Cruise industry MIAMI >> Drive over the Port of Miami causeway: The asphalt arches above the gray-green water licking gently at busy tugboats, small pleasure craft and enormous cruise ships that berth in one terminal after another. More cruise ships call this port home than any other.

struggles

Hawaii, Alaska and Florida

look at ways to control pollution

in the face of growing cruise

ship trafficBy Sharon L. Crenson

Associated PressAnd they leak more oil and dump more garbage off Florida's shores than anywhere else in America.

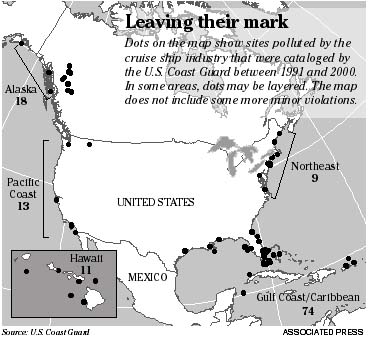

U.S. Coast Guard data indicates cruise ships polluted Florida waters at least 60 times over the last nine years, according to a computer-assisted analysis of marine pollution records. Alaska, the runner-up, had 26 spill reports.

The Associated Press compiled the numbers by crossing a list of 238 cruise ship identification numbers with a Coast Guard database that included both proven and alleged pollution incidents. The comparison showed cruise ships were suspected of causing 172 spills from 1991 through Dec. 31, 2000.

That represents a small fraction of the 194,075 cases recorded for all marine polluters, but some cruise ship examples are noteworthy:

>> 16,000 pounds of garbage dumped by a ship called the Ecstasy in 1992.

>> 2,000 gallons of fuel oil by the Oceanic in 1993.

>> 200 gallons of oil by The Big Red Boat II in 1997.

The records show oil, hydraulic fluid, plastic and other cruise ship pollutants wind up in U.S. waterways. Often small amounts of paint, food and chemicals also foul the seas.

Click the image to see a very large version.

The Hawaii state Office of Planning is looking into the environmental affects of Hawaii's burgeoning cruise ship traffic."The state of Hawaii is sort of in a scoping stage," said Gary Gill, deputy director of the state Department of Health.

The planning department is holding agency meetings designed to identify the concerns of various state departments, said Chris Chung, program coordinator for the Coastal Zone Management division, which is overseeing the effort. His office is considering meeting with industry officials, but no dates have been set.

And Gill's staff is doing research that includes looking at the approach taken in places like Alaska.

"Health Department concerns deal with solid waste and clean water issues," said Gill. Another issue is the unloading of garbage at ports of call, which can particularly task rural areas, like the neighbor islands, that already have limited landfill space, he said.

Some dirtier than others

The Texas Treasure, a gambling boat that sails the Gulf of Mexico, was cited more than any other cruise vessel -- nine times in nine years. The Oceanic, a 1,100-passenger ship formerly run by Premiere Cruise Line, was cited five times; and the Britanis, an aging vessel that has since been retired, was also cited five times.Not quite one-third of the fleet -- 68 cruise ships -- were responsible for the bulk of the problem.

Most of the cases are minor and accidental, says Michael Crye, president of the International Council of Cruise Lines, which represents the $15.5 billion cruise industry. Overall, the industry is performing well, he said, when compared to other maritime and land-based polluters.

Indeed, the AP analysis showed tugboats, fishing vessels and passenger craft other than cruise ships were responsible for far more pollution.

Still, the cruise line problems have made their parent companies targets for environmentally friendly lawmakers and lobbyists since 1999. That's when the U.S. Justice Department settled the second of two multimillion-dollar cases against Royal Caribbean Cruises, a company that admitted polluting repeatedly and lying to the Coast Guard about it.

Subsequent inquiries by the U.S. General Accounting Office, the Environmental Protection Agency and Alaska's Department of Environmental Conservation have forced cruise companies into a legal and public relations war that threatens to tarnish their "Love Boat" image.

