Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

America at last honors 22

Asian-American heroes with the

nation's highest award

for valor in combatBy Gregg K. Kakesako

Hawaii's surviving soldiers receive their due

SPECIAL SECTION

Today's recipients

Star-BulletinWASHINGTON -- Army Chief of Staff Gen. Eric "Ric" Shinseki, the country's highest-ranking Asian-American officer, today said the 22 newest Medal of Honor recipients are finally getting "overdue recognition."

Shinseki, a former Lihue resident, told the Star-Bulletin today that "those of us who grew up in Hawaii have heard of the exploits" of the segregated Japanese-American 100th Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

"I think it is a magnificent recognition of men who are part of the legends and history of our country," said the four-star general, whose uncles fought in combat in the 100th Battalion.

Shinseki and Army Secretary Louis Caldera were among the special guests at several Army functions that preceded this afternoon's Medal of Honor ceremony.

SPECIAL REPORT

Recalling the strength and honor

of Hawaii's World War II veterans

They also attended a special Army luncheon for 100th/442nd veterans and their families, patiently posing for pictures and listening to the old soldiers tell their stories.During a special memorial service at Fort Meyer's Memorial Chapel, Shinseki sat next to U.S. Sen. Daniel Inouye. Hawaii's senior senator was recommended for the Medal of Honor during World War II but received the Distinguished Service Cross instead.

Inouye is one of the 22 soldiers who will be privileged to wear the nation's highest medal of valor after today.

One of the speakers at today's memorial service was Punahou School chaplain David Turner, grandson of the late Col. Farrant Turner, the first commander of the 100th Battalion. He compared the intertwining lives of the men of the 100th/442nd to the interweaving branches of Hawaii's hau trees.

"It's hard to distinguish where one ends and the other begins."

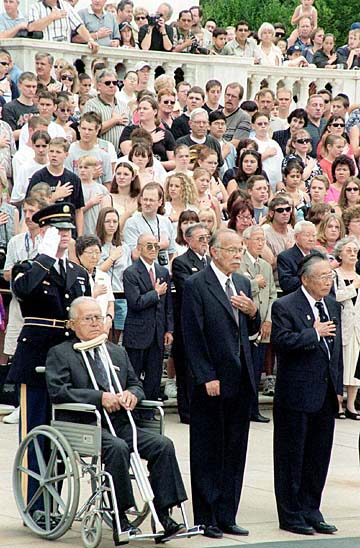

At Arlington National Cemetery this morning, three awardees -- Waianae resident Yeiki Kobashigawa, George Sakato of Denver and Rudolph Davila of Vista, Calif. -- helped lay a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknowns.Kobashigawa, one of the original members of the 100th Battalion, needed to be assisted during the wreath-laying ceremony, since he is still bothered by shrapnel from an old war injury.

Before today's ceremony Inouye noted that it is hard to single out any single moment in his long career. "Who's to say which part of my life is greater than any other," said Inouye, who has received numerous accolades for public service that has spanned nearly half a century.

The 75-year-old said he still considers a certificate he was awarded as a Junior Police Officer at Lunalilo Elementary School one of his most treasured mementos."There is no greater honor than to be elected and to serve," said Inouye, who was first elected to the Hawaii Territorial Legislature in 1954 and became the new state's first congressman four years later.

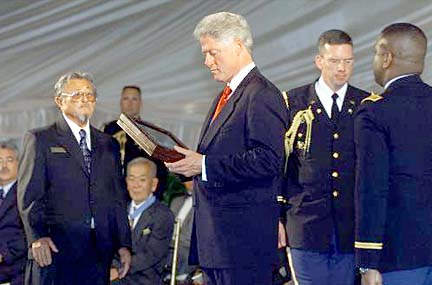

But when he receives the Medal of Honor at the White House today, that will mark the high point of his military career. "You don't get any higher than that."

When speculation began several months ago over the possibility that the Distinguished Service Cross he earned during the last 12 days of the European campaign might be upgraded to the Medal of Honor, Inouye said he did not pay much attention.

"But when the secretary of the Army called, I was speechless. I couldn't think of anything to say except 'Thank you.' ... The feeling was overwhelming."

