Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

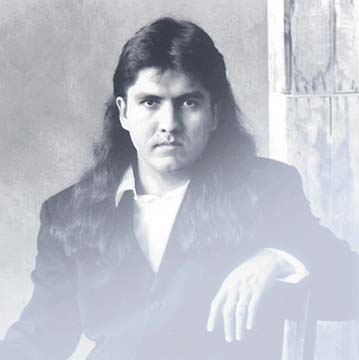

Man & myth

Acclaimed author Sherman Alexie

By Cynthia Oi

aims to kill the myths surrounding

Native Americans

Star-BulletinSHERMAN Alexie is arrogant. But he says he was that way even when he wasn't a famous writer. Alexie is talented. He has been heaped with praise critical and popular, and award after award.

He is versatile. He writes poetry, novels, short stories, essays and screenplays.

Alexie is funny. His conversation crackles with laughter, even when he's being serious.

Sherman Alexie is a happy man.

"Oh, god, yes!" he revels. "I have all sorts of books and movies going, critical attention, money -- it's all going pretty well."

But he doesn't know how long all of this will last.

At 33, Alexie has made a place for himself in both literary and Hollywood circles.

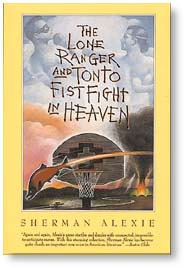

His 1998 film, "Smoke Signals" (based on his short story "This is What it Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona," from the collection, "The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven"), won acclaim at the Sundance Film Festival and in mainstream distribution.

SHERMAN ALEXIE EVENTS

Lecture: "Killing Indians: Myths, Lies & Exaggerations," 7 p.m. tomorrow, Campus Center, University of Hawai'i at Manoa. Free, presented by UH Distinguished Lecture Series. Information, 956-5666

Workshop: "Screenwriting: The Creative Process," 10 a.m. to noon Thursday, Yukiyoshi Room, Krauss Hall 012, UH. Free, Pacific New Media, Outreach College noncredit course. Information: 956-7221

He has just finished a screenplay based on Norman MacLean's "Young Men and Fire" for Warner Bros. and is working on another called "I'll Take Manhattan," also for Warner Bros.

Another short story collection, "Toughest Indian in the World," will be out in May.

The Spokane-Coeur d'Alene Indian who grew up on the Spokane Indian Reservation in Wellpinit, Wash., is in Hawaii to present a lecture and a screenwriting workshop.

It is his second visit to the islands. He and his wife, Diane, spent part of their honeymoon on Lanai, where he was struck by the contrast between locals and tourists.

"Lanai reminded me of India or some country with a rigid class system," he says.

Staying in an upscale resort "was so strange for me and my wife -- to be there with all the tourists, the haoles, who looked one way while we looked more like all the people who were the waiters and the fishermen and the divers."

Marveling at "the amazing diversity of brown skin" in Hawaii, he says his lecture, entitled "Killing Indians: Myths, Lies & Exaggerations," will be relevant here.

In his mind, Hawaii and America aren't united.

"Just because the U.S. has colonized Hawaii, I still think Hawaii belongs to itself. I don't think of it as part of the United States, even though it is. It's supposed to be its own country, really."

Alexie talks like a man who doesn't put up a facade. This thing about being arrogant, for example, is offered without prompt.

"All of this success -- it wasn't necessarily overnight that all this happened," he says.

He approaches writing as a businessman would operate a business. "I think all too often people think the creation of art should not be structured, but it should. I firmly believe in that, and I think it's why I'm so successful."

At "successful," he laughs. "That sounds arrogant, but I was arrogant before so it's hard to hold that against me now," he says.

Alexie grew up poor on the reservation. He was born hydrocephalic and was not expected to survive. At 6 months old, he had brain surgery; doctors thought that at best he would be retarded. He was spared that, but not the alcoholism that gripped him for five years later in life. At 23, he regrouped and found in writing a sense of himself. Ten years later, his head is screwed on tight.

Alexie will not give in to the guilt syndrome that others may try to lay on him.

"All too often, when you're a member of a so-called minority group, the other members expect you to do things for them just because you're successful," he says. "But I grew up with nothing. It's not like I was born with privilege. I earned it, worked very hard for it."

He chooses to be responsible, however.

"I present my life as a possibility. I try to give people hope and faith in themselves. It's not owing, it's my choice to do for others, not guilt."

For his talk on screenwriting, Alexie has "no idea what I'll tell people."

"It's always difficult for me to talk about my writing process because I don't necessarily know how it is I do what I do. I sit down and write. That's how it works."

He reads "everybody and everything -- from Joseph Conrad to Agatha Christie, poetry, mysteries, sports books, comic books. If there are words on the page I read it."

He reads Tony Hillerman even though he objects to the white author using Navajo as his main characters.

"I don't mind if a white person writes about Indians. It disturbs me when somebody like Tony Hillerman has made this whole career around writing about the Navajo because he ends up being the person people turn to to learn about Navajos rather than the Navajos themselves. He becomes the substitute, the expert by proxy."

What such writers produce is what he calls "colonial literature."

"Everywhere else in the world, it is considered such. In South Africa when a white South African writes about black South Africans, it's defined as colonial literature. The only place in the world it's not called what it is is in the United States.

"Tony Hillerman is a good mystery writer, his books are good. But it's still colonial literature; Barbara Kingsolver also writes colonial literature.

"White artists somehow believe that their art lifts them above the politics of their race," he says.

None of this is said with anger or resentment, but with honest examination.

He looks at himself in the same light, well aware of his good fortune, wondering how long it will last.

"I think writers have shelf life," he says. "We only produce quality work for a limited period of time.

"I don't know how long that is for me -- 10 years, 20 years -- I don't know. I love to tell stories, but who knows how my life will change," he says.

Alexie's habit is to write the last sentence of each story before anything else. "If I don't have the last sentence, I don't have the story," he says.

What ending would he write for his?

Click for online

calendars and events.