Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

The soldier's lifestyle places

even more stress on single parents

and their childrenNavy children miss mom

By Gregg K. Kakesako

when ship sets sail

Star-BulletinIT'S barely 4:30 a.m. The Helemano darkness is broken by the shrillness of Laura Drakeford's alarm clock.

The 29-year-old 25th Infantry Division soldier glances at her Bible.

"That's where my strength lies," says the single mother of two. "I'll just sit there a few minutes reading in the morning and studying my devotionals. I like it then because it's so quiet."

But within minutes, Drakeford will have to get 7-year-old Jonathan and 18-month-old Jaron on the road to their day-care providers.

Adhering to a schedule with almost military precision, Drakeford, a unit supply specialist with the 162nd Air Defense Artillery, knows she has a little more than 90 minutes to make the seven-mile trip from Helemano to Schofield Barracks. With two stops in between, she has to make it to J Quad to stand formation and roll call at 6:15 a.m. each weekday.

Today, there's a twist to the military adage, "If Uncle Sam wanted you to have a wife, he would have issued you one."

Many military members not only are women, but many, both men and women, have children. And a large number of them are single parents.

When Sgt. Maj. Jerry Taylor enlisted 20 years ago, fewer than 20 percent of soldiers were married and had children.

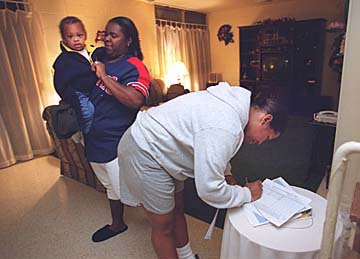

The hectic morning

of a soldier momPhotos by Ken Ige, Star-Bulletin

Laura Drakeford's day starts at 4:30 a.m. so she can get two

sons taken care of before her 6:15 a.m. Army roll call.

Photos, top to bottom:About 4:50 a.m.: Drakeford and her elder son, Jonathan,

9, brush their teeth as she towels his head.About 4:50 a.m.: Jonathan helps his mom with laundry,

taking his bedding for a wash to minimize dust mites.About 5:30 a.m.: After two loads of laundry and a

routine that includes giving both asthmatic sons medication

via inhalers, Drakeford gets ready to take the boys to their sitters.

The guys, meanwhile, catch a little sleep.About 5:30 a.m.: After dropping Jonathan off at the

Youth Center at Helemano, Drakeford leaves Jaron, 18 months,

in the arms of his care provider, Valerie Davis,

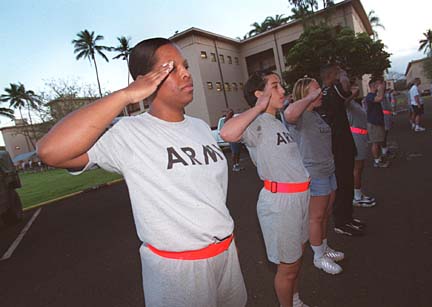

at Schofield Barracks.At 6:15 a.m.: With her sons taken care of for the day,

Drakeford reports for roll call; physical training begins at 6:30

a.m. She'll pick her kids up at 5 and 6 p.m."I would guess that, now, that figure is much higher," said Taylor, 39, who serves as a fire support operations sergeant major in the 25th Infantry Division's Headquarters, Headquarters Battery Division Artillery. "As things change, the Army has to change its rules and regulations to keep pace," said Taylor, who recently took over care of his 13-year-old son as a single parent.

"Command has to realize that we don't have a spouse at home who can help hold everything up," added Drakeford, whose two sons are asthmatic. "I am a single parent. I am an E-4 and nearly 85 percent of my pay goes to child care."

Sgt. Johnnie Hughes, another 25th Division soldier who was a single parent of two boys until she recently remarried, said that at times, "I was at home with a pot in one hand, a spoon in another and you have this baby screaming and pulling at your leg ... and this is after you spent a day getting hassled at work."

Staff Sgt. Machelle Jones, a supervisor with the 25th Supply Replacement Detachment, said she understands that as a soldier the mission must come first.

"But at times, I have to weigh what's right for my child and my job," said the single mother of an 18-month old son.

A 1993 study of Army families noted that there was very little research and policy attention paid to military families before the 1960s. The demographics of Army personnel in 1993 showed that 2.3 percent were single, custodial parents. The study also found that 57 percent of those parents were women.

That number has climbed. Of the 473,769 soldiers today, 4 percent of commissioned officers and 8.4 percent of enlisted soldiers are single parents. Fifty-six percent of male soldiers and 45 percent of female soldiers are married.

The combination of shortages of high-quality male recruits at the start of the all-volunteer force and the changing role of women in civilian society led to the increased numbers of women soldiers.

In 1972, fewer than 2 percent of Army soldiers were women; in 1992, the figure was 12 percent. Today, about 70,000 Army soldiers are women, making up 14.9 percent.

In addition to the normal stresses of raising a family, the risk of injury and death, frequent geographic relocations, separations, long duty hours and shift work, unpredictability of work hours and isolation from civilians add burdens.

