Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Saddle up

... as we take you on a ride

Facts & glossary By Cynthia Oi

down big, bad, mostly

barren Saddle Road

Star-BulletinMIDWAY between Hilo and Waimea, along the Saddle Road where Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa enclose verdant kipuka and fields of lava and powdery dirt, Kimo Pihana and Keoni Choy chanted.

They stood behind an ahu they had erected on Jan. 1, aligning the rocky platform with the sun when it dawned on the new year. Nearby, two lauhala kahili they also had put up resisted the stiff, cold wind that swept away their voices.

Click here for Quicktime

Click here for RealVideo

Download RealPlayer 7

With the men bare chested and tattooed, with lei and ti-wrapped offerings on the ahu, the ice-blue sky and the spare landscape, the scene looked like one from ancient days.

But it wasn't, and Pihana, the elder, railed against the intrusion of Westerners on land he considers sacred to his nation and his people.

"Look this road here," he said, lifting his hand toward the two lanes of rough black top running past the dusty clearing where he and Choy parked their pickup truck.

"This is a spiritual gathering place -- between Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. Mauna Kea is the birthplace of Hawaiians.

"But this road run right through here. Why? No need."But if there was no road, getting to this site would be quite a hike for him, wouldn't it? Pihana smiles sheepishly, then laughs.

It is not called the Big Island for nothing.

Hawaii claims 4,028 of the state's 6,423 square miles of land, about the size of Connecticut. In comparison, Oahu's 590 square miles is puny.

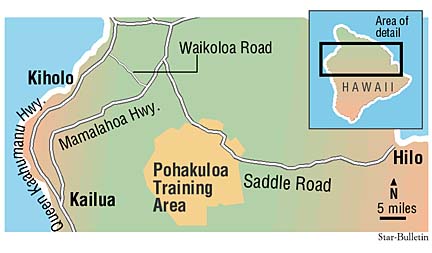

To get from one side of the island to the other, there are three choices: drive along the Hamakua Coast and the northern slope of Mauna Kea; south around the foot of Mauna Loa; or between the two volcanoes on a 48-mile stretch called the Saddle Road.Jamie Segawa, a lifelong Hilo resident, usually chooses the northern route, once in awhile the southern route, but almost never the Saddle.

"People drive too crazy on there," she said on a flight home from Honolulu. "Plus, it's hard on the car."

She sums up succinctly the problems with the Saddle Road, problems the military and the federal, state and county governments want fixed. But as it happens when there are many cooks in the kitchen and many elements to consider, the fixing won't be quick and easy.It has been 58 years since the Army carved the Saddle Road over foot paths and wagon trails. In a sense, the need to improve the road began then, in 1942, because the highway was constructed as temporary wartime access to the Pohakuloa Military Training Area.

Since 1987, when the Army began seriously considering improvement, the project has moved in fits and starts as government leaders, residents, hunters, environmentalists and business people debated the best way to go about it.

In the late 1980s, the county fixed about 14 miles at the Hilo end. In 1993, a community task force was formed to study the entire project. In 1997, it seemed that work would begin in a few months. That was delayed until fall 1998, which officials saw as optimistic because there was no funding yet for the state's portion.In 1999, with the final environmental impact statement in place, it looked like preliminary work on the military segment could being this fall. At a public hearing in April that was supposed to be the last step in the process, another monkey wrench hit the works: a hunter and former state legislator questioned a realignment that would go through a palila habitat, even though no birds now live there. The matter is pending.

The Federal Highway Administration says the whole project "could be completed as early as late 2008," but there are doubts.

"When it happens, it happens," said a middle-age fellow buying ahi shoyu poke at the KTA supermarket in Hilo.

Marnie Herkes, a task force member, said she hopes to see the project completed before she dies.

"Let's see -- I'm 68 years old now. It will probably take the next 20 years," she calculated. "Well, yeah, maybe I'll see it," she said, laughing.

