it becomes available.

Ultimately if it works, Patil said he would favor purchasing the technology.

"If it really works and improves the whole system, we won't mind buying," he said. "Under certain circumstances, it could make us more efficient."

>> Micro fluid analysis circuit: It harnesses the natural forces that exist within fluids on a very small scale to control the fluid's movement through a circuit network on a microchip. Definitions

>> Assay: Technique for measuring a biological response.

>> Reagent: Substance used in chemical reaction.

>> Gene: A segment of chromosome. Some genes direct the syntheses of proteins while others have regulatory functions.

>> DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid. The molecule that carries the genetic information for most living systems.