Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

'My own bias is that all diseases are genetic,

or at least have a genetic component, and

that any information we can gain of one's

genetic makeup will help us identify the

cause and tailor treatment.'

Tim Donlon

QUEEN'S MEDICAL CENTER'S MOLECULAR GENETICS DIRECTOR,

BELOW, SURROUNDED BY DEPICTIONS OF DNA STRANDS AND CHARTS

The promise

of better health

Geneticists at Queen's are increasingly

By Helen Altonn

able to identify those at high risk

for hereditary diseases

Star-BulletinHawaii genetics specialists passed out Good News candy bars labeled "It's a Genome" when the first mapping of the human genetic code was announced last month.

Genetics testing historically was associated with bad news -- a situation that has changed dramatically, said Tim Donlon, molecular genetics director in the Queen's Medical Center's Genetics Center, Hawaii's only comprehensive genetics facility.

In the past, genetics testing was confined to diagnosing a few rare diseases for which there was no cure and little treatment, he said.

Now, he said, causes of common diseases with genetic links can be identified, prevented and treated.

A family history of heart disease prompted Donlon to have himself tested. The finding: He has a double dose of a gene associated with cardiovascular disease and abnormal clotting.

A partially functional enzyme (MTHFR) put him at high risk by causing high levels of an amino acid, homocysteine, in his blood. The level of homocysteine can be reduced by taking folic acid and vitamin B-12 supplements, he said.

He plans to inform his two brothers so they can be tested and treated if they're at risk, too.

"This is just the tip of the iceberg as we are becoming aware of other genetic diseases just like this one," said Donlon, who holds board certificates in cytogenetics, molecular genetics and medical genetics, and has chaired the Chromosome 15 Committee of the Human Genome Project.

"My own bias is that all diseases are genetic, or at least have a genetic component," he said, "and that any information we can gain of one's genetic makeup will help us identify the cause and tailor treatment."

The Genetics Center has been diagnosing prenatal and pediatric diseases and children with birth defects, said director Dr. Berkley Powell, a pediatric geneticist. The mission now is to focus on adult disorders, such as stroke, heart disease, neurological problems and cancer."These are areas where genetics, hopefully, will have an impact in the future, with better understanding of why people get those problems as they get older, Powell said.

"I think the Human Genome Project will do that," he said. "That's what the hype is all about. It's not going to happen tomorrow ... but it's coming.

Genetics staff members include Deborah Schmidt, advanced-practice genetics nurse and reproductive genetics coordinator; Susan Seto Donlon, certified genetic counselor and adult genetic services coordinator, who is married to Tim Donlon; and Janet Brumblay, advanced-practice genetics nurse and pediatric genetics coordinator.

Queen's Genetics Center also includes a Cytogenetics Laboratory, which looks at chromosomes -- "the packaging mechanism by which the DNA or genes are distributed to new cells when cells divide," lab chief Mark Bogart said. (Queen's purchased the lab, formerly Mid-Pacific Genetics Lab, from Bogart.)

Mapping is the first step

Genetic errors or abnormalities can occur in the number of chromosomes, the way DNA is packaged, or specific changes to a specific gene, he said.

Gene makeup also can show which people are more easily affected by environmental factors, such as smoke, he said."We all know people who smoke cigars and cigarettes their whole life and don't get cancer. Then people who live with a smoker get cancer."

Some may be more susceptible to smoking than others because of the enzyme pattern, Bogart said.

Firefighters who learn they're at extra risk from smoke because of their genes could be protected with a special breathing apparatus, he said.

Mapping of the human genome is just the first step, Bogart said. "Now they have to figure out what all the stuff does -- what kind of mutations have clinical significance and which are not significant. It's going to take a long time."

With diseases such as hemochromatosis or iron overload, he said, simple lifestyle choices can be made to enhance somebody's life.

Hemochromatosis "used to be a death sentence," Donlon said, explaining that geneticists could only diagnose the disorder. Symptoms include diabetes, joint pain and cardiac disease, with organ damage leading to premature death.

