Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Chocolate pyramid cakes reach

for the heavens in this

baker's imaginationHow to bake a pyramid cake, and

By Cynthia Oi

how to cut it once it's done

Star-BulletinP YRAMIDS have snared Praseuth Luangkhot's imagination.

If he were a mathematician, perhaps the pyramid's relative numbers would likely be the reason; if an architect, construction principles would be intriguing. But Luangkhot is a pastry chef -- so what's the attraction?

A pyramid, he says, is like a human. It is anchored to Earth while its pinnacle surges toward the heavens, much like the human spirit. Its visual simplicity hides its complex structure.

Luangkhot likes them so much that he has made the form the signature dessert at his shop, JJ French Pastry on Waialae Avenue. Instead of stone and mortar, he builds his pyramids of powdered chocolate, cake and mousse.

Luangkhot, apron over his trim 33-year-old frame, is taking a rare break in a 14-hour day at his airy bakery.

His mornings are jammed with filling orders for restaurants that contract him to make their desserts: Chai's Island Bistro, Singha Thai and the Espresso Bar at Neiman Marcus.

Luangkhot's journey to Kaimuki began in Laos, where he was born to a Chinese father and a Laotian mother. He attended school until sixth grade, but after that, the Communist government closed the schools. He later learned a little English, but his accent is still French, the language he spoke as a small child.

After his father died, Luangkhot, his mother and two sisters came to the United States, settling in New York City. He attended classes in English, but money was tight. He felt he had to work to take care of his family.

With few skills, he went to a Roy Rogers restaurant to look for a job.

"The manager asked me if I speak English. I say yes, even though my English is not really good, because if I say no, I don't get a job. So I say yes."

Luangkhot appears slightly ashamed that he had to fudge the truth, his eyes blinking rapidly behind his glasses. The white lie caught up with him quickly. He was told to wear black pants and a white T-shirt to work; the company would supply him with a polo shirt with the Roy Rogers insignia to wear over the T-shirt. Luangkhot thought he was to buy a polo shirt, to be exchanged with one with the logo.

"I spent $12 on the shirt, and I thought that was a lot of money. But I bring it to the restaurant. The manager, he look at me. I think he know then I don't speak English, but he let me work."

The manager told him to sweep and mop the floors.

"I don't know what he is telling me, so I ask another person and he show me." Luangkhot mimics sweeping and mopping. "I understand then. With 'sweep' and 'mop' I start to learn English."

He was glad to have the job, but needed to make more than the minimum wage and part-time hours allowed. He next got a job at McDonald's and worked so hard he was pegged for management training.

Then McDonald's management noticed he was putting in 80 hours a week, taking double or triple shifts whenever someone quit or called in sick.

"I never say no to work," Luangkhot says. "But they said I worked too much. They cut my hours from 80 to 24 hours a week. I thought, 'OK, time to look for a new job.' "

An acquaintance told him about a job scooping ice cream at Maxim's, the upscale New York restaurant. "I thought, 'I can do that,' " he recalls. "So I started a new life."

He was on his way to the world of pastry, guided by Maxim's pastry chef, the late Jean Marc Burillier.

At first, scooping ice cream was all he did.

"Jean Marc said he was interested in me because I work hard in whatever I was doing. He asked me if I wanted to learn pastry. At first, I say no. I wanted to be a busboy because the busboy makes more than ice cream scooper."

Burillier, however, insisted on teaching him to make pastry and desserts.

"He said one day I will understand."

Luangkhot began with cookies, then more complex desserts, like souffles. The two worked together for several years, until Burillier moved on to Tavern on the Green. Luangkhot went to work as a pastry assistant at the Peninsula Hotel, rejoining Burillier when the chef opened a new cafe, Trois Jean.

Soon Luangkhot had a yearning to open his own bakery. He explored different cities and settled on Honolulu in 1994.

"I looked around at the price and the quality of pastry and I thought Hawaii still needed a quality bakery.

