Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

‘Sensor Web’ key

By Helen Altonn

to future Earth data

Star-BulletinA cluster of satellites working together to monitor the Earth's environmental changes and improve weather forecasting will be operating within three years, NASA scientists disclosed here.

An orbiting "Sensor Web" of data-gathering spacecraft -- some as small as a computer -- is among technical advances planned by NASA to improve planet-side life.

Dr. Ghassem R. Asrar, the space agency's associate administrator for earth science, related the developments at an International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium this week at the Hilton Hawaiian Village.

More than 1,200 scientists worldwide are attending the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers sessions.

Asrar said a constellation of Earth Observing System imagers, led by the flagship Terra and Landsat 7, will make up the first prototype "Sensor Web".

"Our vision is to enable reliable prediction of climate, weather and natural hazards," he said. "We want to see these predictions broadly used to save lives, property and provide economic benefits to the American public and the world."Asrar said NASA technology will revolutionize remote sensing and create enormous economic benefits.

With combined satellite data, for example, it's believed a hurricane landfall can be predicted to within 50 nautical miles in the next decade instead of several hundred miles, he said.

In an interview yesterday, NASA scientists Mark Schoeberl and Peter Hildebrand, with the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., excitedly described plans for the satellite web and other technological advances.

Among them: robotic airplanes to scan hurricanes, microsatellites with global positioning systems to measure temperatures around the globe and new instruments such as wind and air pollution measurement sensors.

Improved forecasts from the new technology will save an estimated $100 billion worldwide, compared with a budget of a couple billion for the earth science portion of NASA, Schoeberl said.

"We will be spending money more effectively and the net benefit will be much greater," Hildebrand said.

The new Earth-observing satellites will work together as a team instead of one satellite doing everything, Schoeberl said, pointing out the present system was created in the 1970s or earlier.

They will be cheap to make and maintain because parts can be replaced by robots and upgraded with newer technology, he said. "If something fails, the whole system doesn't go down."

"The whole concept represents a new way of thinking about space," Hildebrand added, explaining the sensors will be designed to take advantage of other measurements.

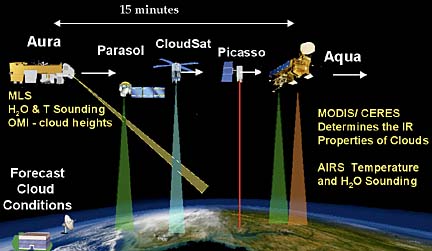

At least four satellites will observe clouds and water vapor in the second sensor web, including the EOS satellites Aqua and Aura, as well as Cloudsat and Picasso.

The Aqua-Aura satellites will be within 15 minutes of each other, forming a super-instrument with combined capabilities, the scientists said.

The webs will range in space from a geostationary orbit to beyond the moon, they said. One will look at the sunny side of Earth and another will look at the night atmosphere in infrared.

A single computer will be 1,000 times too slow to absorb the storm of data by 2020, so it will be fed to teams of computers for crop forecasting, flooding and other models, the scientists said.

Personalized forecasts will be available in home entertainment systems in 20 years, they predicted.

"It's dramatic," Hildebrand said, "but the real intention is to go there ... to produce better systems at costs we can afford with real-life impact on humans."

Added Schoeberl: "We're trying to get away from an adversarial view, that studying the Earth leads to more regulations."

Better predictions about drought, flooding, pollution and other hazards will enable farmers, businesses, agencies and emergency planners to make better decisions, the scientists said.

Pilots want to know about a volcanic eruption and the path of a plume within five minutes, Hildebrand said, noting that now takes days and "accuracy just stinks."

Schoeberl said he was project scientist on a NASA plane that flew into a plume after an eruption in Iceland because the forecast was wrong. Engine repairs cost $2.5 million, he said, adding:

"We're trying to help mitigate such disasters. It's a wise and strategic investment for the United States to work on this stuff."