There was a 10-month wait list when Spec. Christine Warren, a 25th Division legal specialist and a single mother, started looking for a child-care provider for her 8-month-old son.

Army officials said the time a parent has to wait varies.

Even before her second alarm sounds at 4:40 a.m., Drakeford has measured several scoops of coffee for her coffee-maker and hustled Jonathan into the shower. By 5 a.m. Jonathan has finished brushing his teeth and has stripped his bed of its sheets and blankets and taken them to the laundry room.

"There's always clothes in either the washer or the dryer," Drakeford notes, explaining that because both of her sons are asthmatic and have allergies, she has to take extra care in keeping her three-bedroom home free of dust, mold and mildew. The two boys are especially allergic to trees and dust.

"I have to mop every day to keep the dust down," said Drakeford, pointing to the bucket of laundry bleach and water solution she uses daily. She also can't have any carpets or drapes in her Helemano Military Reservation home.

At 5:20 a.m., Drakeford has her two sons in the kitchen where shelves of medication are stored. "I have to make sure they get their medicine every morning."

The need worldwide: 298,000 spaces; currently available, 172,000 spaces. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE PROJECTIONS

By services:

Army now meets about 60 percent of its need for 111,300 spaces.

The Air Force meets 56 percent of its need for 87,700 spaces.

The Navy meets 54 percent of its need for 74,200 spaces.

The Marine Corps meets 58 percent of its need for 24,300 spaces.

Gregg K. Kakesako, Star-Bulletin

By 5:30 a.m., she has to have both in her car on their way to her first stop, the Helemano Child Development Center, where Jonathan will get his breakfast before catching the bus to Helemano Elementary School.

"If I do it any later, I won't make it," she says.

Half an hour later, Drakeford drives up to the Schofield Barracks home of Valerie Davis, who has been taking care of Jaron for several months. He will be there until Drakeford picks him up shortly after 5 p.m. She'll pick Jonathan up an hour later.

It's a routine that Drakeford has to maintain daily, except for Thursdays, when her unit usually goes on a road march, complete with a full pack, helmet and weapon.

"When we went on an eight-mile march, I had to be up at 2:30 in the morning to get my sons to a friend who lives in the barracks," she said. "When we do a 12-mile one, I don't even know what time I get started."

By 6 every night, Drakeford is back home working with Jonathan on his homework. "Sometimes he does it at the day-care center, but I always want to check it to make sure it's done right."

By 8:30 p.m., she tries to get Jaron into bed. "It doesn't always work ... but I try. I also try to get Jonathan down by 9, but that doesn't always work either ... Then I try to find a little time for myself ... I take a bubble bath and then read. I read my Bible and sometimes I fall asleep reading and when I wake up the Bible is by my side."

"The bottom line," says veteran soldier Taylor, "is that the change has to come from the top to provide a better system for single parents.

"The Army has said we will allow single parents," added Taylor, who sometimes brings his son to his workplace after school, "then it has to have better solutions in place to take care of them."

Hughes and Drakeford have served under supervisors who have been less than sympathetic to their situations.

"I had a problem with an NCO (noncommissioned officer)," said Hughes, 29, "who always was mad that I stayed home with my sick child."

Child-development-center rules forbid parents to leave a sick child.

Jones, who has a daughter who suffers from asthma, said Army supervisors should be understanding that "when my child is sick I should be at home with my sick child. When I am sick, I am allowed to stay home sick."

The Army, like other services, has family support groups for dependents when military spouses are away.

"When you are without a spouse the family support group is of little help," Drakeford said.

So Jones, Hughes and Drakeford have had to turn to others.

They said they don't know where they would be without the help of their family-care providers. For Jones, it is Jada Pugh, who cares for five other children besides her own, and for Hughes, it is Javonna Slaughter.

Drakeford considers her family-care provider, Davis, a lifeline.

"She's a blessing," Drakeford said. "When I need someone to talk to when I am stressed -- even when I am at work -- I can call Miss Davis.

"I never have to worry about my baby."

The Military Child Care Act sets fees for child-care centers and sets up subsidies for family child care. Military options for child care

There are child-development centers at more than 300 military locations and more than 9,900 family child-care homes and school-age care programs. The Military Child Development Systems has three components:

Child Development Centers provide care for children 6 weeks to 12 years of age, Monday through Friday for 12 hours.

In-home family-care providers in government quarters for children four weeks to 12 years old.

School-age care programs for children ages 6 to 12 before and after school, during holidays and summer vacations.

All single parents must have a list of people they can turn to if they are going to be in the field or in training or even deployed for a short period of time. A more comprehensive plan as well as funding to move a child to a long-term care provider also must be on file.

In Hawaii, the Army maintains five child-development centers that serve a total of 560 children. Two are at Schofield Barracks, serving 300 children, and the rest at Helemano and Aliamanu military reservations and at Fort Shafter.

The Army also has 63 family-care providers who take infants into their homes. They fall under two categories:

Only three infants and toddlers under the age of 3 can be cared for by a family-care provider.