Inouye said the movie "Saving Private Ryan" realistically portrayed the horror of war."It was because of the way the Normandy landing was described down to details of bullets zipping into the water. Up until then, the only war movies I watched were the unreal 'Rambo' stuff -- things I knew didn't happen. When I finally saw the movie, it was the real McCoy.

"All of us in combat experience so many things in common. We were afraid. Anyone who says otherwise is a fool."

Even as he receives the nation's highest tribute to combat soldiers, Inouye -- who lost his right arm on a Italian battlefield -- said all those who served "demonstrated courage above and beyond the call."

More than 16 million went to the battlefield in World War II. Only 442 ended up with the Medal of Honor.

Inouye asked, "Who is to determine why that man deserved a medal and why this one didn't?

Referring to the 100th/442nd, Inouye said today's honors belong to all the soldiers who charged the enemy in the French Vosges Mountains.

"I had to have the support of so many of them. No one can take out a machine gun nest without support."

All 22 new Medal of Honor recipients will be inducted into the Pentagon's Hall of Heroes tomorrow afternoon.

Hawaii’s surviving soldiers

They were mature beyond their years,

receive their due

tempered by what they had been through,

disciplined by their military training

and sacrifices ... They stayed true to their

values of personal responsibility,

duty, honor and faith.

-- From "The Greatest Generation" By Tom BrokawBy Gregg K. Kakesako

Star-BulletinWASHINGTON -- They were unassuming men who rose from similar, simple island backgrounds.

Today 22 aging warriors finally get long-overdue recognition with the nation's highest tribute -- the Medal of Honor -- for heroism in combat more than five decades ago, in World War II.

Only seven of the former soldiers will be able to attend this afternoon's White House ceremony, where President Clinton will hang around their necks the sky-blue ribbon that dangles a gold star and the word "Valor." Ten died in the battle action for which they are being honored. Five died since then, still awaiting their final recognition.

Of the seven survivors, five are nisei -- second generation Japanese Americans -- from Hawaii.

The Army last month, more than a half century late and at the urging of Hawaii Sen. Daniel Akaka, decided to upgrade the recognition of 22 Asian and Pacific Americans. Twenty were members of the famed segregated Japanese American 100th Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Four years ago Akaka pushed through legislation requiring the Army to determine whether Asian and Pacific Island Americans who received the Distinguished Service Cross had not been properly recognized because of the war's anti-Japanese sentiment. Many of today's recipients were initially recommended for the Medal of Honor, but received instead the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation's second-highest medal for valor.Akaka noted that despite the fact that 25,000 nisei soldiers fought in Europe and the Pacific under "fierce and heavy combat," only one nisei was awarded the Medal of Honor after the war and then only after congressional intervention.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes on the West Coast and imprisoned behind barbed wire in relocation centers. They were originally classified "4-C," or "enemy aliens," by the U.S. government.

But the nisei volunteered in droves to serve their adopted country. They went on to earn 18,143 decorations, including 52 Distinguished Service Crosses, 560 Silver Stars, 22 Legions of Merit, 4,000 Bronze Stars and 9,486 Purple Hearts in eight campaigns.

Their losses included 649 killed in action and 67 missing in action.

Today's Medal of Honor recipients join a very exclusive organization. Of the 441 Medal of Honors awarded during World War II until this point, only 58 of the soldiers survive today. Over time, in all U.S. armed conflicts, a total of 3,430 Medals of Honor have been awarded before today.

Here are their stories:

FOR decades, none of Yeiki "Lefty" Kobashigawa's family was aware that the unassuming nisei warrior was an extraordinary soldier and leader of men.

Yeiki Kobashigawa

'I wanted to represent my family

in the American army'In 1980 his youngest granddaughter visited Washington, D.C., and took in an exhibit in the Smithsonian Institution on the American Japanese Experience and the 100th Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

There, on a plaque, were listed Kobashigawa's deeds on June 2, 1944, when he and his companions destroyed four German machine-gun nests and earned the Distinguished Service Cross.

When his son, Merle, asked him about it, the Waianae resident just said, "It was something he had to do."

"My father said they were pinned down ... whenever anyone stuck their head up, they would get blown away. That was it."Kobashigawa, 82, was born in Waiakea on the Big Island and never got beyond the seventh grade at Waianae Intermediate and High School after his family moved to Oahu.

