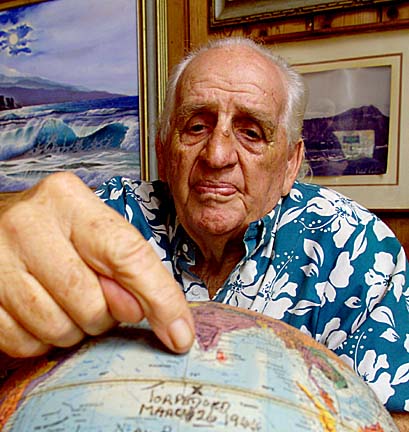

Can of fruit Each year on March 29, James Blears wakes up and opens a can of peaches. The annual breakfast ritual reminds him of the preciousness of life and the importance of never giving up, which may have had something to do with his success as the professional wrestler and promoter known as Lord "Tally-Ho" Blears.

symbolizes

survival

A meal of peaches serves as

By John Berger

a reminder of life's sweetness

Star-BulletinA can of peaches was the first food he received after he was rescued in the middle of the Indian Ocean several days after the Tjisalak, a Dutch merchant ship, was sunk by a Japanese submarine in the waning days of World War II. Almost all of the ship's 77 crewmen and 27 passengers survived the sinking and were taken aboard the I-8 submarine on March 26, 1944.

Blears, a 21-year-old radio officer, was one of five men who escaped the slaughter that followed as Japanese officers took the lead in killing prisoners.

"They were laughing," Blears recalls 57 years later. "They'd just go up and hit a guy on the back and take him up front, and then one of the guys with a sword would cut off his head. Zhunk! One guy, they cut his head halfway and let him flop around on the deck. The others I saw, they just lopped 'em off with one shot and threw 'em overboard. They were having fun, and there was a cameraman taking movies of the whole thing!"

The Japanese shot or decapitated many men on the foredeck. They tied others in pairs and marched them behind the conning tower. Screams and gunshots followed.

Blears realized his turn would come. The time he spent waiting seemed like an eternity. Four years of wartime service in the merchant marine, and his life was over.

He had been too young at 17 to enter the Royal Navy, but the merchant marine needed radio officers, and Blears' knowledge of Morse code helped him wrangle his way in. He then risked his career by turning down a backwater assignment that would have kept him out of harm's way. Instead, he took a posting to the Tjisalak because the Dutch vessel needed an English radio officer.

Two torpedoes from the I-8 slammed into the Tjisalak just before dawn that day in March. The I-8 crew ordered the survivors to row lifeboats to the submarine. Senior officers and the Tjisalak's only female passenger were taken into the sub. The others squatted on the deck as the I-8 got underway.

The killing started shortly afterward.

Blears was hit with the flat of a sword and dragged to his feet. A Japanese sailor tied his wrists behind him, then tied him to one of the other men.

"You'd hear them laughing and then bang-bang-bang -- pistol shots -- and rat-a-tat-a-tat-a-tat. ... I tried to keep my wrists as wide apart as I could when they tied me, and when they were finished I knew I could get one hand free.

"Two Japanese officers were waiting for us, one with a sword and the other with a sledgehammer. ... When these guys came at us, I kicked with my foot and pulled my hand out (of the rope) right away and stopped the guy and dived off the submarine and dragged Peter (Bronger) with me."

Blears went as deep as he could while bullets stabbed the water.

"I stayed under as long as I could, and then I came up with my head just out of the water and -- tat-tat-tat-tat -- machine gun bullets were going all around. When I came up for my next breath, the submarine was quite a way away. ... There were two officers in old-fashioned deck chairs firing with rifles. I kept diving until I saw that they weren't firing at us anymore."

By that time Bronger was dead, (Blears suspects he was killed by a sword blow.) and Blears' only chance for survival was to swim back to the ship, Tjisalak. Maybe one of the lifeboats would be intact. Maybe there would be some food, water or a radio. It was swim or die. Blears swam.

He had been a championship swimmer in school and was training for a spot on the English Olympic swim team when war pre-empted the 1940 games. He found wrestling was a great way to get in shape and finance his training. Blears supplemented his merchant marine salary by wrestling whenever he had a few days in port. A professional wrestler could earn 5 pounds a match, while a skilled laborer was doing well to earn 3 pounds a week.

Blears swam all that day. He began to lose hope as the day ended, but luck was with him. He was able to rest for a while on a card table in the wreckage, then saw a life raft and heard someone yell. There were sharks in the area, but Blears "swam like I was breaking the world's record" and found the first of four other survivors.

Three of the Dutch officers had experiences similar to Blears. The other man, an Indian seaman, Dhange, had been one of about 20 men who had been tied to a long rope attached to the conning tower. The sub had then submerged. Dhange, at the far end of the rope, managed to free himself.

Blears and the others salvaged what they could from other rafts and lifeboats and attempted to set course for Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), more than 500 miles away. One of the officers was seriously wounded.

The men thought help was at hand when they spotted a ship in the distance. Then the ship began firing at them, and they realized it must be a Japanese raider.

They were about to jump overboard when the shooting stopped. The crew of the S.S. James A. Wilder had mistaken the lifeboat's sail for a submarine's conning tower.

And the sailors gave Blears a can of peaches.

After the war, two officers of the I-8 were convicted of war crimes and served five years for their part in killing the crew and passengers of the Tjisalak.

The English government announced last year that it would pay 10,000 pounds (roughly $15,000) to all English military personnel, civilians and merchant marine sailors who were prisoners of the Japanese. Blears was only a prisoner for an hour or two, but they were the longest hours of his life -- and almost his last. He is awaiting word on the status of his claim.

Blears would like to see all ex-prisoners receive a comparable payment from the Japanese government -- or at least an official apology -- but he is not optimistic about receiving either. In the meantime he opens a can of peaches each year to celebrate his survival and to remember those who perished.

Click for online

calendars and events.