Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

LIHUE -- Leaders of Kauai's tourism industry and the island's environmental groups rarely agree on any issue. But they're practically hugging each other on this one: Both believe the state Department of Land and Natural Resources has allowed its facilities to fall into so much disrepair that they are being overwhelmed by visitors to Kauai.The result, both groups say, is needless damage both to the beauty of the island and the mood of the tourists.

How to do it right

Fund-raising ideasBy Anthony Sommer

Kauai correspondentBoth groups haul out identical lists of complaints:

DLNR officials don't deny it. In fact, they openly agree. But despite years of complaints, they haven't come up with a way to fix the problems.Crumbling and padlocked public bathrooms.

Hiking trails that are washed out.

Roads that are impassable.

Parking lots pocked with potholes.

Signs, even warning signs, too faded to be read. (And only in English.)

Beaches without lifeguards or emergency telephones.

Harbors that are too crowded with long lists of commercial tour boats waiting for dock space.

As with most of state government the past decade, the DLNR is strapped for cash and has been forced to cut back in all its divisions.

The lack of maintenance is obvious in state parks on Kauai. Far more than on any other island, the tourism industry on Kauai depends on the state to care for most of the attractions visitors come to experience.

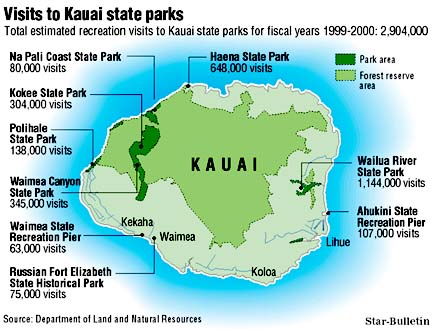

Hawaii has 26,000 acres of park land statewide and more than half that total is on Kauai. Yet in the past five years, state parks on the island have received no more than 18 percent of the state parks operating budget for the entire state. Between 1991 and 2000, Kauai received 13 percent of the capital improvement money allotted for parks.During 1999-2000, according to the DLNR, the state parks on Kauai were visited an estimated 2.9 million times, and 95 percent of the park users were tourists. (Kauai hosts about 1 million tourists annually, and most visit several state parks.)

Also, the state parks on Kauai are dangerous. Four of the 10 drownings so far this year on Kauai have been at state parks.

Since 1970, 28 people have drowned at Hanakapiai, the deadliest beach on Kauai, which is part of the Na Pali Coast State Park. A dozen people have drowned at Polihale State Park during the same time period.

There are no lifeguards on any state park beaches on Kauai. Some, like Hanakapiai and Polihale, have no emergency telephones to call for help.Each year, the Kauai Fire Department overspends its helicopter budget airlifting visitors with broken ankles, sprained knees and cracked ribs off badly eroded state trails. Navy helicopters from the Pacific Missile Range on Kauai frequently assist in searches for hikers lost on state trails.

In May 1998, then newly-appointed DLNR Director Tim Johns made his first speech to Kauai's largest coalition of tourism industry leaders, members of the Poipu Beach Resort Association.

Johns acknowledged state facilities on the Garden Island are in bad shape, but he pleaded poverty. The DLNR always has and always will receive only 3 percent of the state budget, he said.

"I can't print my own money," Johns said.

When Mayor Maryanne Kusaka asked the status of new public bathrooms at Kee Beach, Johns told her they were in the "design phase." Kusaka, who prides herself on being the portrait of aloha, was livid."Twelve years ago we (the county and state) started a plan for Kee Beach. Twelve years later there isn't a plan," she told Johns. "We have portable toilets. We have summer coming up and it's going to be a zoo again."

Johns left without making any promises to seek increased funding or look for new funding sources.

Agency a bureaucratic maze

Little has changed in the past year and a half."The communication is a little better, but only when we initiate it," said Sue Kanoho, who heads the Kauai Visitors Bureau.

Kanoho pointed out one of the major frustrations is simply a matter of how the agency is organized:

For example, if you rent a kayak and it's on the bank of the Wailua River, you're on land that belongs to the Parks Division.

But while you're paddling the Wailua River itself, you're on water that's in the jurisdiction of the Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation.

Neither division has its own enforcement officers. They come from a third agency, the DLNR's Division of Conservation and Resource Enforcement, which will cite people for violations whether they're on the river or on dry land.

But with only 14 officers for the entire island, enforcement is spotty at best.If the divisions disagree on an issue, the dispute can be resolved only at Johns' level, where access is extremely limited. "You'd have a better chance of getting an audience with the pope," grumbled one frustrated DLNR manager.

Johns responded to five requests for an interview for this article with written answers to some questions.

He said the economic downturn of the 1990s hit the DLNR hard, some divisions harder than others.

DLNR's Forestry and Aquatic Resources were able to attract federal funds and, while their budgets didn't grow, they "were pretty much able to tread water."

The State Parks division relies more on the state general fund. Its budget statewide was cut by one-third -- to $6.3 million in 2000 from $9.4 million in 1995, Johns said.

