OAHU'S LAST BEACH SETTLEMENT

Some families have spent years

By Gordon Y.K. Pang

at Keaau, Oahu's last beach friendly

to the homeless, but the city will

rout permanent camps Dec. 1

Star-BulletinLorin Firm puts down the rake she's been using to sweep her front yard and invites the visitor to sit on a chair in her back yard.

For Firm, her front yard, back yard and living room are the same grassy area fronting Farrington Highway. To the side are two tarps -- one that's her kitchen and pantry, the other her bedroom.

She apologizes for not offering a drink, but her family has "run out of ice for the week."

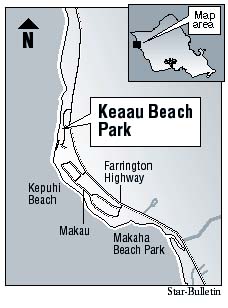

Firm, her boyfriend and teen-age son are among the roughly 35 families living at Keaau Beach Park. Where permanent tarps once sprinkled the Leeward Coast from Kahe to Kaena points, Keaau is the last beach available to the homeless.

But not for long.

The Keaau families must be out by Nov. 30, City Parks Director Bill Balfour said last week. There will be no extension of the agreement made in April allowing time for families at the beach to work with social service agencies to find permanent homes.Come Dec. 1, Balfour said, "With police assistance, we need to enforce the rules and it is our intent to do that."

The city can't keep the homeless off the beach at Keaau entirely.

But like everyone else, they will be required to get camping permits two weeks in advance, as is the policy at other city camp sites.

And even more critical for those on the beach, they will have to break camp every Wednesday and Thursday -- requiring them to find shelter elsewhere on those days.

Like most everyone else at Keaau, Firm doesn't know what she'll do when that day comes. And like most everyone else at Keaau, she has a story to tell.

She worked in Waikiki hotels waitressing and bartending for much of her 50 years. But she got hurt on the job, she said, tearing the ligaments in both her ankles.

Firm tried to continue working labor-intensive jobs, but her legs would not hold up.

Other employers, she said, are wary of hiring her because of her injuries.

She makes bead and shell necklaces and slippers that she sometimes sells at craft fairs. She also helps maintain the area around her camp and those of the families nearby.

Sure, Firm said, she'd prefer to be in a regular house with a roof and four walls, but for now, home consists of two tarps and a truck. And she will take issue with anyone who deems her a bum on the beach.

"They got to live this life first before they say anything," she said, her pleasantness disappearing for a moment.

A generation on the beach

The sight of people living on the beach has been a part of the Waianae Coast for years.Waianae Community Outreach coordinator Stanlyn Placencia says it's a generational issue for some there. Some may be so used to living on the beach that "it's hard to live within a structure of walls where you have close neighbors."

Glenn "Keola" Ah Nee, who says he's been living at Makua and Keaau for several years, fits that description.

Ah Nee said he was born on Mokauea Island and has slept at the beach by choice for most of his life.

"I'm like my ancestors," he said. "I'm one with the elements."

Whether there by choice or necessity, the homeless at Keaau are out of options.In April, Balfour agreed to allow Placencia's group to conduct a pilot project at Keaau. The parks chief stepped in after repeated complaints dealing primarily with loose dogs belonging to the homeless that were harassing park visitors.

The agreement allowed the homeless to stay at Keaau without interruption through Nov. 30.

In exchange, Waianae Outreach and other social service agencies were tasked with helping families "transition" off the beach and into permanent housing.

Before the agreement, the homeless and everyone else were required to break down their tents and pack up their belongings on Wednesdays and Thursdays to allow cleanup of the facilities.

Other days, those agreeing to join the project promised they would clean the park.

Of 17 families identified in April, 12 have moved out, Placencia said. Most have been placed in rental situations or transitional housing, or moved in with relatives or friends.

Placencia says she hopes to have the other five taken care of before Nov. 30.

Since April, however, some 20 to 30 other families have joined the original 17 at Keaau.

Campsites at Keaau grow

Some moved over from other beaches last month after the city conducted sweeps along the coast from Kahe Point to Pokai Bay.An estimated 75 people were displaced during the sweeps, although no one seems to have a clear fix on how many sought refuge at Keaau.

Placencia and others believe what further exacerbated the camps' population was the onset of a new policy at the state Department of Human Services.

The department has started cutting off the welfare checks of families that fail to meet work requirements. Families began losing their checks last month.Department official Kris Foster said about 200 out of 6,000 families are now categorized as noncompliant.

Besieged by all the families now on Keaau, the undermanned Waianae Outreach group cannot provide comprehensive case management and servicing for all of them, Placencia said.

Outreach pulling back

While some help has been offered to the newer families, the group is pulling back."It took a toll on us. We need a break to try to revive ourselves," Placencia said.

Balfour, meanwhile, is firm.

"We have rules and regulations that we operate under," he said. "This was a very noble experiment that worked relatively well. But now we're dealing with a whole new group and this just can't go on forever.

"This can't be a permanent social services type deal. This is a park, and the people of the City and County have the right to enjoy the park and not have to deal with people who are there on a permanent basis."

Donna Tinoga, whose family lives in tarps next to Firm's, has awakened from a nap. She walks over to Firm's lawn and sits on one of the folding chairs. The two women admire a plant that graces a lawn table.

Tinoga and her family have been at Keaau for about six years, about as long as anyone else living at the beach.

She leads a congregation in prayers on Sundays.

While the media has focused on drug activity on the beach, Tinoga said, "I see a lot of things happen here for the good."

At one time, her family had a roof over their heads in Makaha.

Tinoga said one word describes what happened: "Drugs." But her family has since found God and is on its way to recovery, she said.

Her 23-year-old son just got a job, and both she and her husband are "still plugging away, going job-hunting."

Tinoga said she doesn't think her family or others will be forcibly removed.

"They're not going to move us from here because there's no place for us to move."

Many once had a home

Danny Manning, 84, said he and his wife were left without a roof over their heads when they got into a dispute with their Maili landlord."Look where I sleep," Manning said, pointing to a van filled with clothing and bedding. "I've got to find a house. I don't want to live like this."

But like others on the beach, Manning said there is an ohana feeling, with people giving each other food and watching out for one another.

Carol Boyd, originally from Makawao, said her family would not have even ended up on Oahu if not for the fact that her daughter, now 6, needed hospitalization.

The child's expensive medical bills left the Boyds without rent money, and they ended up at Keaau, where they've been for six years now.

Robert, 35, and wife Pat have lived on the beach since July.

They once had a home in Waipahu, but hard times hit and "I lost my job and stuff, we couldn't pay the rent," he said.

Drug trouble disputed

Some critics say many of those living on the beach are part of a drug culture fueled by people who come in from elsewhere only to make their deals.But those who live there say it's the teen-agers who congregate around their cars until late at night drinking and partying that are the biggest trouble at Keaau.

Tinoga gazes from where she sits under a tree and waves at a neighbor as he drives down Farrington Highway.

"Outside people judge us real quick," Tinoga said. "If they would get to know us, we're just like people who live in a house.

"We're just houseless."