Advertisement - Click to support our sponsors.

Khewhok has art world

By Suzanne Tswei

at his fingertips

Star-BulletinARTISTS who are paid to paint portraits know they must present their subjects in the most flattering light in order to keep the job. Artists painting their own portraits can do whatever they wish to their own image.

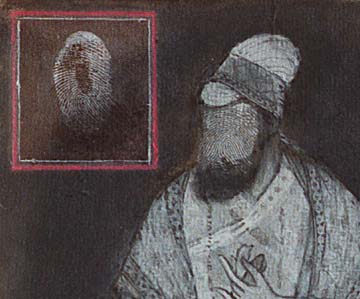

In Sanit Khewhok's latest series of self portraits at Ramsay Galleries, the Thai native appears as anything but himself. In one image, he is an Englishman posing with a dog. In another, he is the Roman Sun King. Or he is not even human; he is an owl. And his face is a blur in all of them.

Upon closer inspection, though, you can see that the blur actually is a fingerprint (from his right forefinger.) At 51, Khewhok is perfectly content with his face but he thinks his finger print is far more intriguing as a metaphor for his identity. (Earlier self portraits are realistic renderings of his face.)

AT A GLANCE

What: "I.D.," recent works by Sanit Khewhok

When: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday

Where: Ramsay Galleries

Cost: Free

Call: 537-2787

"I was interested in the meaning of identity. What is the ID of a person? People know us by our faces. But if you can't see the face, then who are you? How do other people see you?"

A person's face isn't necessarily a mirror of the person, he says. The face can be altered by plastic surgery, which is continues to increase in popularity. The face can contain only the information the owner wants to show.

"But the fingerprint, you can't change. Fingerprints are more authentic than the face" he says.

Khewhok's self portraits may show him as European royalty, but he isn't a man interested in titles or social positions. He simply was interested in painting the elaborate and voluminous costumes. And he likes the patterns of the lines in the fingerprints.

"I am inspired by Western and Eastern paintings. I started in the western tradition. In western art, it's about volume (as in the three-dimensional qualities of the costumes.) In Eastern art, lines are more important."

Khewhok became interested in art as a child, influenced by his mother and maternal uncles who all dabbled in art. By the time he was 15, he was painting huge billboards that advertised movies. Later, he served as the curator of modern art at The National Gallery of Bangkok.

His formal art training was in the Western tradition. He studied painting, sculpture and printmaking at Silpakorn University in Bangkok before going to Rome on scholarship to study painting and restoration techniques. He took up Eastern art on his own later.

In 1986 he moved to Honolulu, where he works as collections manager at The Contemporary Museum, after he had met and married his American wife, Carol.

He said he was too Westernized and rebellious when younger to have been interested in anything Eastern. For the same reasons, he delayed serving as a Buddhist monk, a coming-of-age rite. Generally, Thai men who reach age 21 enter a monastery to train as monks for three months. Khewhok waited until he was 40, and the experience changed his art making forever."It's training you to face the world," says Khewhok about the monastery life of meager food and little human contact. "I went to a small temple. The only thing (I was expected to do) was meditate all day and all night." At first, he had trouble adjusting.

"What happens is you get very sleepy (everytime you try to meditate.) Or you get a big headache. It's from the tension (of having to concentrate on meditation.) You don't know how to do it right."

To help relieve the tension and the monotony, Khewhok collected twigs and stones from the ground as he circled the temple grounds in his effort to meditate. He selected materials for their interesting shapes and colors, and smallness. Art making was not allowed, so he worked with things small enough to be hidden from the master monk.

Working with the found objects freed him from his strict Western art training. He learned to invent his own rules, which have served him well since. Even if he hadn't discovered new grounds for art making, Khewhok still describes his monastery training as an "exceptional experience."

He learned to build a small hut, which served as his sleeping quarters. The hut had no walls, but it was raised on a platform so the snakes wouldn't crawl in at night. He learned to look inward, and became more aware of his own being, emotionally and physically.

"I would do it again if I could," says Khewhok, but he has no plans to return to Thailand for now.

Click for online

calendars and events.