Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

hampagne and flowers are lost on Lady Shrimp. To get her in the mood for the wild thing, it helps if you first remove one of her eyes.

Learning to breed and feed

ocean creatures is the

mission of the 40-year-old

Oceanic InstituteMoi bettah pan-fried

By Betty Shimabukuro

Star-BulletinShrimp produce hormones in their eyes, including a hormone that inhibits spawning. Remove an eyestalk and, well, it's cha-cha time.

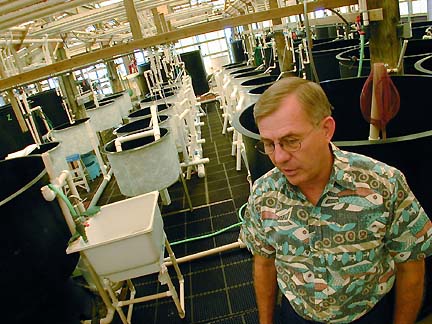

At the Oceanic Institute, researchers specialize in the romantic inclinations of fish and shrimp. They'd undoubtedly put their work in far more scientific, less prurient, terms, but it boils down to this: Get the mommy fish and the daddy fish to have baby fish; keep the baby fish fed and happy until they become mommy and daddy fish themselves, or until they become dinner.

This is called "closing the life cycle," and it involves figuring out what to feed each species through each of its life phases -- while working out every other detail of its living conditions as well.

A 40th-anniversary party for the Oceanic Institute features seafood raised by the institute and prepared by chefs including Philippe Padovani, Jean Marie Josselin, Alan Wong and Hiroshi Fukui: CELEBRATION

UNDER THE STARS

Dinner time: 6 p.m. Aug. 30

Place: Royal Hawaiian Hotel Coconut Grove lawn

Tickets: $100

Call: 537-8610

Once the cycle has been perpetuated for a couple generations, techniques are taught to aquaculture farmers.

A cash crop is born.

The Oceanic Institute is turning 40 and celebrating with a party honoring its success stories. The honorees get to be dinner -- here we're talking the Pacific white shrimp, many pounds of moi and an experimental newcomer, a fish called kahala.

A prestigious line-up of chefs will show what can be done with these grown-in-Hawaii products, freshly harvested from the institute's 50-acre Makapuu research site.

The idea, says Thomas Farewell, president and CEO, is to spread the word among the community's movers and shakers about what the institute has accomplished and stands to accomplish in the future.

Here's the quick take: The Oceanic Institute was founded in 1960 along with Sea Life Park by a visionary named Taylor "Tap" Pryor, who sought to create a cooperative entertainment/research facility that would also explore the undersea world through submersibles launched from his Makapuu Pier. The collective's early work was in dolphin and porpoise research.Eventually, the nonprofit institute separated from the for-profit Sea Life Park, which remains its tenant on 50 acres of neighboring land. The institute's focus shifted to aquaculture and biotechnology.

Its first key scientific breakthrough was to close the life cycle of the mullet, and later the milkfish. This probably doesn't sound too sexy, because these are not sexy fish, but the techniques learned did wonders for markets in Asia. Next came mahimahi, which proved too expensive to cultivate, but the knowledge acquired led to the institute's more recent and flamboyant success with moi.

Moi -- also known as Pacific threadfin -- is a fish of such value that in ancient Hawaii it was reserved for royalty. This fish has sex appeal. It could well become an export fish for Hawaii.Farewell recalls that researchers surveyed fishermen, asking if they thought they could sell moi. The answer was no. "They said, 'If I caught a moi, I'd take it home to my mother. I wouldn't sell it to anybody.' "

Next graduate of the Oceanic Institute will probably be kahala, or amberjack, a larger, faster-growing fish than moi. Last October 1,000 kahala were test-marketed at a Daiei store. They were all gone in a couple of days. Kahala's potential exceeds moi, Farewell says, largely because it grows big enough to easily filet, a plus in mainland markets.

Now here's a little-known fact from the fish world: Moi is limited in size because at 5 to 7 months of age, the boy moi (and they are all boys at this point) start turning into girl moi. They put all their energy into this sex change and stop growing. To keep nurturing them through this period is costly, so most moi go to market at this size, 1 to 2 pounds.Kahala doesn't undergo this gender transference.

