Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

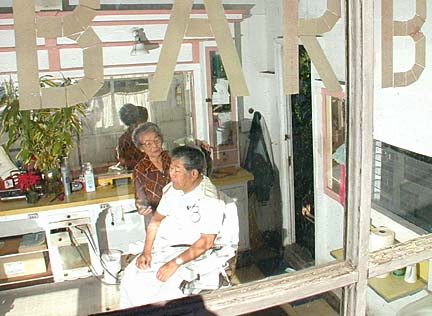

Eighty-six-year-old barber

Katherine Nakamura is closing her shop

and saying aloha to the customers

who gave her...

By Cynthia Oi

Star-BulletinIF you don't know Katherine Nakamura and see her tooling down the H-1 from Kapahulu to Liliha in the morning, you likely won't be able to distinguish her from thousands of other older women who quietly go about the business of living. Women who grew up in a society so altered that younger women -- while knowing intellectually that things were different in the old days -- may not really understand how different.

Nakamura retired today, one of many others who chose to end the year with change. She shut the doors of her barbershop on Liliha Street, ending more than six decades of wielding scissors, clippers and combs.

She is 86 years old. "How do you like that?," she asks, as if disbelieving the number. She laughs heartily, her hand covering her mouth. Like the gesture, Nakamura's life story is familiar among nisei women.She grew up on her parents' farm in Kaneohe, the oldest of four children, and left school after 8th grade.

"I didn't go to high school, you know. Olden days. My parents were farmers and there was no money."

She was sent to live with a barber and his family, supposedly to apprentice the trade, but for years, she worked as their house maid instead.

"We used to babysit, clean the house, wash the diapers," she says of the four other girls and a boy who boarded with the barber. "We used to work from about 6 in the morning until about 10 or 11 at night. Only after many years, the barber finally began to teach us."

The exploitation doesn't register in her explanation; that was the way things were.

Eventually, she went to work in a shop on Beretania before buying the business and operating it until the downtown building was torn down. Thirty-five years ago, she moved to Liliha Street.The barbershop there is tiny and old. Termites have dined on the built-in cabinets that hold clippers with steel surfaces burnished by constant use and shears still sharp and shiny. Yellowed stuffing puffs from holes in the leather of one of the two barber chairs. Paint peels from the benches and stools and from the building's facade. Although three different generations of linoleum covers the floor, it is swept clean, the shelves and glass panels are dust free and the good barber chair is spotless.

As she talks, Nakamura stands with her arm draped over the back of the good chair, the position seeming as natural as breathing to her. "I'm so used to standing up, I forget to sit when I eat at home," she says.

There is no sign for the store. It blew off during a wind storm a couple of years ago and she didn't bother to put it back. There is also no phone in the shop. Nakamura doesn't take appointments because "then people come in, cut hair and leave. I want people to visit."

Visit they do. There is a constant stream of customers, friends, neighbors and passersby.

Jean Kam pokes her smiling face in the door to say hello on her way to church. She asks if Mrs. Nakamura enjoyed the pickled vegetables she made.

"Oh, we really enjoyed that," Nakamura tells her. "That was good, good one."

They talk about how different things will be when the shop closes.

"I'm going to miss her," says Kam, shaking her head. But not wanting to be sad, she blinks and her smile is restored. "You know why? This is my resting spot. Where I going to rest now?"

They laugh and exchange compli-ments: Mrs. Kam's namasu, Mrs. Nakamura's microwave mochi, Mrs. Kam's good bowling, Mrs. Naka- mura's skill with the scissors. They go on and on as if they need reasons to explain their friendship.

Walter Yamashita bustles in after Kam heads off. He has driven in from Wahiawa for his haircut, but like all of Nakamura's customers, he gets more.She laughs at his jokes and funny stories. Then she listens attentively as he talks about his job, his family, his ex-wife. She asks him questions that prompt him to examine a problem from another point of view; she sympathizes and urges him to be sympathetic.

All the while, her murmuring and her nimble fingers shuttling the scissor blades over his head soothe him. She deftly shapes his hair, working from forehead to sides and back like she has probably done a hundred times since the first time she cut his hair more than 30 years ago.

In a few minutes, Yamashita is transformed. While his hairline has taken on a trim edge, his face has lost its tension, the furrows smoothed from between his brows. He says he'll go to Nakamura's house for haircuts after she retires and although he laughs, he's half serious. "Kay-chan," he says. "I even follow you to the graveyard to get haircut."

She gives his shoulder a shove, covers her mouth and laughs. He is sent away with a gift, wrapped in a plain brown bag with a felt-penned note that reads "Thank you very much."

Nakamura was widowed at age 48, her husband James taken by cancer. She was left with four children to raise. She doesn't wear the badge of "single mother" and all the current "isn't-she-a-strong-woman" kudos that come with it.

"I had to do what I could. I worked hard, took in laundry and sewing, cut hair. I wanted my children to go to college, get an education, not like me. Even my grandchildren are well educated."

She put food on the table, disciplined the two boys and two girls, made clothes for them, and paid off the mortgage on the Kapahulu house she's lived in since 1949.

"Now my children want me to retire."

Three of them have preceded her, she laughs. Jean was a registered nurse, Jane a school teacher and Bert worked for the phone company. George, the youngest son, still works at Wang Government Services.

He worries about his mother driving to and from the shop six days a week. He also worries that it's her interaction with people every day that keeps her vital.

Nakamura isn't worried. She is looking forward to doing her patchwork, crocheting and sewing. She'll have time to take walks for longer than the half hour she allows between rising at 5:30 a.m. and getting to the shop at 8.

She doesn't think she'll sleep in late, though. "No matter what time I go to sleep, I get up by 5 o' clock, 5:30. It's a habit, I guess."

All through the morning, Nakamura cuts hair, talks story, accepts mochi and treats from friends, tells frantic postal customers that the mailman came early but he still might be down the lane. Most of her visitors are older women, sharing the latest news about their families, grumbling about cousins who went to Hong Kong and counting the days until her retirement.

When one asks if she wanted something more in life, Nakamura quickly and firmly shakes her head. "I'm glad all my children went to college and graduated. I'm happy that they are good. I have eight grandchildren and five great-grandchildren." These are her accomplishments.

"I told them as long as I live and as long as I can, I just want the holidays -- Christmas, New Year's, that kind holidays -- to be at my house. So we do that. I have a good group, they all are a good group."

Nakamura acknowledges that her life hasn't been one of luxury and ease, but she didn't expect it to be. "I'm not the only one who had to work hard, you know. Many people work hard, lot of ladies. I'm just ordinary."

An ordinary barber who not only cuts hair but soothes lives, an ordinary woman who, like many, are distinguished in the brilliant light of those who know them.

Click for online

calendars and events.