Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

By Cynthia Oi When you talk with anyone who remembers the streetcars that once trundled through Honolulu, most of them will use the word "fun."

Star-BulletinThat's exactly what MacKinnon Simpson and John Brizdle say about the work on their book, "Streetcar Days in Honolulu."

Actually, Simpson will say more. "It was magical."

The two men have packed history, economics, sociology and technology into "Streetcar Days," detailing how the machines changed the landscape of Honolulu, the way business was conducted, the jobs and lives of people, and the interaction among them.

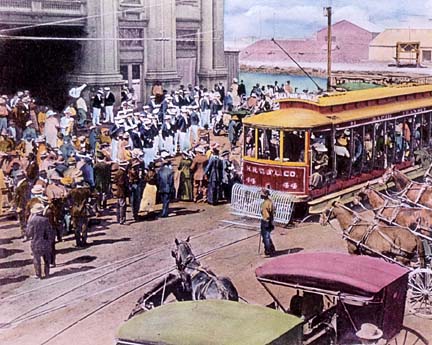

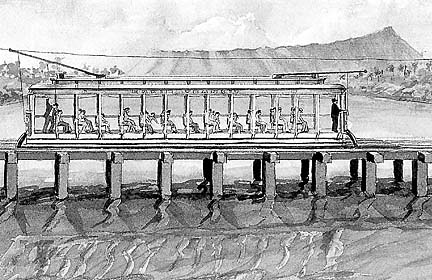

The visuals include documents, postcards, paintings, advertising plates, street signs and maps. Hundreds of photographs, some artfully hand-tinted, display a Honolulu from 1901 through mid-century, populated by mulecars, streetcars, trams and trolleys.One rare photo shows an open-sided vehicle rounding a curve of track that climbed Pacific Heights before homes were built on the slopes. The streetcar was part of the Pacific Heights Electric Railway, the first system in Honolulu.

Finding the photograph was just one of the "magical" moments that Brizdle and Simpson experienced while researching the book.

"We knew that there had been a thing that was called the Pacific Heights Electric Railway," said Brizdle. At a collector's sale, he came upon a "tiny little book" called "Guide to Honolulu 1901," essentially a tourist publication. Inside was the photo. "It was only 2 inches square. It was a real gem," said Brizdle.

The railway was owned by C.S. Desky, an entrepreneur and real estate developer who built the Progress Building, which still stands at Fort Street and Beretania. In the late 1890s, the book reports, Desky envisioned homes and a hotel on Pacific Heights, but realized that the land would sell better if there was a way to travel up and down the ridge. In November 1900, the first car climbed the hill and the ride, at 5 cents one way, became popular among sightseers. Unfortunately for Desky, few were willing to buy house lots and he was soon bankrupt.

Desky's failure aside, the streetcar allowed people to live away from central Honolulu.

"In those days -- there were only four automobiles on Oahu in 1901 -- you lived downtown because you worked downtown," Simpson said. "You couldn't live in Kaimuki or in Manoa."

"Unlike today, when we build a community, we send out a bus to service the people, but in those days they'd put a streetcar out there with nobody there. It was one of those 'if you build it, they will come' things."

The streetcars "created neighborhoods," he said. "People could suddenly live elsewhere and find a way into town."

Maps of Honolulu in 1897 show few byways outside the central city. "There were just a few little farm roads," Brizdle said. "Yet in 1900-1901, Manoa, McCully and Kaimuki are all laid out with grids and it's definitely because of the streetcars."

By 1904, the streetcars were averaging 18,327 riders a day, 365 days a year.

The streetcars not only opened neighborhoods, they sparked enterprises as transit lines created trackside attractions to lure riders. Honolulu Rapid Transit & Line Co., with donated money, constructed the Waikiki Aquarium, an immediate hit.

Brizdle and Simpson stumbled into the idea of their book.

Brizdle had worked with E Noa tours, the company that introduced the Waikiki Trolley. To give historic value to the tours, he put up copies of old photos showing various island landmarks in the new trolleys.

Then when he'd mention streetcars, especially to older people, "all these stories started coming out. Every time I'd talk to seniors they had funny stories about riding them, living along the line, the conductors."

He approached Simpson, a historian who worked with the Maritime Center and whom he had known since the mid-1980s when both coached soccer. Simpson has written nine other books, but was busy with other projects until last December.

"I told John, if we're going to do it, this would be a good time, and then the fun began," Simpson said.

Brizdle initially thought research would be boring, Simpson said. "It turned out to be really fun because we'd keep turning up more and more things, pictures people probably hadn't looked at in 100 years, and one thing after another, little clues led to big discoveries," he said.

Soon, his partner became caught up in it.

"The research was won-der-ful," Brizdle said, stretching out the word. "And the best part was the people stories."

The most common tale, at least among men, was about riding the streetcars without paying the fare.

"The men all claimed that when they were little boys, they'd ride for free -- jump on the streetcar and jump off when the conductor came over," Simpson laughed.

"Oh, yeah," said Brizdle. "It was like no man ever paid for a ride."

Even in those days, people wanted to get from one place to another quickly. So when HRT&L's electric cars ran a new Waikiki route in 28 minutes, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser headline shouted: "From Fort Street to Diamond Head in Less Than Thirty Minutes' Time."

Simpson laughed when he heard the suggestion that a half hour would be record time in today's rush hour. But neither he nor Brizdle believe streetcars are the answer to Honolulu's traffic problems.

The reason streetcars worked in the past was because of "economics and benefit," Brizdle said. "A nickel for a ride was a lot then, but it was affordable." As far as benefit, it was easier to leave your horse at home and catch the streetcar.

People today aren't willing to leave their cars behind and rapid-transit systems are so expensive.

While the book is full of technical and historic details about streetcars, Simpson said, that is not its primary focus.

"The title is 'Streetcar Days' and the 'Days' is important because it's really about people and the community, rather than the minutiae about rivets and car numbers. We were really more interested in the stories," he said.

"It is dedicated to the seniors, because we collected those stories from them who lived in '20s and the '30s. And it's time to collect those; they aren't going to be around forever," he said.

"What we're hoping is that this book will trigger an inter-generational discussion, that when people see it, they'll talk to their families about what it was like and how much fun they had riding the streetcar.

"And it was fun -- to ride this giant, noisy, clunking, clanging, rattling machine.

"Everybody had a sense of fun about them -- people who rode them, people who drove them. It was fun."

Click for online

calendars and events.