Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Saturday, July 1, 2000

Hawaii's blended population

By Susan Kreifels

rejected eugenics movement

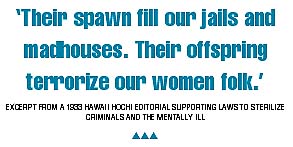

Star-BulletinThey form a class of subnormal citizens in which crime and disease are the rule rather than the exception," a 1933 Hawaii Hochi editorial said in favor of bills to sterilize vicious criminals and mentally ill. "Their spawn fill our jails and madhouses. Their offspring terrorize our women folk."

Recent research uncovered a Vermont eugenics plan in the 1920s and 1930s that led to the sterilization of several hundred poor people, Indians and others deemed unfit to procreate. More than half of the states passed similar sterilization legislation during that time, historians say.

But despite several attempts by territorial legislators to follow that tide, the islands didn't go along with the eugenics movement, which later lost favor as Nazi Germany began its campaign of extermination against Jews.

The Hawaii bills, according to news reports at the time, would have forced the sterilization of the "unfit" such as the insane and "feebleminded," violent criminals, sexual psychopaths, and epileptics. Advocates believed such problems were hereditary and that the legislation would protect the public and save the territory millions of dollars supporting such people in institutions, including students in industrial schools.

Supporters over the years, according to the reports, included Hawaii's Territorial Medical Association, social workers, the prison's board of directors, Republican women's groups represented by Princess Kalanianaole, Gov. Lawrence Judd, and the Hawaii Hochi, a leading Japanese American newspaper founded and published by Fred Makino, known as a fighter for social justice.In 1937, a territorial grand jury also recommended that legislators pass laws requiring the sterilization of "mentally deficient people."

John Stephan, a history professor at the University of Hawaii-Manoa, said the eugenics movement was international and crossed racial, political and economic lines.

"It's not that conservatives were for it and liberals against it," said Stephan, who is researching Makino's work. The Hawaii Hochi, for example, defended sterilization as a way to protect women and children from sex crimes, which were making news at the time.

But Stephan said he can't imagine such a bill ever passing in Hawaii. "It would exacerbate feelings and create social tensions," he said.

"That was not in the interest of the oligarchy, which wanted a smooth, harmonious, paternalistic society with a mild and obedient working class."

Sketchy reports said legislators were concerned about the controversy such moves would raise and, in the early 1920s, also questioned their constitutionality. The U.S. Supreme Court, however, upheld sterilization laws in 1927 when the court said "three generations of imbeciles (in one family) are enough."

Hawaii baffled international eugenicists, whose worst nightmare was interracial marriage. Yet the islands appeared a place of little racial tension.

"The oligarchy dominated affairs, both social and political," said Paul Hooper, chairman of American Studies at UH-Manoa. "They were talking about Hawaii as a model for ethnic harmony."

Pauline King, professor of Hawaii history at Manoa, said the islands were still heavily influenced by Christianity. Eugenics legislation "would still have to come up against that Christian feeling, no matter how popular it might have been," King said.

And Dan Boylan, a political historian at UH-West Oahu, said some legislators probably had family victims of Hansen's Disease who were sent to Molokai. "A large section of the population was ostracized and ultimately expelled," Boylan said. "Many people were fearful and hiding in the hills."

Helen Chapin, a Hawaii Pacific University vice president emeritus who specializes in the history of Hawaii's newspapers, said that attitudes brought into Hawaii by a growing military population, plus increasing U.S. patriotism generally, could have stirred some support for eugenics legislation.

"Nobody knew what to do about Hawaii," Chapin said. "Powerful whites were marrying well-to-do Hawaiian women."

The alleged beating and rape of a white Navy wife here by five "local boys" -- two Hawaiians, two part-Hawaiians and one person of Japanese ancestry -- in the 1931 "Massie Case" received national attention. After a trial ended in a hung jury, a defendant was shot to death by the victim's husband, mother and two other Navy men.

Chapin said eugenics laws probably would have targeted non-whites and the poor because they had greater numbers in the institutions.

