Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Astronomers

wait for sun to

ring their bell

Every 11 years, the sun bursts

By Helen Altonn

forth with powerful sunspots that

disrupt high-tech communications

Star-BulletinUniversity of Hawaii solar scientists are waiting for a bell-ringer on the sun.

They're watching for a big burst of action there to herald the sun's 11-year peak of activity -- the solar maximum.

"Usually, there is one that rings the bell," said solar astronomer Barry LaBonte, with the Hawaii Institute for Astronomy.

"We're seeing more sunspots and bigger sunspots ... But we're kind of waiting for that one big complicated action to blow off a succession of flares," he said. "Usually, one starts the solar maximum."

The cycle is under way and the maximum should arrive within the year, possibly in early 2001, LaBonte said.

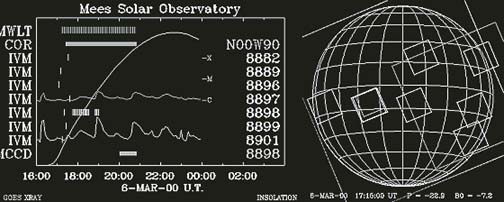

He and other Institute for Astronomy solar scientists are studying the periodic event with data from the Mees Solar Observatory on Haleakala, Maui, and the orbiting Solar and Heliospheric Observatory -- SOHO.

Recent images show a couple of big sunspot regions and a total of about a dozen at any time, LaBonte said.

Sunspot activity over the past 50 years has gradually increased, he said. "The most recent sunspot cycles were the biggest in recorded history."The present cycle is expected to be comparable to the others, "but not outstanding," LaBonte said.

However, predictions of solar maximum activity "are very, very sketchy -- more like earthquake predictions than weather predictions. We don't really understand all the mechanisms."

The difference now, LaBonte said, is that life on Earth is linked with high technology. Solar flares -- the largest explosions in the solar system -- can disrupt or knock out electronic and satellite communications, affecting radio signals, portable phones and pagers.

The energy equivalent of millions of 100-megaton hydrogen bombs exploding at once can be released by a typical solar flare.

"So when activity of the sun begins to disturb the environment around Earth, there are all kinds of unexpected consequences," LaBonte said. "Even people who study the sun get surprised at what happens."

To try to minimize the surprises, the National Science Foundation and Air Force Office of Scientific Research have launched a major scientific research program called "Space Weather," he said.

LaBonte and other astronomers are trying to find a way to peer inside the sun to see sunspots before they get to the surface. "It's turning out to be really hard," he said.

In at least some cases, they can see sunspots hours to a day or two beforehand. "It's just a hint -- like looking through a wall and seeing someone stand on the front lawn ... We need powerful X-ray vision."

The astronomers are using sound waves, which go through material, to probe the sun's interior. The SOHO satellite has a machine to measure the sun's oscillations to see what's inside.

The satellite is an observatory that sits outside the sun with about a dozen instruments to observe high temperatures, particles and mass ejections. Scientists so far haven't seen many high energy flares, which "change the whole character of the space environment," LaBonte said.

"What we are seeing because of the SOHO satellite are coronal mass ejections -- blobs of material that get shot from the sun pretty much the way you'd throw something out of a slingshot."

The sun has big magnetic fields that can get loaded with material, then "snap and fling that material out into space," he said. "If it comes toward Earth, it can excite the magnetic field, produce auroras and disrupt communications."

SOHO images picked up coronal mass ejections from a sunspot that went around the backside of the sun three days earlier, LaBonte said.

"It's a funny picture, like watching a train go around a mountain and you can see smoke coming off the horizon from the smokestack."

There were a lot of big sunspots last fall, then it faded, LaBonte said. "A month ago, the sun went back to being as quiet as it was in 1997 ... It went two years backward."

Then an outburst of activity occurred in the last week, he said. "It's as active as it has been for the last eight years. That's how quickly it can change."

The sun's 11-year cycle was discovered about 150 years ago, he said. It can be traced back to the first observations with telescopes by Galileo, he said.

The growing UH solar group has about $1 million a year for research and funding proposals pending. LaBonte said he has about $1.5 million through year 2002 for studies of solar activity related to the maximum and collaboration with spacecraft observatories.

"A lot of stuff is going on," he said. "It's very exciting. We're getting observations we never thought we could get."