Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

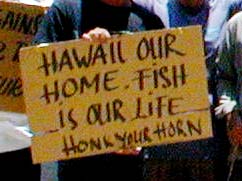

Many fishermen who consider

Hawaii their home say they were

caught off guard by

an unfair rulingTimeline of longline

By Peter Wagner

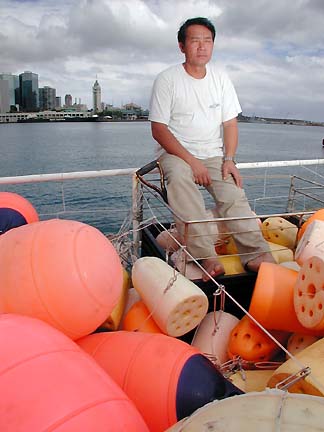

Star-BulletinLIFE has been good for Cung Nguyen since he arrived in Honolulu on a Gulf Coast longliner eight years ago.

Except for a deep scar on his left hand where a heavy-duty fishing line burned through his leather glove, the 48-year-old fisherman is healthy and quick to smile.

"From here, I can walk to Chinatown and to my house," said Nguyen, who lives on School Street and works on the 70-foot longliner King Fisher. "The weather is just like Vietnam."

His steel-hulled boat was tied up this week at Pier 17 in Honolulu Harbor, home to about 50 boats owned by Vietnamese Americans who dominate Hawaii's longline fleet.

Nguyen and his tightly knit community of fishermen are in consternation over a judge's order that in two weeks could shut down 6.5 million square miles of ocean and wipe out their investments. With homes and families in Hawaii and a huge financial stake in the surrounding ocean, fear and helplessness prevail.

"I'm scared," said Nguyen.

Judge David Ezra on June 26 expanded an earlier restriction on tuna and swordfish longline fishing, pending an environmental study on threats to endangered sea turtles. The judge in December had closed 1.5 million square miles of prime fishing grounds north of Hawaii after two mainland environmental groups sued the National Marine Fisheries Service for failing to protect endangered sea turtles.The Hawaii Longliners Association and fisheries service have asked the judge to reconsider his order before it goes into effect July 26.

Some 50 Vietnamese American longliners currently operate out of Honolulu Harbor, the largest contingent in the state's fleet of 119. Korean Americans make up the next largest group with about 40 boats, followed by the "poi dogs," a mixed group of local and mainland fishermen operating about 25 boats.

Like the Korean Americans clustered at Kewalo Basin, the Vietnamese of Honolulu Harbor struggle with a language barrier that has left them oddly estranged in a drama that threatens their livelihood.

"We can't speak for ourselves," said Nguyen.

Many were at sea when Ezra's most recent ruling shocked the fishing industry. None was aware of the lawsuit that led to the closures."We weren't part of the process," said Timon Tran, a former boat owner and spokesman for the Vietnamese fishermen.

Chin Choe of the Hawaii Korean Fishing Association said fishermen at Kewalo Basin don't understand the situation or know what lies ahead.

"They don't know what went wrong," he said.

Among their questions: Why are Hawaii longliners banned from international waters where much larger Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese fleets are free to fish?

Industry grew despite economy

Rocking forlornly at Pier 17 this week was the Blue Fin, rusty and boarded up for more than a month. In light of the judge's decision, the owner, Liet Lu, doesn't want to invest $40,000 to fix the boat."I think I am going to lose my job very soon," said Lu, a 22-year Hawaii resident with four children, one of them entering medical school.

Both Nguyen and Lu fled Vietnam after the fall of Saigon in 1975. Nguyen, like many refugees, ended up on a Gulf Coast shrimp trawler before joining the migration to Hawaii's relatively untapped fisheries about ten years ago.

Lu came to Hawaii in 1978. He cleaned toilets, drove a cab and did other menial jobs until -- with the help of family and friends -- he bought a Louisiana trawler.

The arrival of two Vietnamese longliners in 1988 led a migration from the Gulf and mainland coasts that more than tripled Hawaii's fleet from 37 to 141 in four years. Likened to the California Gold Rush, the westward movement was drawn by healthy reserves of tuna and swordfish, and by the encouragement of federal and state agencies.

The flurry brought new rules regulating tuna and swordfishing in waters around Hawaii, a permit system with a cap of 164 licenses, and clashes with local fishermen that still simmer.According to Michael Travis, a National Marine Fisheries Service researcher who last year published a detailed account of Hawaii's longline fishery, the fisheries service in the mid-1980s helped former Gulf trawlers convert to longlining. The state Department of Business and Economic Development, meanwhile, was working to expand Hawaii's fishing industry and find new markets for locally caught fish.

