Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

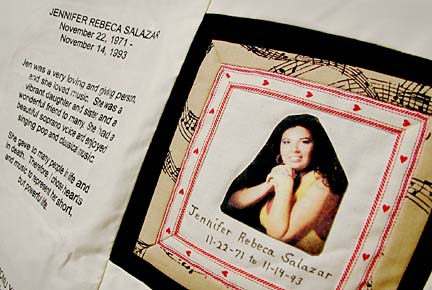

A picture of Jennifer Rebeca Salazar smiles from a red-and-black patch, adorned with musical notes, on a unique Hawaii quilt.

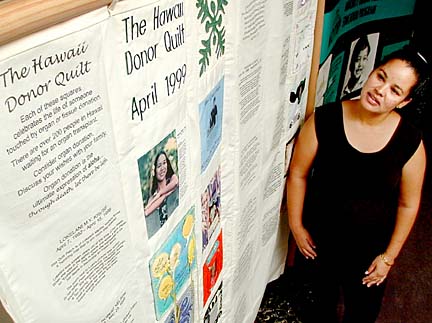

The Hawaii Donor Quilt

remembers those whose lives

were touched by organ donationBy Helen Altonn

Star-BulletinStruck by a car while running across a street, Jennifer died on Nov. 13, 1993, eight days before her 22nd birthday.

Her story and others of loved ones lost are told with poignant messages on a Hawaii Donor Quilt, now about 5 feet by 6 feet in size, commemorating organ and tissue donations.

Seven-inch-square patches remembering each person are made using thread, crayons, paint and markers.

Some include parts of sentimental items, such as baby blankets and high-school jackets, photographs, poems or symbols.

Jennifer was attending Butte College in Chico, Calif., when she died. Her mother, Ardeth Weed of Kailua-Kona, who lived in California at the time, said the decision to donate her daughter's organs "was a no-brainer."

The issue was debated in Jennifer's high-school English class."She came home and said she was going to be an organ donor when she got her (driver's) license," Weed said.

Weed offered to do a square in Jennifer's memory for the National Kidney Foundation's National Donor Family Quilt, but said it took her six years to make one. "I guess I just needed more time." It's now part of the Hawaii quilt.

Jennifer's patch says: "Jen was a very loving and giving person, and she loved music. She was a vibrant daughter and sister, and a wonderful friend to many. She had a beautiful soprano voice and enjoyed singing pop and classical music.

"She gave to many people in life and death."

Jennifer's heart went to a middle-aged man; one kidney went to an older man who had been on dialysis two years, and the other went to a 12-year-old girl, now 19.

"I just am really happy that somebody else can live a longer life and have a better quality life because of Jenny's gift," Weed said.

The perpetual Hawaii quilt is more inclusive than the national quilt -- representing all whose lives are touched by organ donation, said Donna Pacheco, heart and liver transplant coordinator at St. Francis Medical Center.

Patches may be contributed by organ donor families, families of transplant candidates who don't receive a donation and those who want to be donors but can't for various reasons.

"It has such visual impact and meaning," said Felicia Wells-Williams, aftercare coordinator for the Organ Donor Center of Hawaii. "It's really meaningful for families to read other stories, and their own."

Two donor mothers initiated the quilt with help from the center and community volunteers.

Families who lost loved ones and consented to organ donation were invited to take a square to the annual Donor Family Memorial Service in April 1999.

All those present helped to stitch a central patch with the 'ulu, or breadfruit, signifying the gift of life.

Jeanne Callahan of Kauai is finishing the patch. She also has one on the quilt in memory of her husband, David W.J. Callahan. It is a copy of a block he designed for a quilt she made named, "Ku'u Aloha no Ku'umau Keikikane," meaning "the love of our four sons."

"He was a warm, friendly and likable man. Very artistic," the message says. "This block was selected because it's symbolic of the family man he was. Not physically here with us, but never out of heart or thought."

Callahan's husband died Aug. 19, 1997, at age 66. He was giving their dogs a last walk before they left on a trip to Oregon.

"He never came home," she said. "He had cardiac arrhythmia."

They had discussed organ donation many times and there was no question about it. "It was like a part of him that was living on and someone was benefiting from it. If roles were reversed, and he was the recipient, I would appreciate it. My boys are all organ donors also."

Callahan said she has a friend on Kauai waiting for a liver and another one from Kauai in California waiting for a heart.

Twenty-seven donor families have participated in the quilt thus far, creating what will probably be just the first panel, Wells-Williams said. The national quilt has 17 panels.

Those who see the Hawaii quilt are dramatically affected by the stories, said Robyn Kaufman, Organ Donor Center of Hawaii executive director.

For example, a turtle symbolizes the presence of 12-year-old Joshua for a Waianae family who spent a lot of time together on the beach. A cousin wrote on the patch:

"Lo and behold, a turtle appears from nowhere, bobbing up and down, moving with the ocean's waves where his ashes are scattered.

"With feelings of sadness and joy at the same time, we watch the turtle as each of us silently say a prayer and talk to Joshua as we start placing our flowers and leis on the stonewall and rocky shore, also throwing some into the ocean while watching this one turtle still in view frolicking around.

"We leave the area with feelings of complete tranquility and happiness knowing Josh was with us for awhile. Thank you Josh. We love and miss you so much."

Families have an opportunity to pin patches on the quilt twice a year.

The next pinning will be held as part of a Donor Sabbath Observance Nov. 11 at the Royal Garden Hotel in Waikiki.