A University of Hawaii research team led by oceanographer David M. Karl has found evidence of life in one of the harshest environments on Earth -- a discovery which suggests that life could thrive in extreme environments elsewhere in the solar system.

Karl discovered bacteria in Lake Vostok, a freshwater, subglacial lake about the size of Lake Ontario that exists thousands of feet below the Antartic ice sheet.

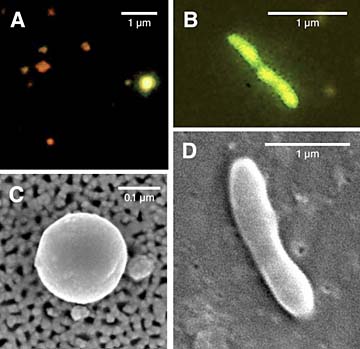

He found the microbes in a fragment of "accreted ice," believed to be liquid water from the lake that froze and was recovered in an ice core.

Tests of the melted ice water by his group showed the bacteria were viable cells. He believes they were living in the lake and became trapped in water that froze to the bottom of the glacial sheet. As a result, he said, "These accreted ice data suggest that Lake Vostok may also contain viable microorganisms."Lake Vostok has attracted international scientific interest because it may contain remnants of the Earth in an ecosystem that evolved over millions of years. It is believed to be the closest habitat on Earth to an ice-covered ocean on Jupiter's moon Europa.

The UH team's findings and those of a colleague, John C. Priscu of Montana State University, will be published in tomorrow's edition of Science magazine. The cover story in this week's EOS, the American Geophysical Union journal, also is about the Hawaii scientists' Lake Vostok research.

Both scientists concluded that the lake may have a potentially sizeable and diverse population of bacteria, indicating it can support life in an extremely cold environment without abundant nutrients and light.

"Our research shows us that the microbial world has few limits on our planet," Priscu said. "People may say, 'What is an oceanographer doing in Lake Vostok?' " Karl said. "My motivation is to look at life at Earth outposts, extremes of life, extreme habitats. "

Among Earth's oldest

Karl said the lake has been covered by ice for about 10 million years. "So, regardless what we find there, it's old by definition and may be the oldest habitat on Earth that's not been in contact with the open biosphere."He said this "makes it very exciting for diversity and evolution of microorganisms -- changes that have occurred living in extreme environments."

Lake Vostok is the largest and deepest of nearly 80 subglacial lakes discovered and mapped with airborne radio-echo soundings and other techniques.

Scientists believe the fresh water is kept liquid by the pressure of overlying ice and possibly geo-thermal heating.

Karl said the subglacial lakes of East Antarctica "could serve as terrestrial analogues to guide the design of samplers and experiments for life probe missions to the ice-covered ocean of the Jovian moon Europa."

UH planetary scientist Tom McCord said, "The search for life in extreme environments is showing more and more that life can live in places we never thought of before, and this (work by Karl and Priscu) is an important demonstration of that point."

McCord said Lake Vostok's environment in some ways is quite similar to what scientists expect on Europa, "with liquid water beneath a thick ice cap where heat to keep water liquid might well be geothermal -- heat from Earth at the bottom of the lake -- which is what is going on at Europa."While there is strong evidence of bacteria in the lake, Karl and Priscu said they don't know if the "accreted ice" is similar enough to the lake water to conclude that a similar, larger or more diverse population might thrive. "We don't know how "lake-like' this accreted water is," Karl said.

Find raises many questions

And there are many other questions, he said: "What kind of bacteria? What are they doing there? How many? How do they react with the geologic setting? Is the population decreasing over time and we're just seeing a few cells hanging around and living off death products of other cells?"Karl said the number of bacteria collected was 10 to 100 times lower than even the deep sea, which is one of the most sterile and hostile environments on Earth. "It looks like one of the strategies for life to exist in an extreme habitat is to reduce the population numbers," he said, speculating that organisms may be living off carbon from millions of years ago. "We may be looking at the end members of survival after up to 10 million years on Earth." Further studies may yield clues on strategies bacteria evolved to survive, he said.

A team of Russian, U.S. and French scientists last year completed drilling an ice core 11,700 feet below the surface of Vostok but stopped about 393 feet above the liquid water to avoid any material contaminating the lake.

Karl said a sample of the lake's sediments is needed to "tell us something about the evolutionary history of the lake, and possibly of the Antarctic continent."

Another big reason to go into the lake, he said, is that Antarctic ice cores have provided a climate record of more than 400,000 years and sediment samples could extend that to millions of years.

But the project is on hold until potential contamination problems can be resolved. The drilling team stopped above the liquid water and backfilled the hole with antifreeze and diesel fuel to keep it for future use if needed, Karl said. Because of that, he said, scientists suggested the lake already may be contaminated from seepage.

"That's where the whole issue is sitting because Antarctica is such a special place, such a precious place, we don't want to justify contamination just to justify science."

Contamination also is a significant issue in exploring Europa, McCord said. "How do you sample the ocean without contaminating it, and I don't know...With Europa we have a good chance to answer what I consider the most important scientific question: Can life form outside the Earth? To screw that up by contaminating it would be the crime of the millennium."

Members of Karl's research team are D.F. Bird of the University of Quebec, Montreal, and Karin Bjorkman, Terrence Houlihan, Rachel Shackelford and Luis Tupis of UH-Manoa.

UH student newspaper

Ka Leo O Hawaii