Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Saturday, April 22, 2000

We have the knowledge to avoid

By Mary Anne Raywid

future Columbines. But do we have

the courage to make the bold changes

that will turn our schools into safe,

vibrant learning communities?

and Libby Oshiyama

Special to the Star-Bulletin

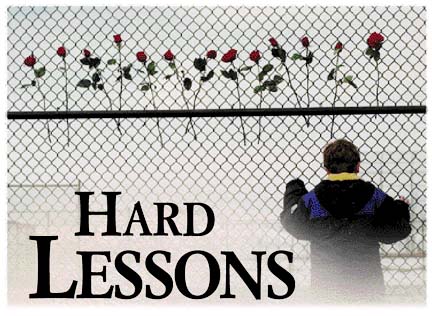

There have been multiple attempts to figure out the reasons for the Columbine High School tragedy. The availability of guns has been widely blamed, as has the violence depicted in films and videos. Some analysts have turned their sights on parental failure. Others have looked to deep-seated personality problems within the young assassins, while still others have focused on the seductive power of hate groups. There is probably some truth in most of these explanations, with the choice among them being largely a matter of individual perspective.

"The truth" lends itself to many interpretations. If we look to psychologists for explanations of human behavior, we characteristically get different answers from what sociologists would offer and different answers from what anthropologists would offer. Educators venture answers, too. But unless they are going to content themselves with mere hand wringing, they must look to explanations that schools can do something about. Otherwise they are simply placing the problem beyond their control.Actually, there is a good bit of knowledge suggesting directions that schools can take in order to avoid more tragedies like Columbine. It is also knowledge about which we can be fairly confident. The broad strategies that strike us as most promising pertain to school size and organization, as well as to what we teach -- both deliberately and inadvertently.

There is overwhelming evidence that violence is much less likely to occur in small schools than in large ones. In fact, not surprisingly, students behave better generally in schools where they are known. It is in large schools, where alienation often goes hand in hand with anonymity, that the danger comes. As James Garbarino of Cornell University, one of the nation's top scholars on juvenile delinquency, has put it, "If I could do one single thing (to stop the scourge of violence among juveniles), it would be to ensure that teen-agers are not in high schools bigger than 400 to 500 students."

As suggested by all the standard indicators -- truancy, dropout rates, involvement rates, graffiti, vandalism, violence -- youngsters in small schools rarely display the anger at the institution and the people in it that was so blatant at Columbine and is evident in many high schools elsewhere as well.

The evidence regarding school size and risk comes not only from individual school studies but also from research syntheses -- analyses of relevant studies undertaken across the country. Here are claims from three such syntheses:

Behavior problems are so much greater in larger schools that any possible virtue of larger size is canceled out by the difficulties of maintaining an orderly learning environment.Larger school size is related to higher levels of disorder and violence, student alienation and teacher dissatisfaction.

Student social behavior -- as measured by truancy, discipline problems, violence, theft, substance abuse and gang participation -- is more positive in small schools.

Research has consistently found that students at small schools are less alienated than students in large schools -- and this positive effect is especially strong for students labeled "at risk."

The reason size is important is because the first lesson Columbine seems to urge for schools is the need to make them genuinely user-friendly places for all students -- places where everyone is welcomed into a genuine community and each student is known well by at least one adult staff member who assumes responsibility for his or her positive growth and success.

The student assassins of Columbine, by contrast, were outcasts who banded together after repeated acts of rejection and humiliation by two high-status campus groups, the "jocks" and the "preps." And although they and others paraded around the campus in identifiable dress (black trench coats), gave one another Nazi salutes and submitted assignments that should have spelled danger (videos on killing, poetry about death, violence-filled essays), no single faculty member was in a position to put the picture together, and evidently none felt a personal responsibility to address these particular aberrations.

Indeed, with no one responsible for seeing and acting on the whole picture with regard to these boys, the multiple signs of trouble couldn't even be tallied. And the principal could report that he had actually never heard of the "trench coat mafia" in his school.

This situation is not atypical of comprehensive high schools of nearly 2,000 youngsters. In such schools, many students remain virtually anonymous for their entire stay. Others are singled out by their peers for harassment and humiliation, which teachers typically find beyond their province -- if they become aware of it at all. It is a mistake to assume that teachers in such schools don't care or that they are indifferent to students. We are reaping the results of the way we have organized schools and divided up staff responsibilities. We have apportioned things so that teachers' primary responsibility is not for youngsters but for content and grade levels.

Small schools have many advantages over large ones. Small schools, safer schools

They have greater impact, hence influence, on their students.

They have fewer and less serious behavior problems.

They narrow the success gap that separates the most and least fortunate.