Hawaii state Rep. Blake Oshiro introduced a bill to prohibit cruise ship dumping this session and co-sponsored a resolution to study the environmental consequences of the industry. Both measures are dead."I'm really concerned about this unregulated waste dumping that goes on, especially as we see that the cruise industry is a growing industry here," he said.

Heavy opposition to the anti-dumping bill prompted the call for a study, which Oshiro plans to revive next year.

"People are very wary of accepting progressive measures and studies are usually needed to back them up," he said.

"One of the main problems is the shipping industry is not really open to having themselves regulated," said Oshiro. A bill proposing regulations to clamp down on alien aquatic organisms brought to Hawaii on the hulls of boats and in bilge water also met strong opposition from the shipping industry. That measure was turned into task force, said Oshiro, giving him hope the same could happen with the dumping issue.

Clamp down

Step aboard the Grand Princess in Fort Lauderdale on any given Sunday and fantasy comes alive. It's picture-perfect from the blue sea-witch logo atop the smokestacks, right down to the captain's white shoes.Rain? A dome encases the swimming pool. Glass elevators whisk you from one deck to the next. Everywhere, smiling, blue-blazered greeters stand ready to assist.

Hours before setting sail for the eastern Caribbean, guests wander to Horizon Court, a 24-hour eatery, to fill their plates with sliced cantaloupe, fried scallops and pineapple.

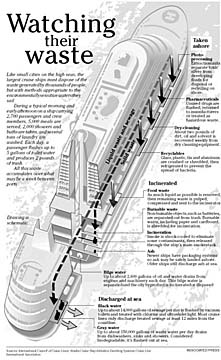

But what happens to all those leftovers? And what about the sewage produced by 2,600 passengers and 1,100 crew?

A decade ago, no one thought about it.

Then, on Oct. 25, 1994, a Coast Guard jet over the Atlantic spotted an oil slick shimmering behind what was then the world's largest cruise ship -- Royal Caribbean's Sovereign of the Seas.

Inspectors boarded her in San Juan harbor, but ship officers denied discharging anything. Still, the fuse of suspicion had been lit. Over the next four years, federal investigators discovered Royal Caribbean engineers routinely bypassed pollution controls to dump oily waste into the sea.

Sometimes, according to prosecutors, crew members falsified records in what they called their "fairy-tale books."

It was supposed to save the company money. It wound up costing $18 million in fines."The industry certainly did some things -- and Royal Caribbean particularly did some things -- that certainly were not right," says Nancy Wheatley, Royal Caribbean's senior vice president for safety and the environment.

But that was long ago, she said.

Today, Royal Caribbean distributes an environmental report that touts "a vacation resort, complete with infrastructure." A tidy blue and green graphic shows how the bones from meat, the shells from seafood, the glass from beer bottles get recycled or incinerated for disposal on land.

Princess supplies cardboard shampoo and lotion bottles rather than plastic ones, and offers guests the option of reusing towels.

"It's a different business than the seagoing voyages of old," says Tom Dow, vice president of public affairs for Princess.

Even the Coast Guard recognizes a cruise company turnaround.

"They have been very proactive in trying to take care of pollution issues," says Rajiv Khandpur, a civilian program manager with the Guard's Office of Compliance. "They're not proactive just because they're good guys, but because it does affect their business."

Lobbyists and some lawmakers -- including some who made headlines criticizing cruise companies -- remain unconvinced.

Bluewater Network, a San Franscisco-based environmental group, is pressing EPA to tighten industry regulations. California has authorized a new task force to track wastewater spills.

And in Florida, the same U.S. Attorney's office that helped prosecute Royal Caribbean has turned its attention to NCL Holdings, the parent company of Norwegian Cruise Line; and to Carnival Corp., the world's largest cruise company.

Neither business would comment, citing an ongoing grand jury investigation. However, Norwegian general counsel Robert Kritzman said his company went to federal authorities voluntarily after an internal review revealed "a pattern of violations of environmental law."