If a DNA test shows someone is at risk for iron overload, it can be treated simply by donating blood once a month, Donlon said.

Seto Donlon had a patient who thought he had chronic fatigue related to his job. Genetic testing showed he had a double mutation causing an iron overload.

He is worried about potential job and insurance problems but "everybody has something," she said. "We know what he has and his potential is probably better for living a normal, healthy life."

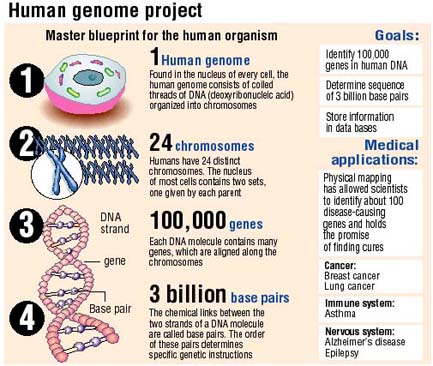

A GLIMPSE AT THE

HUMAN GENETIC CODEThe human body has 100 trillion cells. Each cell (except blood cells) contains the human genome -- all the genetic information necessary to build a human being.

Six feet of DNA are packaged into 23 pairs of chromosomes (one from each parent in each pair) in the cell nucleus.

Each of the 46 human chromo-somes contains the DNA for thousands of individual genes or units of heredity.

DNA in each gene contains four chemical bases that hold recipes for making all organisms. They are: A (adenine), T (thymine), G (guanine) and C (cytosine). A pairs with T and G pairs with C.

Proteins, made of amino acids, are the essential ingredients of all organs and chemical activities. Their function depends on their shapes, which are determined by the 50,000 to 100,000 genes in the cell nucleus.

Source: National Human Genome Research Institute

His genetic information also will benefit his siblings, who can be tested and treated if they have the disease, she said.

When Donlon discovered he was at risk for heart disease, "His original reaction was, 'Oh no, I have this mutation,' " his wife said.

"How could I have it?" he said, recalling his reaction. "I'm testing for all these things."

But, he said, "What could be easier than vitamin supplements or having blood drawn to prevent the disorder?"

Risk assessments can be done for anyone with a personal or family history that shows potential for a genetic disease, Donlon said.

"We can separate risk out by age and give it to the physician as a guide," said Seto Donlon, who also is a consultant at Tripler Army Medical Center. For instance, screening begins at age 25 for certain hereditary forms of cancer, she said.

She said many physicians believe genetic diseases are rare and they don't understand patients can be tested for genetic predisposition toward a disease.

"They don't know the questions to ask. We're trying to tell them questions, to educate ... We're also appealing to the public to look out for themselves," she said, urging people to discuss their family history.

The Genome Project, which mapped more than 90 percent of human DNA, will accelerate discovery and effects of genes that cause disease, she said. "It has forced society to take a look at this. A lot of people, physicians, have ignored the technology."

Who gets the information?

Risk assessments most often are done for breast cancer but are increasing for colon cancer and hemochromatosis, Seto Donlon said.

Tests also are given for hereditary cancer, neurogenetic diseases, thalassemia and leukemia. Thrombophilia, involving blood clotting, is another major genetic disease that can be detected, the geneticists said.

"We're focusing on diseases in which we have treatments or preventions," Seto Donlon said.

A $250 fee is charged for a test and consultation, with a $75 reimbursement from the Hawaii Medical Service Association.

Fear is the biggest barrier, Seto Donlon said, noting that the main question from callers is, "Who is going to get the information?"

Only the patient gets the information, she said.

Powell said people are split about 50-50 on whether they think mapping of the human genome is good or bad.

"They're worried about probing too deeply into our humanness," and they're afraid the information will be used against them for insurance, their job or in some other way, he said.

Even he's a little apprehensive, Powell acknowledged: "I'm not sure that we're not going to see some serious negative repercussions."

There are some big challenges, he said."We will have to be more management-oriented. We will have to understand interactions of inherited and environmental components and, though we're family-focused, we have to strive harder to provide for individual confidentiality."