Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Epileptic Maui WAILUKU -- Maui police Chief Thomas M. Phillips was attending a conference in Washington, D.C., when he saw a man fall into an epileptic seizure.

man has a desire

to educate

The Epileptic Foundation has held

seminars with many groups, including

police and fire departmentsBy Gary Kubota

Star-Bulletin"We were able to care for the man until the medics arrived, despite others in the crowd giving the wrong advice such as, 'Put something in his mouth,' 'Roll him on his back,' 'Try to hold him down,'" Phillips recalled.

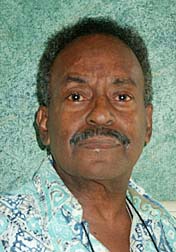

Phillips said he gained his first-aid knowledge through Maui resident Glenn Mabson, president of the Epileptic Foundation of Maui.

The nonprofit foundation has been operating out of Mabson's house in Kihei and is looking for office space.

Three years ago, Mabson, with the help of his mother, Ozella, started the foundation on the Valley Isle, and has since conducted seminars with various groups, including the police and fire departments.

Mabson, who has epileptic seizures himself, said most people do not realize the number of residents who have epilepsy.

Mabson said he has heard of people on Maui with epilepsy dying from what appeared to be epileptic incidents. He thinks education in first-aid care could improve things.According to the Epilepsy Foundation of America, more than 2 million people, or close to 1 percent of the population in the United States, have some form of epilepsy.

About 30 percent are children under the age of 18.

Mabson said he does not have statistics but believes the percentages are higher on Maui, based on his talks with physicians and teachers.

Epilepsy is a general term for more than 20 types of seizure disorders caused by brief changes in the normal function of the brain's electrical system.

The condition most commonly associated with epilepsy is generalized tonic clonic, or grand mal.

The symptoms of grand mal may have the person crying out, falling, and having muscle spasms and a lapse of consciousness.

Experts say persons having a seizure should be allowed to remain where they are unless they are in danger of hurting themselves.

The person will usually come out of the seizure in a few minutes.

Less noticeable are partial seizures, which blur awareness and distort sensations, a condition often mistaken for drug or alcohol abuse.

There are also absence or petit mal seizures, found more commonly in children between ages 4 and 8 years old, predominantly among girls.

Experts say a child could have more than 100 petit mal seizures a day.

Petit mal seizures could cause children to stare blankly into space for a few seconds. They may blink their eyes rapidly or make chewing movements with their mouths.

Dr. Nancy Greenwell, a family practitioner, said without knowing the symptoms, teachers may think the child is daydreaming.

"I think the major danger is that they're going to lose out and may be branded as a child not paying attention," Greenwell said.

Greenwell said because the condition is out of the child's control, he or she may become frustrated and develop a learning disability.

Mabson himself has experienced the frustration of people not understanding epilepsy. Four years ago, he had a grand mal while on a walk in South Maui.

He said his seizures are caused by injuries he received as a CBS technician covering the war in South Vietnam and as a prisoner of war from 1969 to 1971.

Mabson said police who arrived at the scene thought he was drunk or on drugs and handcuffed him and put him in the back seat of their car.

Mabson said he came out of the seizure en route to the police station and could not understand the reason for his arrest.

Police confiscated his medication, and Mabson stayed in jail for about four days while continuing to have seizures.

Mabson said that when he got out he thought of suing the police, but he realized it was more important to direct his energy toward promoting epilepsy awareness.

"I could not find it in my heart to blame the police for what had happened. They just didn't know," he said.

Mabson said he and his mother put up their own money to start the nonprofit, tax-exempt Epileptic Foundation of Maui.

Mabson said the police have been extremely cooperative and now require police recruits to undergo first-aid training for epilepsy.

The Foundation has received donations from various groups, including the McInerny Foundation and Pacific Century Trust.