Last year, State Parks won legislative approval to use fees it collects for any purpose in the division, including maintenance, Johns said. Previously the fee income was earmarked for interpretive programs.

The State Parks division will be asking for increased operating funds and the ability to issue bonds for construction in the next session, he added.

An effort by the Forestry Division to increase hunting license fees was defeated by the hunting lobby, he noted.

Johns said that with the upturn in the economy more state funds will come to the DLNR budget and the agency will continue to seek out alternative funding methods.

Sierra Club files lawsuit

Since they rarely agree on anything, it would seem that if the tourism industry is disappointed with DLNR, the environmentalists would like the agency.Not exactly.

"The horrible condition of DLNR facilities on Kauai are the example I always use to explain why we filed our lawsuit," said Jeff Mikulina, state director of the Sierra Club.

The group recently filed a court challenge contending the state violated environmental laws when it created the Hawaii Tourism Authority in 1998 to promote tourism without an environmental impact study to determine what additional tourists would do to the state's natural resources.

"The state is spending $60 million a year on advertising and nothing on the natural resources they're asking the tourists to come and see," Mikulina said. "That's what our lawsuit is all about -- the state doesn't have the resources to deal with the visitors it has now, let alone additional visitors, in a safe manner for both the tourists and the natural resource."

How bad is it? A veteran backpacker coming down from the Kalalau Trail recently remarked to activist Ray Chuan, chairman of The Limu Coalition, a Kauai environmental organization: "Most places I hike I'm constantly watching the beautiful scenery. Here, I'm constantly watching my feet to keep from falling and breaking my neck."

Chuan and a small group of volunteers recently completed a yearlong study, counting and interviewing hikers at the head of the Kalalau trail.

The Kalalau trail begins at the very end of Kuhio Highway. There is no parking lot. Tourist rental cars line the highway, often parking in mudholes. They park on side roads. They park in an open field that is supposed to be a landing pad for rescue helicopters.

Chuan's survey found an average of 350 people a day hike the Kalalau Trail. About 80 percent go only the first two miles to Hanakapiai Stream and return. But that is the toughest part of the trail: very steep, badly eroded and usually very wet and slippery with large boulders to climb over and exposed tree roots crisscrossing the trail in many places.

Most of Kauai's other popular hiking trails are in Kokee and Waimea Canyon, both state parks and both on the checklist of every visitor. Samuel Clemens -- Mark Twain -- first described Waimea Canyon as "the Grand Canyon of the Pacific," and the tropical forest around nearby Kokee draw hundreds of thousands of visitors annually.

At the end of Kokee Road are two lookouts about a mile apart that offer spectacular and endlessly photographed views of the Kalalau Valley. Last year, the road between them was closed for six months because the potholes became so bad that vehicles could no longer get through, and there was no money to patch the asphalt.

Adjacent to the parks are vast areas of State Forest Reserve that include more than a dozen of the island's best hiking trails, many good four-wheel-drive roads and most of Kauai's best pig hunting.

Access to hiking trails difficult

The hiking trails are administered by Na Ala Hele, a branch of the DLNR's Forestry Division that has been experimenting with licensing professional trail guides.But the parking lots at the trail heads belong to the DLNR's Parks Division, which won't allow commercial guides to park there to hike the Forestry Division's trails. As a result, only one of the many trails in the Kokee-Waimea Canyon area is available for commercial guides.

Then there's Polihale State Park, one of the most beautiful beaches in Hawaii, with breathtaking sunsets and beautiful views of both Niihau and the Na Pali Coast. Problem is, a tourist can't get there from here.

Polihale is connected to the Kaumualii Highway by five miles of sporadically maintained, red dirt, cane-hauling road. Most rental car contracts prohibit taking vehicles off paved roads in general and some specifically mention Polihale.

Johns puts a $15-million price tag on fixing all the DLNR facilities that are broken on Kauai. But the fact is: nobody really knows the cost.

State Sen. Jonathan Chun, whose district covers about two-thirds of Kauai, said there is support in the Legislature for additional funding to improve DLNR facilities, but no one in the Legislature knows how much the agency wants or needs. An unintended consequence of the governor's efforts at holding the line on department budgets has resulted in state agencies being far less than truthful at budget time, Chun said.

"DLNR can come in and ask for $1 million for a certain park when what they really need is $10 million," Chun said. "But if they tell us $10 million, they're going to be in a lot of trouble with their boss. So we all just stumble around in the dark instead of acting on valid information."

It goes even deeper than that, said Lynn McCrory who has just begun her second term as Kauai's representative on the Board of Land and Natural Resources, which sets policy for the department. McCrory said the department needs to look at its resources and the public needs and decide what to develop and what to leave alone. Most basically, it needs a plan. And before it makes a plan, DLNR needs a vision of how things should be, she said.

"Some people like a guided tour with paved walkways and informational signs and park rangers to answer their questions. Other people really want a wilderness experience with no facilities at all. National parks like Hawaii Volcanoes on the Big Island do a wonderful job of addressing all levels of interest and activity."

"We need to define the experience we want to offer and then we need to fund it," she said.

