Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

By Helen Altonn

Star-Bulletin

THE enforcement officer had trouble stifling a laugh when the man told him he didn't have a placard, but was entitled to park in a reserved disabled space because of his passenger.

"Look in the back seat of my car -- my dog's handicapped," he told the officer, William Stirling.

"In 18 months now, that's the best one I ever heard," said Stirling, one of 19 voluntary disabled-parking enforcement officers commissioned by the Honolulu Police Department.

"Back in the van, my partner and I laughed our heads off."

But violations of the disabled-parking law aren't a laughing matter to the volunteer officers, HPD or state Disability and Communication Access Board.

They're seeking tougher penalties for violators -- including doctors -- and other changes for better enforcement of the law.

Stirling was assaulted in February 2000 by a man who became belligerent after being cited. The offender was convicted and sentenced this month to six months probation and a $75 fine -- not nearly enough, said Stirling.

"There is a looseness (in the law) we hope to address with higher penalties," said Francine Wai, executive director of the disability board.The program was transferred to her office in July from the state Transportation Department. "We realize somebody who really has a vested interest in it and cares about it has to do it or it will flounder," Wai said.

Honolulu Police Sgt. Bart A. Canada, who works with the volunteer enforcement officers in the Special Field Operations Bureau, has a special interest in enforcing the law because of his own experience and a large volume of complaints -- more than 4,000 calls last year on Oahu.

"We don't have staff to keep up," he said.

Canada was injured in an accident in 1996 when he was a solo motorcycle officer. With his leg in a cast, he needed disabled-parking space to swing the door open to get out of a car.

"One cannot truly appreciate the program until they are disabled themselves or have a family member disabled," he said.

Enforcement officers see a lot of fraud -- from photostatic copies made to look like real ones to people parking in disabled stalls at golf courses and walking away carrying golf bags.

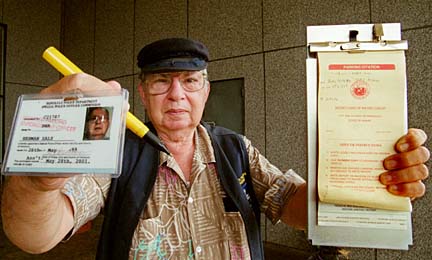

Herman Salz, who helped form the civilian patrol, and his partner cited a golfer with an altered placard at the Ala Wai Golf Course.

"He was wearing his golf shorts and shoes, waving his placard at us, ticket in hand. We told him it had expired five years ago.

"He said, 'Come to think of it, my wife died five years ago and it's her placard,' " Salz said.

Placard recipients are issued ID cards, which they must carry to prove the placard belongs to them. The county discontinued photos on the cards as too costly, although Wai and the officers are urging that photos be required.

Excuses, excuses

A big problem is that legitimately disabled people often don't display their placards on the rearview mirror or dashboard as required by law, and they don't feel they should be asked for identification, the officers said.Meanwhile, people who park illegally in handicap spaces have a variety of excuses:

"I was in the store for only a minute."

"I just went to the mailbox."

"The person who has the placard is in the store" (when there's nobody).

"My mother died and put it in her will that I should have the placard."

A young person will say he left his placard at home and it's really his father's, Stirling said. "Dad goes to the courthouse and gets it dismissed. The courts are very lenient."

George Fox, a voluntary enforcement officer who is also with Advocates for Consumer Rights, said his wife was in Queen's Medical Center for three days about four years ago. Each day, two vehicles parked in disabled stalls with counterfeit IDs on the dashboard and no placards, he said.

He became even more aware of the abuses after receiving a placard three years ago because of circulation problems in his legs.

"Far too many drivers who do not meet the requirements have placards," he said. Other problems, he said, are improper signage at the parking spaces, improper or nonexistent access aisles and inadequate fines.Many times, when the officers seize placards, those cited say, "Oh well, I'll just go to my doctor and get another one," Stirling said.

They also get replacements readily at satellite city halls. Salz tells of one man who got five placards in one week and was selling them for $100 each.

Placards aren't transferable, yet that's done constantly.

"People leave a placard in the car and a nephew, niece or uncle is using it," Stirling said.

Salz recalled the case of a woman driving her husband's car at Kahala Mall. She had two placards, one expired and one new, and no identification.

He had to call for police backup when she insisted on paying the ticket and keeping the placard. "She got the ticket she asked for but we sent the placard back. It was evidence."

Program needs funding

Legislative funding is being sought to operate the disabled-parking program in Wai's office, for the HPD civilian patrol and for the counties.The state formerly purchased the placards, with the counties reimbursing the state from placard fees varying from $6 to $10.

That changed about two years ago as courts ruled the fee for a disabled-parking placard was considered a surcharge under the American Disabilities Act. The 9th Circuit Court ruled the fee was illegal in two cases early last year.

Revenue from citations goes into the state general fund, so the counties receive no funding to pay for the placards or operational costs, said Dennis Kamimura, administrator of the city Motor Vehicle and Licensing Division.

With the cost of issuing the placards in Honolulu estimated at more than $100,000, Kamimura said, "Right now, we're eating it."

His division estimated there are about 40,000 to 60,000 placards on Oahu, but exact figures aren't known because computerization of the program has just begun.

Wai proposes setting up a statewide data base, pointing out, "There is no way you can enforce without a good record-keeping system."

HPD began the citizen patrol program in November 1996. The program began as a pilot project under the city administration and later was transferred by law to the state.

Word went out and volunteers began showing up for training. After initial problems, "It's going fantastic," Salz said.

Although the volunteer officers encounter a lot of verbal abuse and occasional confrontations, about 95 percent of handicapped people are pleasant and grateful for the enforcement, Stirling said.

"Maybe we have five percent or less that think because they're disabled they don't have to show identification," he said.

People may apply to use reserved parking spaces if they have a disability that limits or impairs their ability to walk, with a medical statement from a licensed physician verifying the condition. Disabled-parking system process

A temporary red placard may be issued for up to six months and renewed for six-month periods. A permanent blue placard may be issued for up to four years, then renewed another four years. There is no charge for the placards.

A special license plate may be issued for four years for a disabled person's primary vehicle, as well as a placard for use if riding in another vehicle. The license plate costs $5.50.

Placards must be displayed from the rearview mirror or on the dashboard.

People with parking placards or special license plates must have an identification card stating the placards or licenses were issued to them.

Source: Hawaii Revised Statutes, Chapter 291-51 to 291-56.

Bills pending in the state Legislature propose: Disabled-parking bills at Legislature

Increased penalties for violations at disabled-parking spaces ranging from $250 to $500. The range now is $155 (including a $5 fee) to $300

Imposing fines up to $1,000 and/or up to 30 days in prison for doctors who fraudulently verify that a person is disabled

Providing similar fines for fraudulent manufacture or alteration of placards and identification cards or their use

Including people with renal and oncological conditions in the "disabled person" definition for obtaining a handicapped parking placard

Allowing the counties to charge fees to replace lost or stolen identification cards. The fee would be waived for a stolen card upon presentation of a police report

Requiring a new application and disability certificate upon renewal of a parking placard and prohibiting anyone from having more than two at one time