Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Hamakua water KUKUIHAELE, Hawaii -- After 5,000 dead fish, some people might give up.

dilemma: Falls vs.

ranches, farms

Earthjustice seeks to reverse

a Big Isle stream diversion that

will end a catfish projectBy Rod Thompson

Star-BulletinNot Lawrence "Bird" Balberde, who still plans to raise 50,000 Chinese catfish each year near Waipio Valley.

After opponents sought to cut off water for the project, some people might have become grumpy.

Not Balberde, who still cracks jokes as he rigs a toilet float and a tape measure to collect data on water flow to the ponds where he plans to put his fish.

The key to Balberde's catfish project is the little-known Lalakea Ditch and Reservoir near the edge of Waipio Valley. When Earthjustice Legal Defense Fund filed a petition to cut off his water, Balberde discovered he was also on the edge of a controversy.

A retired firefighter and sugar grower, Balberde, now 62, was working for the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism in 1994-95 when he saw business potential in the Lalakea water system.

Built in 1900 to support sugar production, the 6,000-foot ditch feeds into a 35-million gallon reservoir. It was nearly abandoned by 1994, when Hamakua Sugar Co. closed and Kamehameha Schools bought the Lalakea system and thousands of surrounding acres.

The area was a mess, says Balberde's downstream neighbor Richard Mastronardo. "The reservoir was going to the pits. The ditch was full of grass. The road in there, you couldn't even ride it with horses. You had trees on top of trees."

In 1997 Balberde got a year-to-year "license" on 25 acres below the ditch from Kamehameha Schools and agreed to clean and maintain the water system. In 1998 he put 5,000 catfish fingerlings in a floating pen in the reservoir as a test.

Soon afterward he found 500 dead fish. The rest just disappeared. Balberde believes that residual chemicals once used on sugar crops killed them.

He went ahead with plans to bulldoze 30 fishponds below the reservoir, but he let water flow through them without fish for eight months to leach out chemicals.

That's when controversy surfaced.

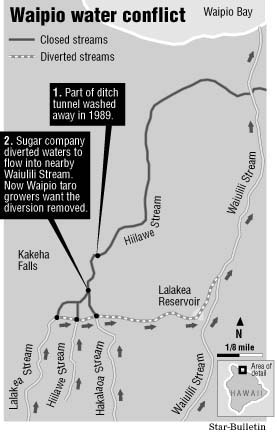

Back in 1989, Hakalaoa Falls in Waipio Valley washed away part of the (better known) Lower Hamakua Ditch where it crossed a cliff face. Hamakua Sugar made a makeshift repair and, to prevent a new washout, illegally diverted water from Hakalaoa Stream to another stream, leaving the falls dry.

Chris Rathbun, a Waipio taro grower and officer in the Waipio Valley Community Association, has tried since 1989 to get the state Commission on Water Resources to remove the illegal diversion.

He says Hakalaoa Falls should be restored for esthetic reasons, and valley taro farms need the water during droughts.

The water commission was slow to act because renewed flow would cut the 24-mile-long lower ditch again and end water flowing to ranchers and papaya, macadamia and foliage farmers on the Hamakua Coast.

Federal money for permanent repairs finally became available this year, and repair work is in the bid process, said state water resources manager Paul Matsuo.The Lalakea system was linked to these problems because it lies upstream from the now-dry Hakalaoa Falls. Believing the Lalakea water had been unused after sugar production ended, Rathbun has tried since 1995 to stop water from flowing into the Lalakea system so it will instead flow into the valley. "Our presumption was there was no use," he said.

Rathbun complained to the water commission against ditch owner Kamehameha Schools. Balberde says he knew nothing about the complaints.

Earthjustice, which represents Rathbun and the Waipio association, recently renewed the complaints against Kamehameha Schools. This time, it got Balberde's attention. A pending Earthjustice petition asks the commission to order Kamehameha "to immediately cease diverting any water."

If Balberde can prove a need for water flowing his way, some water might be restored.

Rathbun says, "If there is a legitimate use, we're willing to share, as long as it doesn't harm the ecosystem." Finding a balance may not be easy.

Balberde said the unlined, leaky reservoir runs out of water in just seven days.

He needs constant flow to his fishponds for cleanliness and aeration.

After passing through Balberde's ponds, water will flow through experimental tea bush plantings, then into a nearby stream.

When rains are good, some water also overflows from the reservoir directly to the stream.

Earthjustice says this is wasting water.

Meanwhile, the weirs that divert water into the ditch also allow some natural flow into the valley in wet weather. The crunch for taro growers comes during drought, Rathbun says.

Kelly Loo, who managed the Lalakea system for 39 years, says springs at the base of the falls provide "more water than farmers need." But there could be problems during drought, he said.

So, the key question is how much water Balberde uses.

The law requires, "Use it or lose it," says Earthjustice attorney Marjorie Ziegler.

Since Balberde hasn't supplied data, there's no proof he's using the water.

That's why Balberde is now taking measurements with the toilet float tied to a tape measure --- to show he's using it.