His first venture was a shop in Aiea, but with a high lease and a customer base too far away, "we couldn't make it."

The day he shut down the shop, the phone rang.

"I thought, OK, I take the last call before I close the door."

On the line was Chai Chaowasaree of Singha Thai restaurant, who was planning his new Chai's Island Bistro, and wanted Luangkhot to provide pastries and desserts. When told that the business was closing that day, Chaowasaree offered Luangkhot a job.

While working with Chaowasaree, Luangkhot began a wholesale dessert and pastry business. Although things were going well, he still wanted his own shop.

"My old customers stop me on the street and ask if I open another bakery. But I have to first get over being scared. My first business fail and I don't want to fail again."

Still, he believed he had a better product than what was being offered around town. When the Kaimuki location became available, he "got over it," and opened his shop last March.

"It is a much, much better location," he beams. His customers, happy to have him back, help him not only through patronage, but with small favors.

One made him a scrapbook with photos of his products and his friends. Another designed and produced a list of his menu while another designed his gift certificates. Still another brings fresh flowers for his tables every week.

"They say, 'We don't want to lose you.' It makes me strong and makes me work hard."

Besides his wife, Daokeo, who works at the bakery part time, he employs two people, but does most of the work himself.

"I do all the baking. I am everything from the dishwasher to the decorator," he says happily.

"I never dreamed of this," says the father of two girls, looking around the shop. "I could never even conceive to be such a success."

"I came to the United States with nothing. But you have to hope. I had nothing, just a little chance. That's why I don't mind working 14 hours a day. If people are happy, it makes me happy. I don't feel tired if I am proud of what I am doing."

As for Burillier's refusal to give him the busboy's job: "Now I understand. And, I love it."

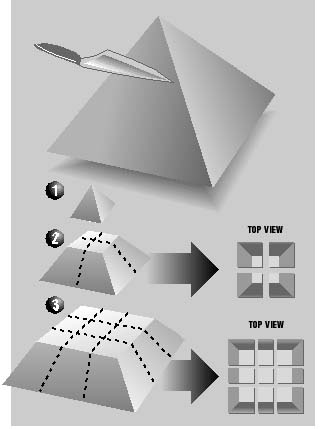

A step-by-step method for cutting a pyramid-shaped cake: Piece of cake

3. With a thin knife that's been warmed in hot water, cut off the peak; that

2. Next, make another horizontal cut, dividing the remaining dessert in half. Cut that layer into four pieces.

3. The last layer is cut into nine pieces.

Cardboard mold

Star-Bulletin

is basis of cakeBuilding a pyramid Praseuth Luangkhot's way is simple, but the results are as spectacular to the palate as the Egyptian pyramids are to the eye.

He uses no special molds or fancy equipment, just cardboard and Scotch tape.

First, Luangkhot cuts cardboard into four triangles of equal size, then tapes them together to form a pyramid. The cardboard mold is inverted into a bowl that holds it level. Next, he fills the point of the pyramid with mousse, then places a thin layer of cake, cut into a square to fit. Then comes more mousse, another layer of cake, mousse, cake, mousse, cake, until he has the desired number of layers. He finishes the base of the pyramid with a cake layer.

The pyramid is chilled overnight until the mousse is set.

To unmold, he runs a knife warmed in hot water along the planes of the pyramid, then inverts the mold onto a tray. An easier way would be to invert the pyramid, remove the tape and pull the cardboard away.

Let the pyramid sit for about 15 minutes at room temperature before cutting.

Luangkhot finishes his dessert with a dusting of extra brut (bitter) cocoa powder.

He can make the pyramid in any flavor the customer wants, he says. He sometimes adds a layer of raspberry sauce between cake and mousse, or uses a white or yellow cake instead of chocolate.

"It can be whatever you want."

Luangkhot says a 7-inch-high pyramid will serve 14 people.

Click for online

calendars and events.