Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Graphics By Kip Aoki, photos by Dennis Oda, Star-Bulletin

After decades of delays and

By Burl Burlingame

arguments, the Waikiki War Memorial

Natatorium is patched up to

revive some of its former glory

Star-BulletinWithin a few months of the Natatoriums's completion in 1927, rust was leaching through the concrete and staining the surface, paint was peeling, concrete was chipping, and the water -- well -- the water was full of bacteria and silt.

Memorials meant to last forever need maintenance. Honolulu kept putting off the expense of fixing the Natatorium, and the structure deteriorated to the point where it needed professional help.

Seventy-three years later, the restoration is underway, with work by U.S. Pacific Construction.

The work on the Natatorium has been "complicated, complex and interesting," said project manager Ed Deucher. "The guys enjoyed it. It's wasn't like working on a high rise, or pouring a 40-yard slab. No. They want people to say, 'Look at that!' They're proud to have been involved."

The effort used modern materials to make everything old look new again.

"Cracks -- there were a lot of cracks! -- were injected with a two-part epoxy and the excess was cleaned off," said project manager Ed Deucher. "The epoxy when it sets is stronger than the material around it! We'd sand it down until the crack was gone."

URNS

All eight urns were chipped and cracked. The damaged areas were

injected with epoxy and masoned by hand. After repairs were done,

a cement wash was added for overall enhancement.

Sculptural elements that had weathered away or disintegrated were built back up with a polymer cement, "put on like with a butter knife and sanded off smooth," said Deucher. "It's about the consistency of pancake batter. We also used it to plug those 'bug holes' in the surface of the cement."A couple of leaves around the memorial arch were restored with a thicker polymer cementlike product, and six coats of rubber were brushed over them to make a flexible mold. Another layer of hard plastic was laid over the rubber to keep the mold from flexing and distorting the castings. Additional leaves were then created with these molds.

EAGLES

The eagles were all severely damaged. The head was missing

on one of them and had to be recast and reattached. The mold

for the new head was created using one of the other eagles.

A similar mold was made of the eagle's head, cut "in two parts like a taco shell and held together with a tire inner tube," said Deucher. The cement used was a special mix that replicated detail perfectly and had enough body to keep from slopping out of the mold.One problem with the structure was the inclusion of tiny bits of steel rebar to add strength. "Air, salt, water -- the steel corrodes and expands," said Deucher. "A one percent expansion, and the concrete falls apart."

U.S. Pacific replaced any steel rebar they could find with a new product, a kind of fiberglass rebar that is impervious to the elements.

Some smaller nicks, such as those on the wreaths, were left as evidence of the monument's natural aging. "Fixes on them would have looked like chewing gum stuck on, anyway," said Deucher.

At some point in the past the Natatorium had been painted white. Deucher replicated the original color of the cast stone with a modern acrylic paint. "This stuff has a five-year guarantee instead of the usual one year," he said. "We'll see."

ORNAMENTAL FACADES

Garlands and ornate facades were repaired using fiberglass

reinforcement bars which do not rust.

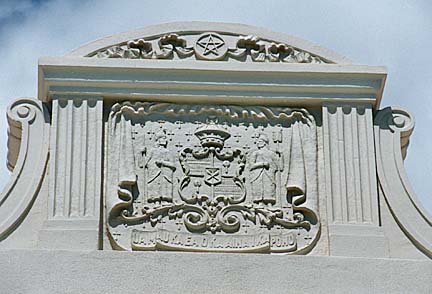

MEDALLIONS

The medallions are original. They required only cleaning with

a pressure washer. The medallions were used as a color

guide for painting the rest of the structure.

GLASS WINDOWS

Intact, original glass on the windows were mixed and matched for

symmetry. Missing or cracked glass panels were replaced with new,

custom-made glass. All window frames had to be replaced and

repainted due to wood rot and termite damage.

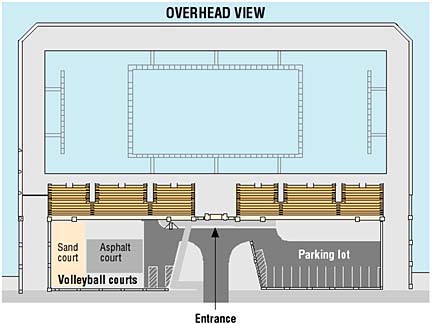

BLEACHERS

The bleachers were repaired using the same method as the walls

and columns. New railings and wheelchair stations were added

to meet Americans with Disabilities Act guidelines.

WALLS AND COLUMNS

Weak areas were located and knocked out. The holes were filled

with concrete to solidify structure. Rusted steel beams

were replaced with new ones.

FLAGPOLES

All flagpoles are originals, made of redwood.

Arch coincided

By Burl Burlingame

fashion of the day

Star-BulletinTHE people of Hawaii were proud of their participation in the First World War, and immediately after the conflict ended, the territorial government purchased the William Irwin Estate in Waikiki and created a public area known as Memorial Park.

The 1920s were a boom time in Hawaii and the rest of the country, and that sense of national bustle was reflected in the great number of public structures built. Most of the classic public architecture in Honolulu was created at this time.

It was also a period of intense interest in health and fitness, and organized sports and the Olympics dominated the American psyche. Hawaiian athletes ruled the sport of swimming worldwide.

So when the time came to memorialize Hawaii's unique contribution to world peace and the "War to End All Wars," these elements came together in the zeitgeist of the period.

A committee of well-known architects, including the famous Bernard Maybeck of California --whose Palace of Fine Arts near the Presidio in San Francisco is all that remain of his monumental Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915 -- decided, to everyone's delight, on a traditional "beaux arts" triumphal arch framing the entrance to a "living" memorial of a community-sized swimming pool.

This combination of old and new, of dedication and sacrifice, of gesture and utilitarianism, struck a chord.

The memorial's final design was drafted by Lewis Hobart, also of San Francisco (check out the California Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park) and incorporated a salt-water swimming pool, the largest in the nation.

A similar effort in the Bay Area, the 1925 Richmond Municipal Natatorium, nicknamed "The Plunge," used a combination of fresh and salt water. It is the largest and oldest indoor pool in the Bay Area, and like Honolulu's Natatorium, is in need of restoration. Funds are being raised for the effort.

In the roaring '20s, immersion in salt water was thought to be therapeutic, and public swimming, once an unusual sport, was established as a national craze. And so the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium is not only a monument to Hawaii's sacrifices in wartime, it is a capsule testament to the feelings and fads of the time in which it was created.

PHASE II RENOVATION:

The pool may be renovated later pending approvals. The city

administration wants to level off the pool's bottom, and add larger

circulation openings. Also, the pool's deck would be repaired.

Unveiled: the partial restoration

What: Rededication ceremony for the 73-year-old Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium, coupled with Memorial Day ceremonies

When: 10 a.m. Sunday

Parking: Shuttle service from Kapiolani Community College will begin at 8:30 a.m. The shuttle will run 30 to 45 minutes after the ceremony ends.

What was restored: The bleachers, public restrooms, shower/locker areas and facade, including four ornate eagles and eight urns. The fate of water-based parts of the project, including the pool, remains undecided.

Restoration cost: Work done so far cost $4.4 million. The original contract was for $11.2 million.

History: The natatorium opened in 1927 at a cost of $252,000. The architect was Louis P. Hobart, who received $10,000 in prize money as part of a design competition. Hobart also designed the Grace Cathedral and the aquarium at the Golden Gate Park, both in San Francisco. The natatorium was closed in 1979 due to health concerns.

Click for online

calendars and events.