LIHUE -- Ask Kauai's tourism industry and environmental leaders what the island's state parks should be like and they all point to the same place: the Kilauea Lighthouse. Kilauea Wildlife

Refuge has signs,

parking, visitor centerThe manager of the 31-acre park

says his priority is a safe area

for visitors and clean toiletsBy Anthony Sommer

Kauai correspondentThe Kilauea National Wildlife Refuge, run by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, has indoor and outdoor displays, informational signs to help visitors identify different bird species, a visitor center and two paved parking lots.

Dave Aplin, the program manager for the refuge said he operates under this philosophy: "We need to provide a safe area for visitors and we need clean toilets. After that come all our other programs."

The 31-acre refuge is centered on the lighthouse, built in 1913 and decommissioned in 1976. The original light has been replaced by a flashing strobe, but is turned on for special events such as New Year's Eve.

The refuge is home to thousands of seabirds, including a large population of albatross that return here to mate. Located on Kilauea Point with the ocean on three sides, it's also one of the best whale-watching sites on the island. The facility hosts several festivals and special events throughout the year.

The refuge has a full-time paid staff of five. But what's most impressive is a corps of 80 local volunteers, who do everything from restoring habitat to serving as docents and trail guides.

Two bird-watching hikes up Crater Hill are provided for visitors every day by volunteers.

The entry fee is $2 per visitor, but the refuge makes extra money through the Kilauea Point Natural History Association, a non-profit volunteer group that runs the bookstore and gift shop.

The proceeds are used for refuge programs.

LIHUE -- Run-down, beat-up state facilities for both tourists and residents are a state problem that is most visible on Kauai. Fund-raising

ideas surface

in ’98 reportTaxes and higher fees could

fund needed park repairsBy Anthony Sommer

Kauai correspondentObservers say what it comes down to is a lack of money. And lack of a master plan.

"There is no plan for the future," said one DLNR program manager. "We're too busy always playing catch-up without enough funding."

Almost all the DLNR's revenue comes from the state's general fund.

But laws already are in place allowing the agency to keep money it collects for various fees and permits.

Last month, the agency's Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation unveiled a plan to double many of its fees in stages over the next few years.

Other DLNR division have not announced similar increases, however.

In a May 1998 report to Gov. Ben Cayetano, a blue-ribbon panel of private industry leaders he appointed the year before issued a report, "Investing in Hawaii's Natural Resources."

"It was agreed that immediate steps are needed to assure that long-term funding mechanisms are in place so that Hawaii's environment will be protected in the future," said the committee.

The group found the quality of Hawaii's environment and the state's economic vitality, particularly tourism, are directly linked.

"Demand for Hawaii's ground water is increasing, major fisheries are crashing and alien species are invading our mountain watersheds and near shore areas. Our state parks are in disrepair and our precious native species are going extinct," the study found.

Gary Baldwin, Kauai's representative on the Hawaii Tourism Authority, said he stumbled over the study quite by accident.

Now, he and Lynn McCrory, the island's voice on the Board of Land and Natural Resources, are looking closely at its recommendations.

A report from a joint HTA-DLNR survey of all state recreational facilities is due in December.

Once the needs are determined, the price tags will emerge.

The committee report looks at a number of possible ways of raising more money for state facilities:

The committee also noted there are numerous federal funding sources available, but most require matching funds.An income tax check-off box: This would set aside a set amount of taxes, usually $1, for natural-resource protection. Thirty five states use it and raise a total of $11 million annually.

A state lottery: Arizona earmarked a share of state lottery revenues for its Game and Fish Heritage Fund. It yielded $5.9 million the first year and two years later, $10 million was raised.

Sales tax: Missouri allocates 1/8 of 1 percent of its state sales tax to conservation programs. In its first year the tax produced $55 million.

User fees: Most of the money raised by states for conservation comes from hunting and fishing licenses. The report noted that Hawaii has the cheapest hunting licenses in the nation, no ocean fishing licenses and little or no recreational user fees.

Taxes on recreational equipment: Many states now tax equipment, such as backpacks, hiking boots and kayaks, for a wide variety of outdoor recreation activities and use the proceeds for conservation programs.

It recommended a small, but consistent, portion of the state's general fund be set aside to match federal grants.

While there is agreement state facilities need money, there is less agreement on who should pay it.

Some say the user fee would be the fairest because the people who use the resource would pay for its upkeep.

Others argue the entire economy benefits from the use of natural resources by tourists, so everyone should pay a portion.

From time to time, environmental groups have proposed turning over the Na Pali Coast State Park -- and possibly even the adjoining Kokee and Waimea Canyon state parks -- to the federal government to operate under the National Park Service.

The hope is the area would be upgraded to the same standards as Haleakala National Park on Maui and Hawaii Volcanoes National Park on the Big Island.

Every time the idea surfaces it is beaten down by opposition from Kauai's hunters who fear national-park status would limit hunting and cut off many access roads they now use in state forest land.

The region includes many of the best hunting areas on the island.

"The political facts of life are that there are many more pig hunters on Kauai than environmentalists and they have a powerful lobby," Baldwin noted.