Six children can be cared for at a time, when older toddlers and children up to the age of 12 are involved.

Children miss mom

By Gregg K. Kakesako

when ship sets sail

Star-BulletinWHEN Navy Petty Officer Jeanne Terry went to sea for six months last June her 6-year-old daughter Tanai'ja went to Florida.

Petty Officer Danette Battle hasn't seen her 8-year-old daughter, Danielle, for 16 months.

Both are divorced and single sailor moms at Pearl Harbor and crew members on one of the Navy's newest guided missile destroyers -- the USS O'Kane -- which will leave on its first western Pacific deployment next year.

Battle, 34, will be reunited with her daughter -- who has been living with her father in Arizona while the Navy petty officer was getting settled with her new ship and duty station -- on May 26.

"But I speak to her almost every day," said Battle, who has been in the Navy for 16 years. "We write a lot of letters and keep in touch with pictures ... she thinks she's going to do a lot of surfing. She's very excited about coming here."

When the O'Kane left a Maine shipyard for Pearl Harbor on June 22, Terry sent her daughter to live with her great-grandmother in Florida. It wasn't until Christmas Eve when great-grandmother Mary Hoskins, Tanai'ja, and 3-year-old Jaylin arrived in the islands and the family was reunited.

A LOOK AT THE NAVY FAMILY

Men: 319,018

Women: 49,156

Single men with children: 18,057

Single women with children: 5,778

Married women: 17,708

Married men: 170,358

Source: U.S. Navy

"It was really hard leaving her," said Terry, who has been in the Navy for 14 years. "It was the first time we had been separated, and she didn't understand why I was leaving and kept wondering if it was something she had done.

"Three days before I had to leave I talked to her and explained what I was doing and that it had nothing to do with her behavior. Although she was still upset, after she understood that I would eventually be picking her up she felt okay."

In Terry's case, her preparation helped her daughter through the transition. Son Jaylin was too young to comprehend all that was going on, she added.

However, a study by Old Dominion University in Virginia shows that some children don't handle the separation well.

Michelle Kelley, an associate professor of psychology, compared 75 Navy moms who were deployed with those of 52 Navy moms who had shore duty between 1996 and 1998 in Norfolk, Va.

Her study revealed that the children of mothers who are deployed are more likely to experience feelings of sadness and anxiety before and during the deployment. But the study does not show that Navy children may be more prone to mental disorders than are children of civilians.

Today, there are 49,156 women in the Navy and 5,778 are single moms. The Navy reports that more than 18,000 men are single fathers.

With the military force increasingly relying on women, single parents and working couples, comprehensive child and family programs are necessary to maintain combat readiness and to continue to recruit and retain highly skilled military personnel, the study says.

All services here maintain family-support centers at Oahu military bases that provide single parenting and parenting classes geared toward stress in the home and the work place, anger management, sexual abuse, child and spousal abuse, deployments and financial management.

The study's author notes that when fathers are deployed their children weren't affected for as long a period as the children of deployed moms.

Navy service requires alternating ship and shore assignments throughout the course of a person's military career. Ship assignments involve deployments lasting up to six months and other absences range from days to weeks.

Kelly said the study shows Navy parents the importance of planning and preparing their children for the separations that occur with regularity in military life.

Kelly's study and others show that behavior of older children tends to improve as they realize their parents will return and as they learn strategies for coping with periodic parental separations.

Battle said while she was stationed in Philadelphia her job as a Navy recruiter gave her some flexibility.

"I was able to drop her (Danielle) off at school in the morning and pick her up after school. However, there were a lot of times she would be with me at work."She had to do homework alongside of me or she would fall asleep waiting for me to finish. I would feel very bad, but it did help having her with me."

Terry, an information systems technician on the O'Kane, said her daughter has always traveled with her until last June. From 1993-96 Terry was stationed here on shore duty and then sent to Guam for two years until 1998.

BOTH Battle and Terry agree being a single mom definitely has it challenges.

"The job doesn't stop at 1600 or 1700 hours," said Terry, 32, who joined the Navy right after high school to travel and "do something different."

"You wonder at times... In the evenings we would be going over her homework or working on her spelling, then when it was done, she would tell me -- 'I want you to spend more time with me' -- and I stop: 'Didn't I just spend time with you working on your homework?'"

"You could be dead tired," Battle added, "but you have to be there for them ... it continues around the clock."

But Battle said that her daughter -- even though she may be an ocean away in Phoenix -- keeps her going.

"When things get tough on board," Battle said, "it's nice to walk off the ship and call her. It puts a smile on my face until someone makes me angry."

When the O'Kane leaves Pearl Harbor on its first six-month deployment next spring, Battle will send her daughter to live with her sister in Florida or her father in Phoenix; while Jaylin and Tanai'ja will remain with their great-grandmother who now lives with them here.

"The Navy has helped me tremendously," said Terry, who wants to get a bachelor's degree before she retires in six years. "But it is my children who define me and keep me focused."