The Saddle Road is one of the most dangerous in Hawaii.

Accident rates are more than 80 percent higher there than on other rural two-lane highways in Hawaii.

Although the huge protrusions of Mauna Kea (13,796 feet above sea level) and Mauna Loa (13,679 feet) leave enough land between them for the road, their mass forces the highway up steep grades. From Hilo to the central saddle, the road rises from sea level to 6,600 feet, then drops away to 2,500 feet on the west end.

Sharp curves through long series of hills and gullies create a roller coaster ride that can sicken those weak of stomach. Oncoming vehicles remain hidden until the last minute. Other drivers must be trusted to yield rights of way across dozens of one-lane bridges.There are few places where a driver can pull off safely. Narrow shoulders fall away from the cracked and potholed pavement. The road's edges are so rough that drivers speed down the middle, straddling the yellow line. Headlights are required day and night to give drivers a fair chance to see each other.

Speed limits vary from 10 to 45 mph, but tanker trucks, tourist compacts, utility vehicles, vans and pickups haul as fast as conditions allow; there are few places for speed traps.

Thick fog and clouds of dust often obscure vision. Fast-moving rainstorms slick the road surface and pond in the gullies.

But with all this danger comes a varied beauty that stuns the senses.

The Saddle Road begins just west of Kaumana, a small settlement in the hills above Hilo. It twists through a neighborhood of small, older homes that are slowly giving way to larger, more upscale structures.

Past Kaumana Caves, a small, neat building with a porch out front displays a sign: "Last Stop before Kona."

Susan Tomono and her brother, Dennis Kondo, have run the All Things Store for about five years. They put up the sign more for amusement than to attract tourists.

"Tourists don't normally stop," Kondo said. "It's more a local neighborhood kind of thing. Local people come here instead of driving all the way to Hilo."

The sign is truthful. Except for the Ellison Onizuka Astronomy Complex on Mauna Kea road, where you can get a cup of instant coffee ($1 donation) and a sip from a water fountain (free), there's no place to get sustenance until you reach the end.From Kaumana, the steep road passes through the Hilo Forest Reserve, thick with 'ohia and fern. In the days before the Merrie Monarch Festival, hula halau members gather the plant materials they need for their costumes.

Because this part of the road was repaired in the 1980s, the pavement is mostly intact and except for uneven surfaces and rolling hills, drives easily.

Between the trees, there are glimpses of Mauna Kea's summit, its white-domed observatories looking like gecko eggs.

When the forest dwindles to lava fields, the sense of the road's name becomes apparent.

On one side, the blue-gray points of Mauna Kea rise sharply. On the other, the round, feminine profile of Mauna Loa stretches languidly across the horizon.

At this high altitude, the sky is crystal blue, the air thin and chilled, hinting at occasional frost and snow. Except for the wind, the silence is complete.

After miles of gray, black and brown lava, spots of bright turquoise at the foot of the Mauna Kea access road seem like a mirage. They are, of all things, four portable toilets, lined up in the clearing at the bottom of Pu'u Huluhulu.

A shelter carries a sign that reads "Kipuka Pu'u Huluhulu Hunter Licensing Station." Another on a placard says "Pu'uhonua O Na La'au Maloli Native tree sanctuary and nature trail."It is here that elder Pihana and his mamo, Choy, have come to place more offerings on the ahu and to clean up the broken glass, soda cans, cigarette butts and general litter in the area. The hefty Choy tossed planks of charred wood into their pickup. They had made a fire to keep warm during a ceremony a few days earlier.

Pihana, who describes himself as a kahuna and elder, believes it is his responsibility to maintain the land surrounding the ahu.

Of particular concern is the increasing development of the Mauna Kea summit with the observatories he calls golf balls.

"Why do they need to put up more things to see the stars? Our people have walked the same paths. We are navigators. We know all the stars and all the directions," he said.