They can more successfully stimulate student involvement and participation.

They elicit greater effort from students.

They have lower dropout rates.

Their students learn more and proceed more steadily toward graduation.

Education can be personalized only in small schools.

Only small schools can function as caring communities.

They are more cost-effective, costing less per graduate than other schools.

In small schools, almost all students fare better -- especially disadvantaged students.

Existing buildings can provide small-school benefits.

Existing buildings can be divided into schools-within-schools.

Separate, autonomous programs can be established, each with its own staff, students, distinctive theme and program.

(Guidance counselors too must focus primarily on accomplishing specific duties, like programming and college admissions, and with such large numbers of students that it is ludicrous to think they have time to find out what's going on in an individual youngster's mind.)

No matter what we focus on in articulating school organization -- content or something else -- it means that other things become less visible and may be obscured. Sometimes they are things that are centrally related to the kinds of human beings we are creating.

Making students the focus

Yet there are schools today in which students are the focus and these human requirements are being met. Such schools are largely to be found in cities -- which have been far more alert to potential crises than have suburbs and rural areas. But obviously one of the clearest lessons of middle-class, suburban Columbine High School is that violence is not confined to the inner city or to disadvantaged youngsters.The first requirement for making schools into communities where all youngsters are known is the one with which we began, the obvious need to make them smaller. You simply can't have much by way of genuine community in a school of several thousand. There are just too many logistical obstacles for community to emerge in schools of such scale. And so subcommunities of various sorts develop there instead -- cliques, including the jocks and the nerds.

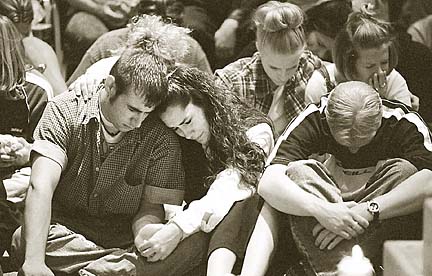

In most high schools, the cliques, plus the gangs formed outside school, are left to fulfill the human need -- peaking at adolescence -- for close ties and peer recognition. Our failure to acknowledge and respond to this need in school organizational design is strange: we know the "herding" instinct is strongest during adolescence. Never before or afterward does it seem more important to people. Yet most schools just leave fulfillment of that instinct to chance. Columbine suggests that if we fail to acknowledge and deliberately nurture human connection in schools, youngsters will find it for themselves. And it will not always be the kind of connection and connecting that we would want for the young.

There is another strange feature about the way we have organized high schools. We are quite aware that adolescents are not adults -- and that adolescence can be the most difficult and painful stage of growing up. Yet we defer little if at all to the immaturity of the school's "clients," placing them in the most unpleasant and demanding circumstances they may ever have to encounter: They are moved every 45 minutes all day long and are expected to shift attention and mental gears at the ringing of a bell. They can find themselves in seven or eight entirely different groupings during the day, with seven or eight different bosses (teachers -- who may not know one another, either).

And rules regarding their dress, speech and comportment may be rigid in an effort to exert control over the nameless faces. As the principal of one famous high school has put it, "If God knew what high schools were going to be like, he'd have made kids differently."

What do high schools need to be instead? Small enough so that people can know one another. Small enough so that individuals are missed when they are absent. Small enough so that the participation of all students is needed. Small enough to permit considerable overlap in the rosters from one class to another. Small enough so that the full faculty can sit around a table together and discuss serious questions.

Small enough to permit the flexibility essential to institutional responsiveness -- to the special needs of individuals and to the diverse ways teachers want to teach. (In large schools, instruction must always bow to the schedule, which controls everyone's time impartially. Small schools can simply suspend customary arrangements for a day or rewrite the weekly schedule as the need arises.)

As we analyze and reanalyze the tragedy at Columbine High School, many people identify it as a series of events crying out for education in tolerance. They seem both right and wrong.

Certainly they are correct in the notion that youngsters must be taught how to relate to others -- to groups as well as to individuals. The famous line from a song in "South Pacific," "You have to be taught to hate and fear," may be half right. But you also have to be taught to appreciate.

Thus positive lessons on how to see and treat others must be included in formal education. But to the extent that aims determine our strategy for reaching them, it might be well to examine whether "tolerance" is really sufficient. Tolerance, after all, is the parallel in human affairs of the laws we have established to bring "justice" to the public sector. They are parallel in that both are intended to apply not primarily to friends but to strangers.

Toward individuals for whom we lack the personal feelings we have for friends, tolerance is supposed to be the broad general attitude. And it is an attitude of neutrality or benign indifference: You live your way, and I'll live mine. We are really just beginning to sense that it is not enough.

