Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Waimanalo

farm family’s petition

designed to wash

out state’s flood ‘fix’

It hopes to head off a plan

By Lori Tighe

to demolish an old reservoir

that keeps flood water at bay

and Treena Shapiro

Star-BulletinThe vibrating ground woke them. "Oh no," David Kalama said.

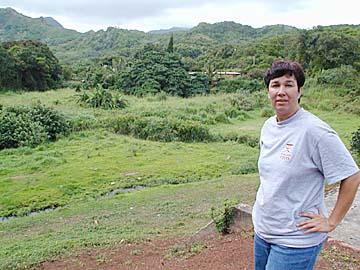

He and his wife, Kimberly, rushed out of their Waimanalo home to find water pouring down the mountain and their several acres of land flooded up to their knees.

"It was white, rumbling water, with floating telephone poles hitting us in the dark," Kimberly Kalama said. "My major concern was for my kids."

This is what happens to the Kalamas' yard when the big rains come. But the Kalamas say the state's plan to fix the problem is even worse.

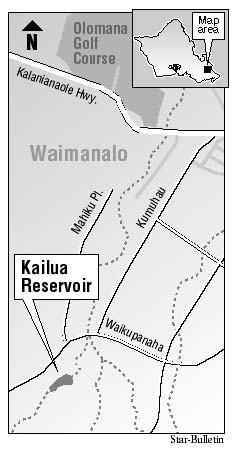

The state Department of Agriculture proposes to turn a century-old, abandoned Hawaiian reservoir in the Kalamas' back yard, once used to grow taro, into a stream.

The Kalamas fear it will take away a chunk of their land, threaten them and other downstream neighbors with catastrophic flooding, and pollute Waimanalo Beach.

The Kalamas now have a petition headed to the governor, with hundreds of names protesting the project.The state Historic Preservation Division plans to call for a survey of the reservoir and its adjacent dam to study their cultural significance.

"The dam itself is historic and evocative of the sugar plantation era," Sara Collins, Oahu archaeologist on the state's Historic Preservation Division, said yesterday. She had looked at the earthen dam last week.

"It's quite a complex system of tunnels and ditches and dams to move water into the fields. They were quite the engineering feat," Collins said. "I would definitely like to see a survey done."

In 1980, the Waimanalo ditch system was deemed eligible for the National Register of Historical Places, but the Agriculture Department, which owns the land, objected. In 1994, a local archaeologist petitioned to have the system included on the State Register of Historical Places, but again the department opposed it.

"There's not much left of the system. It's a big hole in the ground covered with brush," said James Nakatani, chairman of the state Board of Agriculture. "Safety is our biggest concern now."

The reservoir in its current deteriorated state poses a flooding threat to the Kalamas and dozens of other residents, he said. A major storm could fill it and burst through the dam, flooding the area.

The Kalamas say heavy rains bring silt, sediment and junk, including buckets of glass, abandoned refrigerators, animal carcasses, telephone poles and, once, a cage full of dead chickens.

All that could go into the ocean if the Agriculture Department breaches the dam, or breaks it and allows the mountain runoff to flow into the nearby stream and ultimately into Waimanalo Bay.

"This is the state's longest white sandy beach. It would turn into a muddy and polluted beach. Where else is it going to go?" said Joe Ryan Jr., member of the Waimanalo Neighborhood Board.

Even the department's project contractor, R.M. Towill, said it was concerned that a breach of the dam and loss of the reservoir may result in more frequent flooding downstream.

Waimanalo residents want an environmental impact statement done for the whole watershed area, and more alternatives, including restoring the dam.

But the Department of Agriculture said dam restoration, which would cost an estimated $3.4 million, isn't a likely alternative. Breaching the dam, the favored plan, costs $800,000.

"This reservoir poses a liability," Nakatani said. "I'm concerned we do something about it. But I agree we should look at how this affects downstream residents." He added, "Communication could have been a lot better," referring to the department's dealing with the community.

The Kalamas say the department never contacted them to tell them one-third of an acre of their land may be condemned for the dam breach. They learned that from the contractor, R.M. Towill.