Across the clearing, a Mustang convertible, likely a rental, pulls onto the Saddle from Mauna Kea road, heading back toward Kona.

Renegade tourists often ignore rental car companies' ban on driving the Saddle Road; the lure of the observatories and the above-the-cloud views from Mauna Kea's summit prove too much for them to resist.

Pu'u Huluhulu butts up against the military training area. This is evident without maps because the condition of the road begins to deteriorate.

Cracks zigzag across the surface, potholes become more frequent and sharp, tire-ripping edges protrude from the pavement.

A few miles into the area, a shrine memorializes an accident victim. A cross, scattered liquor bottles, soda cans and a stuffed green frog decorate rocks arranged in a rectangle. A T-shirt emblazoned with "We love Froggy" flutters from a pole jammed in the lava.

As the road takes a northward swing, the numerous signs that order drivers to "Turn on Lights" followed by others that simply ask "Lights On?" become more meaningful.

Something about the drop in altitude and warm coastal air pushing against cold air from the two mauna triggers fog so thick that seeing beyond the hood of a car becomes impossible. Only the yellow line on the loopy road is visible through the area where one-lane bridges seem most abundant. Cars crawl along slowly, headlights bouncing of the haze.

Just as quickly as it formed, the fog dissolves, unveiling dry, high pasture lands spreading in contrast toward the deep-green Kohala Mountains and the sea.

Signs of civilization appear: driveways leading to pricey-looking homes, fences, bunkhouses and other ranch structures. Stands of trees welcome the eyes after miles of scrub and lava.

At the same time, the road surface deteriorates even further, jouncing suspensions and jarring teeth.

Suddenly, there's a stop sign. The Saddle ride is over.

Mamalahoa Highway swings by, a smooth, busy thoroughfare that in 30 miles south hits Kailua-Kona and 10 miles north, Waimea.

Herkes, the task force member who is also head of the Kona-Kohala Chamber of Commerce, wants to see the Saddle Road improvement completed -- for professional and personal reasons.

As a businesswoman, she believes the road will open the island's job market, especially on the east side where jobs are scarce.

She said that more than 25 percent of Kohala resort employees live in East Hawaii. A good road will entice more of those residents to jobs on the west side, perhaps cutting the island's unemployment rate of 6.7 percent.

Also, more than 60 percent of visitors make Kona their destination. If these tourists can travel easily to the Hilo and its attractions, she said, the weak economy there will get a boost.

Herkes lives on the Kona side and her job is based there, but she drives the Saddle Road at least once a week, sometimes as many as three times a week.

"Like today. I just drove over to Hilo. And I'll be driving back tonight," she said last week. And though she's used to the trip, "it would make my life easier" if the road was fixed.

The Saddle Road is called bad, but all it is is a busted-up old highway. Along its length unrolls a sampling of the Big Island's beautiful and diverse natural landscapes.

It is the shortest way to get between east and west. The risks of driving the road must be weighed with the reward of the visual and environmental experience.

The values of good and bad may more correctly apply to the speeding, inattentive, self-focused motorists.

No amount of improvement to the road can change its users.

Plans call for reconstruction of the Saddle Road in four phases, with tentative completion by late 2008. Saddle Road construction

Section II: The Pohakuloa segment between the Mauna Kea access road and mile post 42, where the road now veers to the north.

Section I: The improvement would take the road from its present course and route it more directly east-west to Mamalahoa Highway.

Section IV: From Kaumana above Hilo to mile post 9.

Section III: The segment from mile post 9 to the Mauna Kea road.

Construction costs: $165.2 million

Ahu -- Altar, shrine Glossary

Kahili -- Feather standard symbolic of royalty

Kipuka -- Clearing in a lava field where there may be vegetation

Mauna -- Mountain

Palila -- A gray, yellow and white Hawaiian honey creeper endemic to the Big Island; endangered

Click for online

calendars and events.