Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

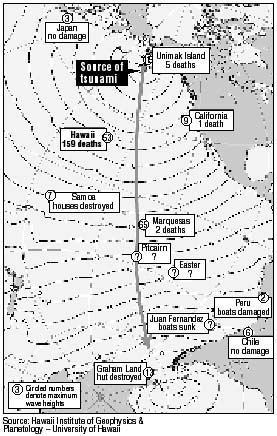

Preparing for MORE than half a century later, scientists are beginning to piece together the puzzle of an April 1, 1946 tsunami that killed 159 people in Hawaii, smashed into the Marquesas Islands and kept going to Antarctica.

next big tsunami

Scientists travel across the Pacific

to study the 1946 tsunami that killed

159 in Hawaii; their work may help

create a warning system that will

save lives the next timeBy Helen Altonn

Star-Bulletin"The '46 tsunami is a huge, huge enigma," said Gerard Fryer, associate professor in the University of Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology.

It's a big worry because it hasn't been explained, he said. "The waves were way, way too big for the size of the earthquake (that generated it). We're trying to figure out everything we can about that."

Waves more than 100 feet high destroyed a lighthouse and killed five people on Unimak Island, Alaska, after a magnitude 7 earthquake in the Aleutian Islands.

Besides the Hawaii and Alaska victims, there was one death in California and two in French Polynesia -- a total of 167.

Fryer said the earthquake alone doesn't explain the large waves, but it shook loose a huge submarine landslide into the Aleutian Trench.

The combination possibly caused a narrow beam of very large waves, he said. "They just missed Hawaii but clobbered the Marquesas."It's unlikely another tsunami as powerful could surprise Pacific nations and islands because it resulted in an international warning system, said Fryer, a state civil defense tsunami advisor.

However, the size of the waves could be seriously underestimated, he said. "We have to work out exactly what happened in 1946 so that the next time something happens, emergency managers around the Pacific can give the appropriate warnings."

THE last damaging tsunami across the Pacific was in 1964, Fryer said.

"The one thing we know for certain is that there will be a next time," said Emile Okal, Northwestern University professor of geological sciences.

Okal and Costas Synolakis, University of Southern California professor of civil and environmental engineering, joined Fryer in a recent survey of the 1946 tsunami's effects in the Marquesas.

Also participating were Daniel Rousseau of USC and Gerard Guille and Philippe Heinrich of the French Atomic Energy Commission. The commission and National Science Foundation funded the work, resulting in "a wealth of information," Fryer said.

Hawaii and the Marquesas, the northernmost group in French Polynesia, are particularly vulnerable to tsunamis because they have almost no offshore reefs, he pointed out.

The large waves that raced across the Pacific in 1946 ran up the western coast of Antarctica to a height of 12 feet, he said. A British Antarctic Survey hut was destroyed.

The scientists were amazed at what they learned about the tsunami in the Marquesas.

Noting the people there only recently got television, Fryer said, "Before, they would tell stories to the kids, who passed on the information. Kids would tell us, 'Grandpa said there was a boat in this tree.' "

The waves were larger there than the highest 56-foot waves in Hawaii, he said. They averaged 20 feet "and reached up phenomenally high -- as much as 65 feet --in narrow valleys."

But the mid-day tsunami made a lot of noise; the first wave wasn't the largest, and people heeded warnings and escaped, the scientists learned.

"There was a rapid flooding of the land but nobody was overtaken by a wall of water," Synolakis said.

The scientists went from one village to another by four-wheel-drive truck, boat and helicopter to interview eyewitnesses who were mostly children in 1946.

They saw evidence of tsunami damage that occurred 54 years ago, such as a wrecked church or a coral boulder left by the waves.

They measured the maximum height reached on shore with standard gear and used the global positioning system to calculate the distance from shore.

They hoped to get two or three measurements from each of three islands, but obtained more than 40 from 25 villages on five islands.

Fryer said the scientists went to the southern island of Fatu Hiva last year to investigate a little tsunami that happened after a cliff collapsed.

They asked about other tsunamis and were so intrigued by what the people remembered about 1946 that they decided to go back this year, he said.

ACCORDING to the people's accounts, the ocean retreated in the early afternoon of April 1, 1946, exposing rocks usually covered even at low tide. The ocean returned, hissing, and flooded the shore.

It subsided as much as 100 yards in some bays, then roared back faster and higher. The third wave was immense, then it slowly died.

The people had fled to high ground but the receding water captured trees, homes and livestock. Branches, coconuts, broken boats and houses, and thousands of stranded fish littered the coasts the next day.

A woman and her baby drowned in a village washed away by flooding more than half a mile inland on the island of Hiva Oa.

Fryer said the Marquesas findings have raised more questions.

For example, he said, there had to be big waves at Pitcairn and Easter Islands. But, how high?

There are also rumors that the San Juan Fernandez Islands between Easter Island and Chile had very large waves, he said.

"We realize we've got to get moving and get information before all the people who know it die."