Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Drawing power

Everett Y.S. Ching uses

By Nadine Kam

his artistic talent to stay

connected to a Hawaii

that is slowly fading

Features EditorEVERETT Ching was 9 years old when statehood came, but he still remembers being confused by his mother's sadness about the occasion.

"Everyone else was so happy, but she said Hawaii will never be the same."

One of the changes affected him almost immediately. As he recalls, the sudden availability of federal highway funds made it possible for the H-1 freeway to be built, swallowing up homes in the Punchbowl area where he grew up.

"The next thing I knew, the tractors and cranes came and my childhood friends were gone. They all were forced to move and went off to different schools. My mom said it was only by the grace of God that the pencil didn't take our house, too."

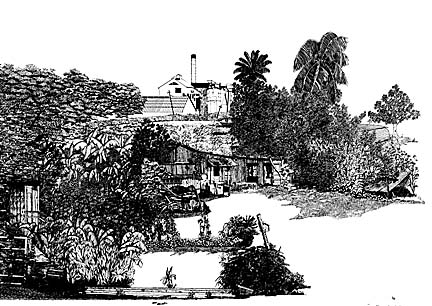

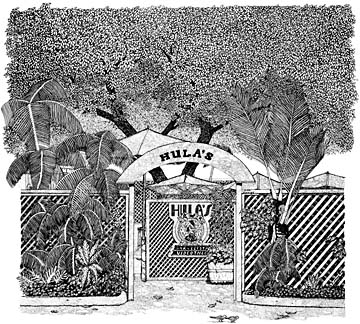

Now, with the touch of a pen, Ching now does the best he can to preserve some of his favorite places before they disappear. "The Disappearing Hawai'i," Ching's show of pen-and-ink drawings and collage, will be on view at the Pauahi Tower Gallery through March 25.Ching only began documenting churches, sugar mills and plantation homes in 1995 with encouragement from his wife Wendy Schofield-Ching and other artists.

"It was a self-esteem thing. Like many artists, I can't appreciate my own work. I just like doing it.

"You're very vulnerable when you put your stuff on a wall. But my friends said the public needs to see your work, and I do think it's important for future generations to remember these places.

"I have no control over anything, so the best I can do is put my ideas on paper."

Looking at the realistic detail of his renderings, it doesn't seem possible that Ching, a legal assistant by day, had no formal art training.

He spent two years in Vietnam before enrolling at the University of Hawaii with the goal of becoming an architect. Unable to meet the physics requirements, he switched to studying political science and majoring in journalism.

His journalistic skills come in handy in writing of his recollections and feelings about a place -- each about four to five paragraphs -- that accompany each of his drawings.

"At a lot of art shows, I find myself wondering what the artist was trying to get. The stories are a way of getting into my head as to why I did the piece. Each one says something to me."

Although he admits that peripheral buildings and a shrub or two sometimes get transplanted for composition's sake, for the most part, his drawings are true to the sites.

"Before working on a place, I need to have a rapport with it, and I feel that pretty quick."

In spite of his desire to preserve the ambience of earlier times, Ching makes it clear that he harbors no anti-statehood sentiments. "This is not a knock against progress, but I'd like us to be selective about what is lost.

"It's nobody's fault if a landowner decides he can make more money by tearing down an old building and putting up a strip mall.

"It's wonderful if we can save something, but it conflicts with the value of capital gains."

"I think America is a young, fast-moving society. I call this the McDonald's society compared to other countries in Asia and Europe. They really have soul because they're thousands of years old and realize the inherent wisdom of keeping old things instead of knocking them down.

"I noticed in Japan a skyscraper next to a 400-year-old temple. I think that's great."

To this day, Ching doesn't know why he started drawing, first picking up an engineering pen in 1989.

"I don't know how the pen got into my hand, but somehow it did, and I was sitting behind my house sketching the back of the house with a tree, and I loved the black ink on the white paper. It's almost like yin and yang. So pure and fulfilling to see something appear on paper, dot by dot, line by line.

"It's really good meditation when you're going on your 4,000th dot, or your 48,000th leaf."

Not that he counts.

"I'd go insane."

At one point in the learning process, he had left his work on a table while talking on the phone. The next thing he knew, his daughter Cady, who turns 10 this month, but at the time 3, announced, "I'll help you daddy," and took a purple crayon to the piece.

"I said 'I gotta go,' and ran to the drawing. But she was so happy all I could say was, 'I love the color. Why don't you finish it.'

"That's why I always say she is my teacher in art and life.

"I bring my daughter to the plantations and we introduce ourselves and people let us enter their homes.

"In spite of the hardships associated with the plantations, a lot of aloha spirit came out of those places because of the many ethnic groups that shared those communities. I met one Japanese woman who speaks fluent Hawaiian, and she said, 'I make a mean laulau too.' "

"Unfortunately, the sugar plantations are closing quicker than I can draw them."

On view

What: "The Disappearing Hawai'i: Works by Everett Y.S. Ching"

When: Through March 25

Where Pauahi Tower Gallery, Bishop Square,1001 Bishop St.

Admission: Free

Call: 734-8018

Click for online

calendars and events.