Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Like other Hawaii business owners, gas station dealers on Oahu struggled through much of the 1990s. Many wondered when the state's lackluster economy would rebound and help bring back better times.

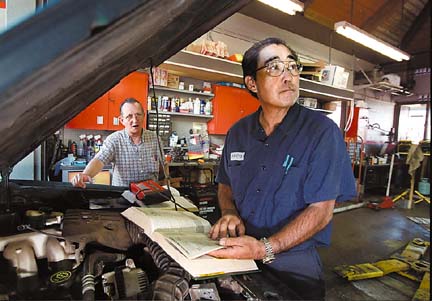

Oahu dealers say business

has never been worseBy Rob Perez

Star-BulletinNow that the economy is rebounding, dealers are still wondering. For some, business has never been worse.

It has been so bad that over the past two years, a handful of station operators have turned in the keys to their leased facilities and walked away without so much as a dime. Less than a decade ago, that would have been unheard of. The dealers could have sold their interests for tens of thousands of dollars, some for more than $100,000.

But because the stations were losing money or barely turning a profit, no one was interested in paying to take over, the dealers say. Some dealers did not even bother to test the market.

Nolan Matsushige two years ago walked away from a King Street Texaco station for which he and his brother paid $150,000 to take over in 1989. When they gave up the business, they got nothing back.

A monthly rent of nearly $16,000 proved too burdensome, especially considering revenue from gas sales did not come close to covering the station's overhead, Matsushige said. Never mind that Matsushige was working six to seven days a week, up to 14 hours each day -- not an uncommon schedule for some dealers.

"We couldn't hang on anymore," the former Texaco operator said. "It was too hard, too stressful."What Matsushige went through underscores the difficulty many Oahu dealers face today in trying to survive in a supercompetitive, changing market.

The competition has become so keen that dealers say they sell gas barely above cost to keep price-sensitive customers from buying elsewhere. Some dealers say they actually sell at a loss once credit-card fees and excise taxes are factored in.

"We basically had to give the gas away," said Lindsey Asari, a Shell dealer until recently.

On top of that, dealers are having to contend with rising costs, including rents that at some stations have jumped dramatically in recent years.

If a dealer does not have a thriving food mart or car repair operation to offset puny gas margins, the station can become a financial drain, like an engine with a persistent oil leak.

Leroy Yamamoto said the Arco station he ran on Dillingham Boulevard for nearly 20 years was losing a minimum of $4,000 a month when he decided to give back the keys last October. He estimates he could have sold the business for at least $150,000 in better times. But last October, he got zilch.

Nothing to show for effort

Yamamoto, however, was able to sell another station in Kaneohe only several months ago, which he attributed to good timing and luck. He still runs an Arco in Hawaii Kai, but he said the economics of that station, like the others, are not good."We're really, really getting squeezed every which way you can think of," Yamamoto said.

Les Funai, who has run a Chevron station in Kaneohe for the past 12 years, wonders whether he can last beyond the end of the year. He figures it is pointless to try to sell the station. He said he's working at least 12 hours a day, sometimes seven days a week, yet has nothing to show for the effort.

"We're not making any money. We're getting deeper and deeper into the hole," Funai said.

If dealers walk away from their stations, the gas companies can operate the sites for up to two years. If the stations are open beyond that, they must be leased back to dealers, according to a state law that the companies criticize for restricting the free market. Some companies have supported efforts, so far unsuccessful, to repeal the law.

The law's proponents say it preserves competition by preventing oil companies from driving out dealers and gaining control of too much of the marketplace.

Dealers, however, are leaving the market anyway -- and some put the blame squarely on the oil companies.

Dealers accuse oil firms

New leases are structured much more favorably to the companies, rents are increasing dramatically, dealers are being forced to shoulder more costs -- these are among the factors critics cite to argue that the companies have long been trying to get rid of dealers across the country.What's more, some dealers say, the companies in recent years have slowly squeezed margins by raising wholesale gas prices to Oahu dealers and not increasing pump prices by like amounts at the company-operated stations, which compete with the dealer stations.

When that happens, dealers say, they cannot pass the full price increases to customers, further shrinking profit margins.

In the 1980s, margins averaged more than 20 cents a gallon, dealers say. Today the margins can be as little as 3 to 6 cents on Oahu. On the neighbor islands, dealers enjoy much higher spreads."The oil companies want to take over, and they're doing what they can to eliminate dealers," said Dick Botti, executive director of the Hawaii Automotive Repair and Gasoline Dealers Association.

Federal law prohibits oil companies from arbitrarily terminating a dealer's lease. But there are other ways to get rid of dealers, critics say.

"You eventually evict them by making them broke," Botti said.

Chevron Corp., the market leader in Hawaii, dismisses such allegations.

Marketplace changing

Chevron says it is working more closely than ever with its dealers, recognizing that they have to do well for Chevron to do well. Chevron has 48 stations on Oahu, but only five are run by the company; the rest are dealer stations, owned (with one exception) and supplied by Chevron but operated by independent business men and women."In the end, the success of Chevron is tied very closely to the success of our dealers," said Ken G. Smith, Chevron's marketing manager in Hawaii. "We've got to collectively figure out how to beat up on the competition and not on each other."

Officials from other gas companies could not be reached for comment or did not return phone calls.

Smith acknowledged that dealers face difficult challenges in today's market, but they also are shielded by Chevron from major liability and regulatory costs.

What is happening in the gasoline business, Smith added, is essentially no different than what is happening in other industries, where mom-and-pop operations are under intense pressure because of changes in the marketplace.

The ones who can adapt to the changes and deliver what customers want are the ones who will succeed, and that's true also in the gas business, Smith and others say.

Despite the difficulties facing Oahu dealers, not all are struggling. Dealers in prime locations with good facilities are able to sell large volumes of gas, generating enough income to cover overhead, dealers say.

'I can't give it away'

But many of the smaller stations in not-so-prime locations are ill-equipped to compete and face dismal futures, they say."I don't think you'll see (small dealers) in the next five to 10 years. They'll be forced out of existence," said Asari, the former Shell dealer who left the business in August after 17 years.

Hawaii already has seen dozens of stations close in recent years. Based on the most recent data available, the state had 369 gas stations in 1996, down 21 percent from a decade earlier, according to the dealer trade association.

Many stations closed after landowners decided to sell the properties or use them for other purposes. Higher costs related to increased regulatory requirements also contributed to the trend.

Some say fewer stations means less competition, which leads to higher prices and fewer consumer choices on where to buy gas or get a tire fixed.

While the number of stations statewide has been shrinking since the 1970s, the practice of walking away from a station empty-handed has only surfaced in the past several years, dealers say.

In some cases, dealers have given up stations that were in their families for several decades. If they try to sell, they typically have few or no assets to offer -- only an opportunity for someone else to operate the station and generate income.

Years ago, that opportunity was worth a lot.

Chevron dealer Frank Young remembers his family getting a $750,000 offer in 1989 for the station they run in Kakaako. His father was not interested in selling then.

"Today I can't give it away," Young said.

In the case of Matsushige, the former Texaco lessee, he is reminded monthly of how much the tables have turned for dealers, even though he no longer is one.

Matsushige still is making monthly payments on the loan he and his brother got when they took over the Texaco station 11 years ago.