With the exception of coastal fishermen, the new arrivals were welcomed with open arms. Commercial fish landings went from 13.7 million pounds in 1986 to 37 million pounds in 1998.

"One of the bright spots during the economic downturn in this state in the past decade has been this very vibrant fishing industry," said Craig MacDonald, ocean resources branch manager at the Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism.

Todd Steiner, director of the Turtle Island Restoration Network, one of the two plaintiffs in last year's lawsuit, is sympathetic to the fishermen but says sea turtles -- particularly the endangered leatherback -- must be saved.

He notes that while longliners have been in Hawaii for decades, the industry grew on a recent influx of mainland fishermen.

"It's not like we're destroying a 100-year-old industry," Steiner said. "This is a new fishery. Most of these boats weren't there 15 years ago."

Hawaii fishermen will stay

Though Ezra's order could force an exodus, none of Hawaii's fleet is inclined to leave."Hawaii is our home," said Tran, a 25-year resident of Hawaii and among the first to operate a Gulf coast longliner here. "Why should we move?"

Tran noted that it cost $30,000 to bring his trawler to Hawaii nine years ago. Another upheaval, he said, would be costly and uncertain. Meanwhile, boat owners have families, mortgages and other commitments in Hawaii.

"I'm very proud to be a Hawaii resident and a kamaaina," Tran said.

Jim Cook, chairman of the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council and a pioneering Hawaii longliner, said Hawaii's longliners are here to stay.

"With very few exceptions, everyone in this fleet is a resident of Hawaii," he said. "These people are homeowners and taxpayers."

Steve Gates, owner of the 82-foot longliner Miss Lisa, roamed the Atlantic from the Grand Banks to South America. But he said he found a home in Hawaii. VOICES

Chin Choe

MEMBER, HAWAII KOREAN

FISHING ASSOCIATION

"(The Kewalo basin fishermen)

don't know what went wrong."

Liet Lu

OWNER AND CAPTAIN OF BLUE FIN

"I think I am going to lose my job very soon."

Steve Gates

OWNER OF MISS LISA

"In Honolulu, everyone has to return to port.

Every time I'm in port, I'm home

with my wife and kids.""In Honolulu, everyone has to return to port," he said. "Every time I'm in port, I'm home with my wife and kids."

Gates, who has a son at Kailua High School and a daughter at a mainland college, estimated he's put $5 million into Hawaii's economy in the past nine years.

"That's about how much I've grossed and I haven't kept much of it."

At Kewalo Basin, where many Korean-American longliners are docked, anxiety runs high.

"We work very hard half our lives here and now they tell us we have to leave," said Linda Lee, whose husband, Shinsoo Lee, owns two boats, one of them captained by his son, Tim.

"I lived here almost all my life," said Tim, who at 28 is one of the youngest captains in the fleet. "My daughter was born here. I went to school here. And now they tell me to pack my bags and leave. I'm a local. I'm not a foreigner."

Meanwhile, at Pier 17, Nguyen continued to hope while Lu scraped away at the rust on his boat.

Nguyen gestured to $200,000 in longline gear neatly stowed on the deck of the King Fisher.

"It's not that easy," he said. "Where can we go?"

Ironically, he said, turtles are considered bad luck among Vietnamese fishermen and any encounter is a sobering experience.

"We don't want it," said Nguyen. "It's bad luck for us."

LONGLINERS were here in Hawaii long before fishermen from the Gulf of Mexico and the coastal United States more than tripled the fleet ten years ago. Timeline of longlining in Hawaii

The early pioneers evolved from wooden tuna sampans that fished Hawaii's waters with poles. Dragging hooks on rope and keeping within 20 miles of shore, the fleet gave way to bigger boats, miles of monofilament line and a $50 million tuna and swordfish industry.

The new arrivals built Hawaii's fleet from a core of about 37 boats in 1987 to 141 in 1991. Here's how it happened:

1970s: 14 longliners in the Hawaii fleet.

1983: Fleet grows to 30, built on the conversion of lobster and bottom-fish boats.

1987: 37 boats.

1988: First two longliners arrive from Gulf Coast.

1988: Fleet grows to 60 longliners, fed by migration of Vietnamese Americans from the Gulf.

1989: Swordfishing begins north of Hawaii, drawing new arrivals from the East Coast.

1989: 80 boats.

1991: Fleet reaches a high of 141 boats -- a mix of Gulf, Alaska, West Coast, East Coast and local fishermen.

1991: Moratorium on fishing permits.

1994: Ceiling of 164 permits established.

1999: Fleet stabilizes at 119 boats.

Source: National Marine Fisheries Service