"I had to quit because of my dad's kidney illness and had to help him all the way," Kobashigawa said. "This was very common at the time. Parents expected ... to have an extra hand helping."

Kobashigawa said his nickname, "Lefty," comes from his baseball-playing days with Waianae Plantation Company and the Rural Japanese Leagues.

Throughout his youth Kobashigawa worked days for the plantation, then went home to help in the family truck farm.

After registering for the draft, Kobashigawa was inducted on Nov. 16, 1941. He was 18. "The plantation manager was upset because at the time all the plantations had a lack of men, so I could have gotten a deferment. But being from a family of nine, someone had to represent the family. I felt that's the reason why I didn't tell him I was going to the draft board. I wanted to represent my family in the American army."

On Dec, 7, 1941, Kobashigawa, then assigned to the Hawaii Army National Guard's 298th Regiment, still didn't know how to load his rifle. He was home in Waianae on leave, preparing for a Sunday baseball game, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

"I caught an Army truck which took us through Kolekole Pass back to Schofield ... but shortly after that, they took away our rifles. I don't know what they thought we would do."

SHIZUYA "Cesar" Hayashi, 82, never completed Andrew Cox High School in Waialua. He left in the ninth grade to help out on his family's pig farm.

Shizuya ‘Cesar’ Hayashi

'Things happened so fast

that now it seems so crazy'Drafted in March 1941, Hayashi picked up the nickname Cesar "because my sergeants couldn't pronounce Shizuya. I guess Cesar is closest they could get to Shizuya. But my friends still call me Cesar today."

On Nov. 29, 1943, Hayashi missed the warmth of the island sun. It was nearly noon and getting colder as his unit was on patrol near Cerasuolo, Italy.

"I really didn't know where we were. I remember it being mountainous, with the Germans always looking down on us. That's why there was always a lot of casualties.

"The Germans always were so well camouflaged. Then there were the 88 mm cannons, the 'screaming meemies' ... that took out a lot of the boys, catching them in the back."

Hayashi was outfitted with the Army's Browning Automatic Rifle, commonly known as the BAR and one of the most powerful weapons in the war, when he charged a German machine-gun nest, firing the rifle from his hip. "Things happened so fast that now it seems so crazy."

He took out the German machine gun nest, killing seven men in the nest and two more as they fled.

The Germans then opened fire on him with an anti-aircraft gun. Turning the BAR on the anti-aircraft pit, Hayashi killed nine of the enemy, taking four prisoners and forcing the remainder of the force to withdraw from the hill.

At one point Hayashi recalls facing an armed teen-aged German soldier. "He was crying ... holding up his burp gun ... but I couldn't shoot him ... I just told all of them to get up."

As they surrendered, Hayashi said one of them had an Iron Cross -- which he took to remind him of that encounter.

BECAUSE Barney Hajiro, 83, liked to fight so much, Army officials sent him to a rifle company in the 442nd Regimental Combat's 3rd Battalion after he was court-martialed for his second brawling offense.

Barney Hajiro

He kept getting into fights, so they

sent him to a rifle companyHajiro had gone to the aid of another nisei soldier in the Leghorne, Italy, during a break in the action. "It was late at night. I was singing, coming home when I saw this soldier in trouble. He was being beaten up by a bigger guy, so I jumped in. I don't know who he was since he ran away and I was left alone. There was no one there to back up my story.

"The sergeant tells me: 'Barney, you're fighting again and since you like to fight so much I am sending you to a rifle company -- I Company.' "

Hajiro said he was issued the 21-pound BAR and given a week to learn how to use it.During the rescue efforts for the Texas 36th Division's "Lost Battalion" in the Vosges Mountains of eastern France, most of the sergeants in his company had been wounded. By mid-afternoon on Oct, 29, 1944, Hajiro was in the midst of what was called "the Banzai Charge." Some accounts say Hajiro may have been the man who started the assault.

"There was shooting coming from all sides. I got hit in my arm ... my BAR was hit ... and then my helmet was blown off my head."

