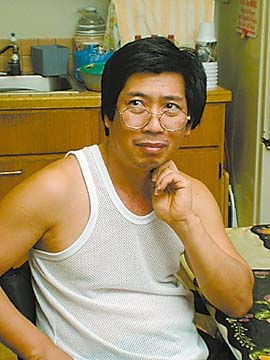

Arsenio 'Sonny' Magday

By Rod Ohira

was left waiting in ER while a

blood clot in his spine left him

paralyzed from the

waist down

Star-BulletinEsther Magday often dreams that she, her husband and 6-year-old son are walking to the park on a Sunday.

"All of a sudden I wake up," Magday says.

The wheelchair next to her husband of 10 years tells her that strolls to the park and zoo are gone forever, though Arsenio "Sonny" Magday hasn't given up hope of walking again.

"I'm expecting a miracle," says 45-year-old Sonny Magday, who will receive $4.3 million cash from an out-of-court settlement with Straub Clinic & Hospital for medical malpractice. The settlement was to be announced at a press conference today.

The lawsuit filed by attorney Richard Fried Jr. alleges Magday waited six hours in Straub's emergency room for magnetic resonance imaging of the spine to be approved. The MRI detected a blood clot in the spinal cord, and surgery was performed two days later.Magday was left paralyzed from the waist down.

It was the pressure on the spinal cord, which was allowed to go unrelieved for hours, that caused the permanent damage, says Fried.

The attorney added, "We had the case reviewed by the chief of a major neurosurgical department on the mainland and another prominent neurosurgeon, and both issued reports stating that had the MRI been obtained shortly after his arrival, a simple surgical evacuation of the blood clot could have been performed that would have resulted in complete or near complete resolution of his paralysis."

Sonny Magday, who came to Hawaii from the Philippines in 1983, held down two jobs and 62-hour weeks before becoming paralyzed.

As a full-time maintenance worker at Tropic Seas condominium in Waikiki since 1983 and a part-time employee in food services at Straub Hospital for the past 14 years, Magday recalls being absent from work only once or twice in 16 years.

"Even though I sick, I always go work," he said.

Magday awoke on Sept. 4, 1996, with a bad headache and back pain. He left his then-Maluna Street residence in Salt Lake and caught the 5 a.m. bus to his Tropic Seas job.

While mopping at 7:30 a.m., Magday felt a severe pain in the middle of his back.

He recalled the "pain was going up to my forehead. I felt like something was sucking my eyes."

'I trusted them'

Unable to continue working, Magday called his wife and then caught a bus to Straub. By the time he reached the emergency room at 8:43 a.m., Magday was experiencing numbness from his waist down and could barely walk."I went to Straub because it was the closest hospital and because I was working there and trusted them," he said.

An emergency room doctor and physician assistant noted Magday was complaining of severe back pain; numbness, tingling and weakness in both legs; feeling as if he couldn't walk; and numbness from the lower rib cage down to his toes.

Also noted in the ER record was Magday's inability to lift his legs off the gurney and a comment that he felt paralyzed, Fried says.

The ER doctor, who has over 10 years' experience according to Fried, asked Magday to stand. He tried and fell.

Magday was assisted back onto the gurney, where he stayed for nearly six hours.

The ER doctor testified at his deposition that he thought Magday needed an MRI, but it was Straub's policy that requests for an MRI need approval from an on-call specialist, says Fried.

The ER doctor contacted the consultant, who was on Maui seeing patients.

"For reasons that remain unexplained," says Fried, "it was decided that nothing further should be done until the consultant returned to Oahu later that afternoon to examine Sonny himself."Straub ER records, provided by Fried, note that at 11:35 a.m. Magday stated to a nurse, "I can't stand the pain anymore." At 1 p.m. the nurse wrote he was crying and moaning in pain.

"I kept asking what time the doctor coming, and they just say the doctor on call," says Esther Magday. "We felt trust that they doing the best they could."

Sonny Magday recalls yelling out repeatedly, "'Help me; where's the doctor?' but they just ignoring me."

It was after 2:30 p.m. when the MRI doctor looked at Magday's case, says Fried.

Under "history of present illness," the consultant wrote the following notation on his chart: "The patient was sent up from the emergency room because of possible malingering."

"All I know is, he got it from somebody in ER," Fried says of the statement. "It's unbelievable."

'No sorry, no nothing'

By the time Magday was examined by the consultant, he had no reflexes or motor and sensory functions below his waist, says Fried.Magday spent 10 days in the hospital following his Sept. 6 surgery before being transferred to the Rehabilitation Hospital of the Pacific, where he stayed for a month.

While at Straub, Magday says a doctor told him "not to worry, you can be walking in six months to a year.

"Nobody says anything else -- no sorry, no nothing. They didn't feel what I felt."

It was in rehab that a physical therapist told Magday he would not walk again.

"I feel no hope," he recalled. "I said to myself I going be handicapped forever. I started thinking of killing myself."

Magday had to move out of the two-story Salt Lake home that he, his mother and sister had purchased, because it was on a hill.

"I couldn't get around in a wheelchair, and when we had to go some place, they had to carry me down to the car," says Magday.

In June 1997 the family began renting a small, bottom-floor unit in a two-story house on Uhu Street in Kalihi. It is located at the back of the house, and the walkway is barely wide enough for the wheelchair.

With his wife at work and son at school, Magday sat in his wheelchair, never venturing outside.

"I can go nowhere unless somebody push me, so I only watch TV, read the Bible," he recalled. "I feel badly because I cannot sit down for long hours.

"After the first year, I accepted I had to learn a new lifestyle. I like to cook, but the stove and counter is too high for me. I can't bathe myself. I cannot even use the bathroom without a special wheelchair."

The financial settlement to be paid by two Straub insurance carriers has helped to put a smile back on Magday's face.

"It's a big help to know that my kid can go to college," he says. "For me, we can go ahead. What happened is now over."

Fried says the family has purchased a special vehicle that Magday will be able to drive.

"It's fair," Fried says of the settlement. "He'll need a lot of future nursing care and a designed home that's wheelchair accessible. We're also setting him up with a financial planner."

Unlike most out-of-court settlements, Fried and his client did not agree to a confidentiality clause.

"We felt it was important for people to know what happened," says Fried. "Generally, Straub provides fine care.

"This is an example of an isolated case that can occur. The physicians didn't take the complaints seriously. But it shows that patients also need to assert themselves more if they feel complaints are not being addressed."