Chef Hiroshi Fukui of L'Uraku, who is preparing kahala for the anniversary celebration, says the fish is unlike anything else in Hawaii. It has a well-balanced oiliness that makes it ideal for sashimi -- the ultimate test of a fine fish, he says. "You can marinate it, grill it, saute it -- it's versatile, really nice. It has great potential."

That said, you can't have any, unless you put down $100 for a ticket to the party. Kahala in the open ocean is prone to ciguaterra and parasites. The institute's fish have spawned just once in captivity and researchers estimate they are two years away from passing their technology on to farmers.

A commercial reality now, however, is moi. Research began in the 1980s, building on theoretical work that had been done at the University of Hawaii a decade before. The result has been hundreds of thousands of moi fingerlings distributed free to farmers in the islands, along with the expertise in raising them to market size. Also: an experimental project off Ewa Beach in cooperation with the UH Sea Grant College has successfully raised moi in underwater cages.

A few years ago, moi started showing up on restaurant menus as chefs caught on to its delicate taste and texture. In the last few months it has become available to common folk, although at prices up to $9 a pound. It is now, along with tilapia and Chinese catfish, among the three top fish of the island aquaculture industry.

And this is only the beginning. "The sex appeal of moi really could reach beyond Hawaii," says John Corbin, manager of the state's Aquaculture Development Program. "If we could deliver poundage we could really sell it."Availability of moi should increase greatly next year as Cates International starts raising moi commercially in offshore cages. The company is securing permits now, and plans to have the first of a possible four cages stocked in October. The first fish would come to market in early 2001. "We have wholesalers lined up, salivating," says Virgina Enos, vice president of the company.

Other species -- kahala is a prime example -- could be raised in cages as well. The trick is figuring out which ones will take to the lifestyle, Enos says. "A parakeet is very happy in a cage, but a bald eagle is not, and will probably not hatch young there."

Figuring things out is the hallmark of the Oceanic Institute as it enters middle age. The institute's strength is in the way it builds upon research theories and applies them to the real world to create more efficient farming methods with better survival rates, says Charles Helsley, retired Sea Grant director, who oversaw the caged moi project. "It has taken the basic research ideas that have come out of the university and made them user-friendly to the farmer."

A $23 million expansion will create new hatcheries for fish and shrimp, research laboratories and facilities for developing and producing feed for farm-raised seafood.

The institute also has released hundreds of thousands of moi fingerlings into the ocean each year, so that the fish might still be caught the old-fashioned way.

But Farewell emphasizes the future lies in farming, not fishing. "We cannot get anymore fish out of the oceans than we can get today. The only way to get more fish is through technology."

Moi, one of the Oceanic Institute's success stories, is a moist fish with a delicate flavor that shows off well in both simple or elaborate presentations. A fish that’s moi

betta than mostStar-Bulletin staff

Chef Philippe Padovani, of Padovani's Bistro and Wine Bar, says he likes to serve the fish pan-fried or poached, often leaving the skin on, as it is thin, fries crisp and never comes out chewy.

In his restaurant he combines Asian and Mediterranean flavors, using fresh tomatoes, ginger and mushrooms and topping it all with avocado. He will prepare moi a different way at the institute's anniversary gala:

2 pounds moi fillet, in 8-ounce pieces PAN-FRIED MOI WITH

COMPOTE OF BELL PEPPERS

1/4 cup olive oil

Salt and white pepper to taste

Compote:

2 pounds bell peppers (red, yellow and green mixed)

1 tablespoon ground cumin

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

1 tablespoon pommery mustard

1 tablespoon sherry wine vinegar

1/2 cup chicken stock

Salt and white pepper to taste

1 tablespoon chivesTo make compote: Lightly oil peppers and roast or grill until the skin is charred all over. Place in a bowl and cover with plastic wrap until cool enough to handle. Remove skins and seeds. Julienne; set aside.

Heat oil in a pan and add cumin and cumin seed. Add peppers and sweat a few minutes. Add mustard, vinegar and stock. Cook a few minutes, then season to taste. Sprinkle with chives. Keep warm.

To prepare moi: Season each fillet with salt and pepper. Preheat oil in frying pan, then sauté fillets quickly on both sides over high heat. Divide compote among 4 plates; place moi in the center. Serve immediately. Serves 4.

Approximate nutritional analysis, per serving (without added salt): At least 550 calories, 30 g total fat, 6 g saturated fat, 110 mg cholesterol, 150 mg sodium.*

Click for online

calendars and events.