By the time Hajiro overran the enemy he had destroyed three machine-gun nests, but an enemy bullet had penetrated his left wrist and severed a nerve. Another bullet had entered his shoulder. His left cheek also was scarred by an enemy bullet.

Earlier in the war, Hajiro was cited for the Distinguished Service Cross on two other occasions. One was for neutralizing a stone house held by the Germans at Bruyeres; the other was later, in Belmont, for taking out a German patrol, killing two and taking 15 others as prisoners.

Hajiro was the eldest of nine children and left the 8th grade at Puunene on Maui to work in the sugar-cane fields for 10 cents an hour, 10 hours a day. Because he had to leave school to help support his family, Hajiro, an aspiring track star, was never able to pursue his dream to compete in high school and college.

ON Dec. 7, 1941, 17-year-old Daniel K. Inouye, who had taken medical aid training in his ambition to become a doctor, was pressed into service handling civilian casualties from the attack on Pearl Harbor. By March 1943, his freshman pre-medical studies at the University of Hawaii were interrupted when he enlisted in the Army.

Daniel K. Inouye

'I hope to receive (the medal)

on behalf of the men in my platoon'As a patrol leader in the "Go For Broke Regiment," Inouye won a Bronze Star and a battlefield commission after two weeks of bloody fighting in the French Vosges Mountains rescuing the Texas battalion that had been surrounded and cut off by the Germans.

In discussing the events leading to the Italian battle for which Inouye was to eventually win the Medal of Honor, Hawaii's senior U.S. senator noted that "for every recipient of any medal, there are hundreds who are equally deserving but who were not recognized.

"When I receive this medal, I hope to receive it on behalf of the men in my platoon. They all deserved it."

In assaulting a heavily defended hill in Italy 12 days before the war ended on May 2, 1945, Inouye was wounded in the stomach, but continued to lead an assault on a machine-gun nest. With his right arm shattered by a German rifle grenade, Inouye threw his last grenade with his left arm before being knocked down by another bullet in the leg.

In taking out three machine-gun nests, Inouye is credited with killing 25 German soldiers and capturing eight. At the time, many believed that the only thing that prevented him from getting the Medal of Honor was because he was Japanese.

Inouye spent 20 months in an Army hospital before returning home. He began serving in island politics in 1954 after obtaining a law degree from George Washington University Law School. When Hawaii became a state in 1959, Inouye was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, then to the U.S. Senate in 1962.

WHEN Yukio Okutsu returned home in December 1945 all he had to show for his 18 months in combat was a toilet kit of personal items, including his Distinguished Service Cross.

Yukio Okutsu

He still has coffee once a week

with buddies from Company F"The Army lost my duffel bag, which contained all my clothes and a couple of wartime souvenirs, including a pair of German field artillery binoculars," said Okutsu, 78.

Okutsu also gave up that Distinguished Service Cross a few years ago when a close friend from Company F, George Kawakami, asked him to loan it and a photo of a 23-year-old Okutsu receiving the award to the Kauai Museum. Okutsu was born and raised in Koloa.

Now every Thursday, Okutsu, who moved to Hilo after the war, still meets with his 442nd F Company "coffee gang" at Cafe 100 "to talk story and drink coffee." The group used to be larger and meet several times a week until Hoxie Nagami died. It's now down to Okutsu, Sadao Nishida, Wataru Kohashi, Robert Honda and Herbert Akana.The conversation over cups of coffee for the past two decades sometimes would turn to Okutsu and whether he would receive the Medal of Honor. "I knew they were going to upgrade some of the medals, but I didn't know if I was going to be in there ... I never thought about it. What the heck, we're too damned old already."

Okutsu, the fourth of 11 children of Chozuchi and Otoshi Okutsu, volunteered for the 442nd RCT in 1943 because he didn't want to stay in Koloa and work in his father's manju store. Although he has returned to Kauai many times over the years to visit with family who still live there, Okutsu said there has never been a family reunion since the war. The first -- which will gather family members from Maui, Oahu, California and Nebraska -- will take place at Koloa this summer.

After the war Okutsu attended a watchmaking school in Kansas City, worked on the federal cleanup of Bikini and Eniwetok and then worked for Hawaii County as a mechanic until he retired in 1985. He and his wife, Elaine, now tend to an acre-and-a-half anthurium farm.