Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

State: Big oil The major oil companies in Hawaii tried to cripple Aloha Petroleum in the 1990s because its lower gas prices undermined a scheme that produced high profits for the industry and high costs for consumers, the state alleges in court documents.

firms tried to cripple

Aloha Petroleum

Attorneys for several firms

dispute the allegations that

they conspired against

Aloha's lower pricesBy Rob Perez

Star-BulletinAloha's pricing strategy prompted the other companies to boycott Aloha until it started importing gasoline, the state says in documents filed as part of a $2 billion antitrust lawsuit against the major companies. Aloha began importing in 1997.

Attorneys for several of the oil companies strongly denied the state's allegations.

"That's just nonsense," said Alan Grimaldi, a Washington, D.C., attorney representing Texaco Inc. "There's absolutely no evidence of that."

In fact, Texaco sold gas to Aloha for distribution on Maui and partnered with the local company in the mid-1990s to expand a Texaco fuel storage complex at Barbers Point, Grimaldi said. The new terminal, which was completed in 1997, was jointly owned by the two companies until Texaco sold its Oahu assets in early 1999.

"How could we be accused of crippling them" when they built the terminal together, Grimaldi asked.

Attorney John Myrdal, who represents Unocal Corp., likewise dismissed the state's allegations. "These are totally false," he said.

Myrdal noted that Unocal leased terminal space to Aloha before the Texaco-Aloha facility was completed.

Had 20-year contract

Aloha also had a 20-year supply contract with BHP Petroleum, which used to own one of Oahu's two refineries, until 1997, Grimaldi said.Few details of the state's allegations have been made public, and Spencer Hosie, the San Francisco attorney heading the state's case, did not respond to requests for comment. Aloha Petroleum also did not return phone calls seeking comment.

The allegations are briefly mentioned in an October 2000 federal court filing by Texaco, a defendant in the antitrust case.

One state document referred to in the Texaco filing said Unocal, also known as Union Oil, refused in 1993 to provide Aloha with fuel that could be obtained directly from Unocal's suppliers. Unocal at the time got its supply from BHP and Chevron, which owned the other Oahu refinery, in exchange for providing gas to the two companies elsewhere.

Unocal refused for the next two years to provide fuel or "terminaling" to Aloha, according to the state.

"This refusal confirms that Union had joined with its 'exchange partners' to control and cripple Aloha as a price competitor in the Hawaii market," the document said.

Chevron did not respond

A Chevron spokesman did not respond to a request for comment. A spokesman for Australia-based BHP, which sold its Hawaii refinery and gas stations to Tesoro Petroleum Corp. in 1998 and no longer is in the market, could not be reached for comment.In the court document, the state said Unocal considered Aloha to be a price cutter whose marketplace conduct reduced profit margins for Unocal and its exchange partners.

The state then quoted from a 1995 Unocal memo to support its contention.

"Aloha is a fast growing independent competitor generally not looked upon favorably by our competitors or Unocal dealers and marketers because of their price cutting actions at retail and wholesale," the March 1995 Unocal document said.

Little additional information about the alleged effort to gang up on Aloha is found in the public portion of the lawsuit file. Most details are in documents still under seal and unavailable for public inspection.

But in a 1994 report on Hawaii's high gas prices, the state attorney general's office said Aloha claimed it could not obtain competitive exchange agreements with Chevron and BHP.

Yet the other companies that did not make gasoline here had exchange agreements with the two refinery operators.

The exchange agreements, the state alleges in the lawsuit, were only available to companies that would not compete on price, preserving high profit margins. Those agreements were used to allocate market share among the companies and to fix prices, according to the state.

Tim Hamilton, a mainland petroleum analyst who has studied Hawaii's market, said he wasn't surprised by the state's allegations.

'Common business practice'

In mainland markets where independent gas marketers aggressively cut prices to try to build volume, the major oil companies pressured the independents to retreat or face being driven out of business, Hamilton said."This has been found and shown and documented before," he said. "It's a common business practice."

Hamilton said Aloha likely was pressured into keeping its per-gallon prices within a few cents of the stations run by the oil companies. That way, Hamilton said, Aloha could not continue taking market share from the other companies.

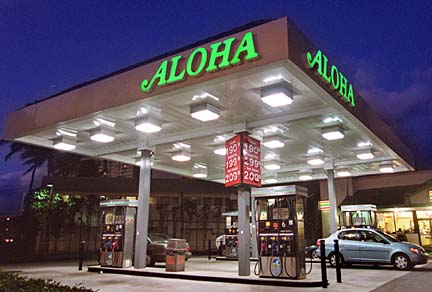

Dealers at competing gas stations say Aloha, an $80 million company with roughly 15 percent of the Oahu market, does not price as aggressively today as it did in the early 1990s. Aloha stations, which are operated by the company instead of dealers, generally are in the low end of the price range on Oahu.

When the state filed its antitrust lawsuit in October 1998, Aloha was the only major gas company in Hawaii that was not named as a defendant.

Hosie at the time said Aloha was excluded because it initially wasn't part of the group that conspired to keep Hawaii prices artificially high.

When Aloha bought gas locally, it was charged a higher price than the other major suppliers that got fuel from Hawaii's refiners, Hosie said.

Once Aloha started importing less-expensive gas, however, it did not pass on the savings to consumers and benefited from the alleged conspiracy, Hosie said in the October 1998 interview. The oil companies have denied the conspiracy charge. The lawsuit is scheduled to go to trial in September.