There is much to recommend it as legal policy, but there seems less to be said for it as a general principle of living to be taught the young. There are other approaches that would probably have a lot more psychological validity. In the first place, it would help if schools modeled respect for individuals -- that is, if all coming in contact with the school -- students, parents, visitors -- were consistently treated with courtesy and in such a fashion that their dignity remained intact. This is a broader demand than we often construe it. It shows a lack of respect, for instance, says Paul Schwarz, former resident principal at the U.S. Department of Education, for school officials to fail to learn the names of students enrolled in a given school.

It shows a lack of respect for schools to repeatedly assign youngsters to groups widely recognized to consist of "dummies" or "losers." It telegraphs another sort of lack of respect when lavatory doors can't be closed or locked -- or when there is no toilet paper.

Somewhat more directly, youngsters must be taught about and held responsible for respecting their classmates. This is a matter first just of physical respect. Although we may think of this point as too obvious to deserve mention, a survey of one college class revealed that every single student in the class had been physically threatened by others in high school! But what is also necessary is respect for the individual's persona. It would be surprising if the ridiculing and the repeated rejections of the Columbine boys who became assassins were unrelated to their rage. But the kind of respect indicated will probably have to go well beyond the tolerance that schools typically state as their official position.

Teaching Empathy 101

We need to deliberately cultivate in schools the qualities associated with acceptance, such as empathy and compassion. This is not to say that we want youngsters to find acceptable any behavior that a schoolmate exhibits. But it is reasonable to ask them to accept that even behaviors we might abhor are motivated by the same needs that motivate our own behavior -- and that the needs, if not the manner in which we fulfill them, define the commonality among human beings.Again, these traits must be both modeled by staff members and deliberately cultivated among students. The major ways of cultivating them are, first, through the personal relationships that constitute school communities, but also through what is taught -- certainly in the humanities. Literature can instruct eloquently in kinship, empathy and compassion, as can people's history, to cite just two examples. Over the years, schools have tended to focus on making youngsters more informed, more rigorously trained, more skilled. Perhaps we had better begin focusing on also making them more humane.

As is the case with respect, there are other ways than the curriculum in which schools teach tolerance or acceptance -- or their opposites. Just as it is possible for institutions to operate in ways that make them, in effect, racist or ethnically biased, sexist or homophobic, they can also operate in ways that make plain their rejection of such stances. Some small schools guard against negative institutional bias -- and against the stinging comments youngsters can deliver to their peers -- by deliberately generating bonds among students.

Other schools content themselves with having strictly enforced rules against malicious statements. (At one small high school, for instance, one of the very few rules to which there can be no exceptions is "No dissing" -- no slurs, no taunts, no jabs.) And at another institution, the discovery of humiliating graffiti on a wall of the school prompted a three-stage response: first, indignation; then a student-led march through the campus; and then the establishment of "Acceptance Month.'"

High schools also must figure out ways to meet other adolescent needs. Young people need contact and interaction with adults -- and we seem to have forgotten how central such contact is to the purposes of education. A goodly part of what we are trying to do in educating, after all, is to sell youngsters the adult world -- to initiate them into its perspectives and cultivate appreciation for what it values. But we've been trying to do so on an absolute minimum of personal contact.

And as sociologist James Coleman pointed out, while so-called disadvantaged youngsters may be deprived of this "social capital" because their parents lack it, middle-class and affluent youngsters are often just as deprived of it because their parents don't spend the time to share it with them.

In high schools we try to dole out this precious capital in packages called "courses." And we do so in ways that reduce interaction demands on adults: One teacher is expected to lay it out for 30 students at a time, with minimal or no out-of-class interaction with most of them. But youngsters need to talk to adults, and education might work more effectively for many more of them if we built more interaction into the equation. You simply can't manage it when a teacher is responsible for 150 students.

This hardly suffices for knowledge transmission, let alone individualized instruction. Small schools manage to build interaction in a number of ways -- in assessment procedures wherein a group of adults confer with a student over his or her work; in mentorship programs that strive to generate long-term, significant connections between one adult and one youngster; and in joint-inquiry projects that cast students and teachers as co-researchers.

Even socially adept adolescents are often lonely. They need adults who will talk and listen to them. Moreover, they need to feel that they are being taken seriously by an adult. Today's circumstances honor well adolescents' desire to establish distance between themselves and those adults to whom they've always been closest. It fails the paradoxical need, however, to interact with other adults, to test ideas on them, to see what earns the approval of a respected adult confidante and what doesn't fly.