The eugenics movement -- improving the human species by mating for certain traits -- gained strength in the United States after World War I when victorious Americans held "fitter family" contests at state fairs, awarding families with the "best stock and pedigree" like they did livestock.

"People were talking about maintaining the national strength, which made a very convincing argument for maintaining the reproductive strength as well," said Philip Wilson, a history of science professor at Shimer College in Illinois and visiting professor at UH-Manoa in 1992-93.

Wilson, a eugenics researcher, said listed people considered "social deviants" included criminals and the insane, the homeless, blind and deaf. Numbers of sterilizations range from 40,000 to 200,000 men and women, some in their middle-teens. Most were performed in institutions on poor Caucasians.

Wilson said eugenics in the United States could be viewed as racist: empowering wealthy Caucasians of Northern and Western European heritage by promoting more children from them, less from others.

The movement was led by the Eugenics Record Office with support from the federal government and Carnegie Foundation. Its director, Harry Laughlin, envisioned a new world government where most control would be in the hands of countries with the "best stock." Laughlin had political clout and helped shape tougher U.S. immigration policies that denied entrance to "social deviants," particularly from Southern and Eastern Europe, Wilson said.

Laughlin also took his ideas to Germany, influencing the selective sterilization of Jewish people, Wilson said. As the world became more aware of Nazi activities, the office closed in 1939-40. After World War II, states started to rescind their eugenics laws, and today Wilson is not aware of any left.

Hawaii puzzled eugenicists, Wilson said. At their 1921 international conference, research papers looked at Hawaii's growing "hybrids," or mixed races, but noting that "probably nowhere in the world is there a lesser amount of racial strife and antagonism."

"Hawaii was a mystery," Wilson said. "It seemed to be different from what they found in the continental U.S."

Photos of "very beautiful Hawaiian women" were compared with children of mixed marriages. "They were trying to argue a diminishing element of beauty from what they called the pure Hawaiian. However, they didn't make any recommendations."

Why some states and territories didn't pass eugenics laws remains "unwritten history," Wilson said, calling protesters a "very quiet group" that included religious people who considered sterilization a form of birth control.

In Hawaii, according to reports at the time, the main arguments for forced sterilization were economic and safety issues. In 1923, the Republican women's auxiliary club unsuccessfully pushed legislation that would sterilize men convicted of violent sexual crimes or attacking girls under 12.

In a 1932 report, Dr. Nils Larsen, director of Queen's Hospital and a leading advocate, said mentally deficient people reproduced at a terrific rate, causing enormous economic burdens on the state.

But Dr. Howard Clarke told the Honolulu County Medical Society that "passing discriminatory laws against our largest class of population (poor) is dangerous business...The well-to-do who have benefited as much from the labors of the poor now want to avoid paying the price of poverty." Clarke also said the support of many unmarried women to "neuterize the male is remarkable."

Larsen said sterilization was not directed against the poor. "The ditch digger is capable of having just as intelligent children as the bank president," Larsen said.

Sen. Harold Rice introduced sterilization bills in 1932 and 1933, the second one recommended by Gov. Lawrence Judd, according to reports. Louis Warren from the board of prison directors sent a letter to civic leaders saying opponents "either do not understand the condition or who hold to personal ideas of personal rights and liberties or the sacred right to beget children regardless whether the offspring be good or bad and regardless of the welfare of the public at large."

Forced sterilization issues continued for years. In 1940 Catholic leaders investigated reports of indigent married women with at least four children who were told they could get no more free hospitalization unless they were sterilized. A blind person told legislators in 1961 that he was forced to undergo the procedure in 1940 by the former Bureau of Sight Conservation. Sterilization bills were introduced as late as 1970.

Historian Boylan says he's not surprised eugenics legislation never passed here.

"Can you imagine someone going into a synagogue in Honolulu and shooting it up?" Boylan asked, believing the multiethnic community here is more tolerant than the mainland.

"This is a peaceful place. People are better to each other here."