Alaska investigates

From her office window overlooking Juneau Harbor, Michele Brown surveys a slice of what could be Alaska's third largest city -- not Juneau itself, but a cruise-ship fleet. The industry brought 640,000 travelers to Alaska last year, compared to 200,000 a decade ago.As the state's environmental conservation chief, Brown says she always worried about the effect such massive vessels had on water teeming with salmon, halibut and Dungeness crab.

Last summer, her fears deepened.

Spurred by the Royal Caribbean investigation, Brown and Alaska Gov. Tony Knowles persuaded cruise officials to test smokestack emissions and water discharges along the Inside Passage, a waterway winding around scores of islands west and south of Juneau.

Of 80 water samples taken from ship storage tanks, only one met federal standards for suspended solids and fecal coliform, a bacteria found in human feces, which can build up in shellfish. Some of the samples contained more than 50,000 times the bacteria federal law allows in treated sewage. Normally, that water is expelled into the ocean.

The results left Knowles spoiling for a fight.

During a September news conference, the governor demanded to know whether industry executives had realized their floating cities routinely fouled the delicate archipelago.

Had company officials lied when they told state regulators their discharges were clean? Or had they simply not checked?

The test results showed cruise ships had also dumped chemicals and traces of heavy metals into Alaska's icy blue waters. They raised questions about both the adequacy of shipboard sewage treatment systems, and the relative purity of so-called "gray water" drained from showers, sinks and galley clean-up areas.

Gray water is usually discharged into the ocean without treatment. Vessels large and small are allowed to expel the soapy liquid even within the three-mile shore zone where federal law prohibits other discharges.

Those other discharges concern Gill at the Hawaii state Health Department.

"The treatment of human sewage on a ship is minimal and federal law allows the flushing of wastewater anywhere three miles off shore. Three miles off shore is between Maui and Lanai," he said.

But jurisdiction over the matter belongs to the Coast Guard and the state's regulatory options are unclear, said Gill.

Some companies, like Royal Caribbean, voluntarily refrain from releasing waste water within 12 miles of shore, in part because large cruise ships produce so much of it -- up to 1 million gallons per week.

Alaska's Brown says the fecal coliform levels now known to be associated with cruise ships may be a "serious pollution load, depending on how it's handled."

As a result, Congress passed a law prohibiting cruise ships from discharging treated sewage within a mile of any Alaskan port. It also allows the state to set interim purity standards for gray water.

Dow, the communications director for Princess, said his company and other cruise lines are looking to upgrade their water treatment systems.

But Kira Schmidt, a spokeswoman for Bluewater Network, said such self-policing is no substitute for federal or state oversight.

She dismissed cruise lines' efforts to "make it look like they are clean and green. I'm concerned that it's a PR maneuver and that it's pretty superficial."

Little new action

Compared to Alaska, Florida has seen little environmental activism over cruise ships. Even groups like the Sierra Club are concentrating more on saving the Everglades than the ocean.Although some of the same cruise ships polluting Alaska last summer made their way down the coast and through the Panama Canal to Florida piers this winter, Florida regulators have not made demands of cruise executives that Alaskans have.

Instead, the state signed a memo of understanding with the industry, which states that cruise companies will comply with environmental laws and cooperate with regulators.

The International Council of Cruise Lines, the Florida Caribbean Cruise Association and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection labored over the document for a year before settling on its eight key points. The main one underscores the environmental department's acceptance of the cruise industry's existing waste handling practices.

When the AP first inquired about the memo, a spokeswoman in Gov. Jeb Bush's Department of Environmental Protection referred questions to the FCCA, the industry trade group.

Another administration spokesman later said the state opted for the memo rather than legislation so that the Coast Guard could step up its industry monitoring sooner.

Hawaii Health Department's Gill also said voluntary initiatives may be the answer.

Cruise companies rely on the hospitality of ports of call, so they are likely to want to comply, he said.

Star-Bulletin Business Editor Stephanie Kendrick contributed to this report.