Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

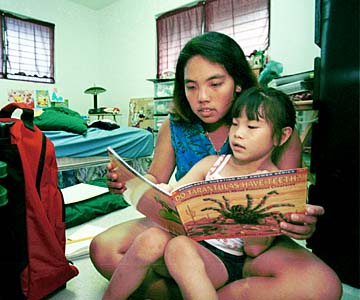

It’s payback time AS a new teacher at Kaala Elementary School, Heidie Abrazado earns about $1,200 a month. After taxes and benefit deductions, her income shrinks to about $650.

for outstanding

student loans

Fewer isle students now default,

but they still lag behind

the rest of the U.S.By Suzanne Tswei

Star-BulletinBut every month Abrazado faithfully sets aside $400 to repay her college student loan.

"It's not easy -- especially when I have an 8-year-old daughter -- but I know I have to do it. It's my responsibility. That loan made it possible for me to get my degree," the 26-year-old Abrazado said.

Earning a bachelor's degree in early childhood elementary education had been a lifelong goal, and she is proud to be the first person in her family to earn a college degree.

A $20,000 student loan over three years made it possible for her to attend Chaminade University of Honolulu full time while she cared for her young daughter.

Abrazado graduated in December and began paying back the loan as required after she was hired at the Wahiawa school.

To make ends meet, she lives with her fiance and shares expenses.

"I have not missed a single payment. Of course, it would be better if I could wait (to repay the loan) until I could make more money. But I am very grateful for that loan. I don't complain at all when I write out that check for $400," Abrazado said.

Thanks to college graduates such as Abrazado, Hawaii is following a national trend: fewer borrowers are defaulting on their student loans, according to a study released this week by the U.S. Department of Education. However, while Hawaii's default rate has improved, the latest numbers still reflect the islands' pattern of being worse than the national norm.The study shows Hawaii's student loan default rate was 8.2 percent between October 1998 and September 1999. That compares to 10.3 percent from the previous federal fiscal year. The 1998-9 national average was 6.9 percent, a decrease from 8.8 percent the year before.

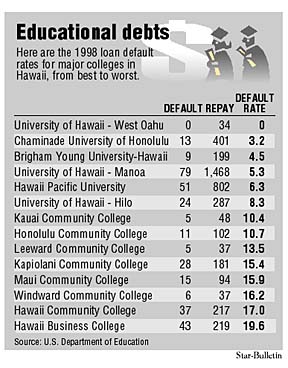

The best rates in Hawaii tend to be among the private institutions, while the worst rates belong to the University of Hawaii's community colleges (see box). Hawaii's economic difficulties in recent years may have made it difficult for borrowers to repay their loans, local officials said. The numbers should improve as the economy regains its footing, they said.

One reason for the improved rates, nationally and in Hawaii, is a change in the law that altered the definition of default from 180 to 270 days without payment. Hawaii officials also attribute Hawaii's decline in defaults to responsible borrowers and stepped-up counseling.

"WE are lucky. We've got good students," said Eric Nemoto, financial aid director for Chaminade University, which had a 1998 default rate of 3.2 percent. The national average for private institutions was 4.7 percent, which traditionally has been lower than the national overall average.

"It may be the nature of the school. Maybe the fact we are a Catholic school has something to do with it. But I think the main reason is we make sure we do our share of counseling and intervention to make sure students understand what their responsibilities are."

Brigham Young University-Hawaii, whose student body is about 95 percent Mormon, also scored above the national average, with a default rate of 4.5 percent.

"I don't want to say our students are better than anyone else, but they are good, responsible students. They are taught to be honest, and they have to sign this honor code when they are admitted to the school," said Steven Bang, BYUH's financial aid director.

The school makes an effort to provide necessary personnel to counsel students on their financial-aid options and responsibilities, he said.

Loans, meant to help pay for tuition and school-related expenses, are guaranteed by the federal government and provided by banks and other private institutions.

Both Bang and Nemoto said student loans are important to the success of their schools, helping to boost enrollment. The loans help students in the middle- and higher-income brackets who do not qualify for need-based financial aid.

"The student loan's impact to enrollment has been significant," Nemoto said, noting undergraduate enrollment has increased to 994 this fall from 659 in 1995. The increase in enrollment has mirrored the increase in loans, he said.

CHAMINADE students are receiving about $10 million in loans this year compared to $3.3 million in 1995.

Bang said borrowers at risk of defaulting on their loans tend to be students who drop out in their first year of college. Schools that have discretion over student admissions tend to have fewer problems with loan defaults, he said.

The worst rate in Hawaii belongs to Hawaii Business College, with 19.6 percent. Leighton Kato, the school's financial aid director, said having no advisor to track students and provide counseling caused the high default rate. But the school stepped up counseling efforts and expects to see a big improvement for 1999.

The University of Hawaii's community colleges, which have an open-door admissions policy, scored mostly below the national average of 10.7 percent for comparable schools. But two campuses recorded rates better than the national average: Manoa at 5.3 percent and West Oahu with a zero default rate.

JoAnn Yoshida, financial aid specialist for the UH system, said she had no explanation for the differences.

"We've never done a study on why, so I don't know. My feeling is that the economic situation in the islands is not as good as that on the mainland, and that may have something to do with the default rate," Yoshida said.

The fact that community college students tend to be more transient, or single parents with lower incomes may contribute to the double digit default rates, she said.