Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

A visiting mayor

By Burl Burlingame

compares his historic

town with ours

Star-BulletinWE'RE used to our city. It is the frame for our experience, the horizon line for our landscape, the everyday environment that becomes polished into invisibility through repeated experience. That's why traveling is so much fun; the average becomes fresh.

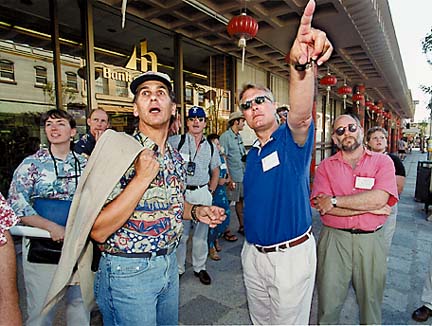

City officials, though, are supposed to pay attention to the orderliness of the everyday environment. That's why, during a recent conference sponsored by the Historic Hawaii Foundation, we followed Len Weeks around as he toured Chinatown, just to hear about our own back yard.

Weeks is mayor and commissioner of St. Augustine, technically the oldest Western-style city in the Americas, an isolated enclave of 12,000 citizens who host 3.5 million drive-in tourists a year. These tourists sample the town's historic architecture, eat in its developing restaurants and largely blow out of town by nightfall because hotels are rare. Tourism is confined mostly to the weekend, and 75 percent are Florida residents, although business travelers are on the upswing, and that means more expense-card restaurant meals and midweek hotel bookings.

"And 40 percent of the property is non-taxable!" said Weeks.

St. Augustine will have a twin city soon, a 25,000-inhabitant metropolis 10 miles away with the classy name of World Golf Village, now under construction.

Weeks was supposed to have been escorted through Chinatown by his royal tourguideness himself, Mayor Jeremy Harris, but Harris was attending Judge Martin Pence's funeral, and Emergency Services Department head Salvatore Lanzilotti was appointed instead. Lanzilotti has worked with Harris since 1988 and is the city's volunteer liaison with Chinatown's merchants.

Also tagging along were Weeks' wife Kristy and a dozen historic-preservation students.

One substantial difference between the two historic cities is the many-tiered income-level housing and hidden utility and parking complexes in Chinatown.

"What's the water level here?" asked an astounded Weeks. "In our city it's 3 feet down."

"It's like that here," said Lanzilotti. "Gray lava rock, a builder's nightmare."

"Oh, we're on sand," said Weeks. "When we dig, the hole falls apart."

The group was led into an underground parking lot beneath low-income housing, the turn-arounds hiding electrical utilities for the block. "Wow!" said Weeks. "Compact. No wasted space."

The group moved to a sidewalk widened with imitation ship-ballast stones. "Chinatown teems with activity, and the merchants traditionally put their goods outside the stores," said Lanzilotti. "If the sidewalks aren't wide enough, pedestrians get pushed out onto the street. And that's why we encourage awning and trees, to make it more pleasant."

"Every city in the country is trying to become more walkable," said Weeks. "Were there trees here originally?"

"Not really, and that's an interesting historic-preservation dilemma," said Lanzilotti. "Chinatown never had trees -- but that was because it was a marginal area in the 1800s. The area wasn't rich or important enough to those who ran the city to bother. But if people had cared about Chinatown a century ago, we believe they would have planted trees."

"We have a streetlight dilemma," said Weeks. "There were fewer lights in the past, but if you put more in, it's not accurate. But if the area isn't lit well at night, people won't go downtown because they don't feel safe. You want to keep the vibrancy, without losing the charm, soul or identity of the community."

"Exactly," said Lanzilotti. "We added more lights, and Chinatown goes from an eight-hour day to a 16-hour day. It's more productive, and safer. Plus a new police station. It's safer now than Waikiki."

Weeks was shown the police station -- in a building seized by the federal government when its owners turned a blind eye to drug traffic within -- and cameras hidden in the light poles. "It's a deterrent, mainly," said Lanzilotti. There were also empty stores, victims of an evolving street economy.

"Our goal is to get people not only working, but living downtown," said Weeks.

"Ours too," said Lanzilotti. "In the '60s to the '80, it was a crazy, uncontrolled building boom, with little thought to the overall architectural environment. We're trying to make it more harmonious."

But making the streets nicer attracts the homeless. "No one has yet figured out how to handle the homeless," said Lanzilotti.

"One-way tickets?" asked Weeks.

"They do that here," said Lanzilotti. "Except they're coming in, not going out."

Click for online

calendars and events.