So how can we accommodate all of these needs and imperatives? What must we do to shift the sights of comprehensive high schools so that concerns such as these -- the teaching of acceptance and respect, the provision of cross-generational interaction -- can become prominent in their organization and programs? Some changes will certainly be required.

First, high schools would not exceed 700 or 800 if we were serious. It wouldn't have to mean new buildings. But it would require reorganization to break down an existing high school of 3,000 into perhaps five or six separate, autonomous schools, each with its own faculty and students and its own separate program. It's not impossible, and in fact it is being done in a number of cities. But it takes some venturesome and courageous leadership to redefine school organization this way.

But small is not enough. It is possible to cut high schools down to enrollments of 400 or 500 and then still operate mini-comprehensive high schools! To avoid this, schools must be reorganized to display alternative priorities and virtues. If the school's goal is to make the positive development of each youngster paramount, quite a reshuffling of roles and responsibilities will be necessary.

Schools of interest

The second requirement for making schools into communities is to find some equitable way to assemble students (and teachers) into groups in which genuine community can be launched and sustained. Routine assignment practices won't work because they don't produce groupings in which people have enough in common to generate community. We've tried age grouping in schools and ability grouping. Neither of these has yielded enough commonality for community, and ability grouping has proved highly inequitable as well. So why not try interests as the basis for grouping?Why not let teachers who share an interest -- in the arts, or in the sea, or in sports, or in critical thinking -- band together to offer a program that will attract students with similar interests? It doesn't mean that the school will teach only the content connected with the arts or the sea or with sports or thinking. Every youngster needs and should have a full curriculum. But it does mean that the sea or sports will provide the context in which as much of the rest of the curriculum as possible is presented.

This way, what calls the group into being -- for teachers as well as students -- is a shared interest or concern. This interest becomes the nucleus around which a school community can be based. It's not enough to ground a community, but it's a start -- as well as an acknowledgment of the obvious truth that a real community is unlikely to emerge from just any collection of human beings that chance brings together. For instance, teachers who disagree fundamentally on what education is about and what its top priorities should be cannot arrive at a very viable professional community. Youngsters who share few common interests or concerns aren't very likely to bond into a community of learners. To fail to acknowledge this (as we school people often do) is to close one's eyes to the way the world is.

The third requirement for making schools into communities is the recognition that it takes deliberate effort. It won't just happen by itself, even in a small school. Effective small schools accomplish this goal by organizing carefully hewn cooperative learning activities, community-building activities involving self-disclosure, and -- especially for severely alienated students -- collective problem-solving events.

Students as humans in full

A concern to establish community also requires seeing students quite differently. Teachers cannot be content with dealing with their students as one-dimensional, exclusively academic creatures. They must be concerned with them as multi-faceted human beings. They must commit to aiding development of multiple sorts -- cognitive, social, emotional, moral, as well as academic -- and this requires closeup knowledge of individuals. There are a number of approaches that can be used to stimulate the sharing among students that community must involve. For instance, students might remain with a single group for most of their classes and perhaps for several years.Arrangements are needed to generate close ties with at least one adult and one group of peers. In many schools, the practice chosen consists of advisory groups of perhaps 12 to 15 youngsters who may meet daily with the same adviser over a period of several years. There may also be out-of-school, weekend advisory activities, such as visits to college campuses. The adviser is charged with becoming a source of assistance and advice, an advocate, an adult friend and a liaison between home and school.

Successful small schools conceive of and pursue community in a variety of ways. One principal summarizes his school's philosophy as, "There are no strangers here." Another educator casts the ideal climate in terms of the "four Rs": mutual "respect" among all the school's constituents, "reciprocity" among students and between them and adults, "responsibility" to self and the greater community, and a "reverence" for place and its connections.

And as still others see it, establishing school community is a matter of deliberately fostering interdependence and interconnectedness among and between faculty members and students. Despite the different ways of expressing it, what lies at the core of all is a "personalization" that large schools, and even some small ones, lack an awareness of, and willingness to acknowledge and work with, human beings in full dimension, not just as students perceived in cohorts or batches to be processed (e.g. sophomores, the second-period German 2 class, gifted and talented, hyperactive).

Shifting to this perspective is not easy. But unless and until we do, we may well be headed for more tragedy and heartbreak. Until we make schools engaging learning communities whose members value those communities and feel welcome within them, we are right to think that the next Columbine could happen anywhere.

Mary Ann Raywid is professor emerita, Hofstra University,

Hempstead, N.Y., and a member of the graduate affiliate faculty, University

of Hawaii, Manoa. Libby Oshiyama is an international education consultant

whose home is in Hawaii. This commentary is reprinted courtesy of the

February 2000 Phi Beta Kappan, a publication of Phi Beta

Kappa International.