MARIAN Szczepanski, 79, owes his life to hardheadedness, to his refusal, time and time again, to die under the Nazis:During 1-1/2 years at Auschwitz, where Germans murdered Jews and other prisoners in gas chambers, and by human experimentation, torture, forced labor and starvation.

Through the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, when Szczepanski and Polish underground fighters battled them for 63 days, only to see their city destroyed.

And as a German prisoner of war.

Szczepanski, a native of Poland who is staying in Hawaii with his son, never had any doubts he would survive. It wasn't luck, he says, but a fierce desire to fight back at an enemy that beat and almost killed his mother for selling meat to Poles, an item reserved for the Nazis."At Auschwitz, I said, 'Germans cannot kill me here.' I had hate and desire to avenge my mother."

The deep scars left by World War II leave Szczepanski feeling he has little to rejoice. Now an American citizen from Northville, Mich., he neither forgets the atrocities nor forgives.

"A united Germany equals a strong Germany. A strong Germany equals conquest, if not by military, by economic conquest," he said, distressed by the growth of German business in his homeland. "Let Germany live in prosperity and freedom, but let it not be united."

Szczepanski, who is not Jewish, admitted his is a lone voice in Poland. But there are few who survived Auschwitz, he said, and they are disappearing.

"I feel for him," said Bettina Mehnert, a German citizen who has lived here for 11 years. "I understand that he can't forget. I don't know if I could. But I can only apologize so much. It wasn't my generation."

Mehnert's grandfather spent seven years in a Siberian prison. "It was a terrible war for everybody."The persistent Szczepanski talks for hours to anyone who will listen about his war experiences. His son, Victor, a local roofing consultant, returned with his father to Auschwitz in 1970. "He doesn't want the world to forget," his son said. "When the dinosaurs like him all die, there won't be a voice to let people know what happened."

Szczepanski, a man with piercing blue eyes and bushy white hair, rattles off historic facts and quotes great philosophers to make his points. He carries a 15-pound notebook of frayed newspaper stories on his life. It holds photos showing him as shaven-headed prisoner No. 4974 at Auschwitz, where he was confined from September 1940 to March 1942; of him fighting alongside the 36th Infantry Division of the 7th U.S. Army, which liberated him; and later as a Polish soldier under the umbrella of the British Army.

'I was not guilty of anything

except being Polish. I and the

other Poles were subhuman

to the Germans.'Marian Szczepanski

NATIVE OF POLAND WHO IS STAYING WITH HIS

SON IN HAWAII; SZCZEPANSKI, 79, WAS IN A NAZI CONCENTRATION

CAMP AND WAS A PRISONER OF WAR IN GERMANYSzczepanski said he was first taken by the Nazis on Sept. 19, 1940, in a roundup of men in Warsaw. A 20-year-old student at the time, he was awakened early in the morning by his mother, who screamed, "Marian, Gestapo." They found him hiding in a cupboard, then beat him, his mother and sister. "I was not guilty of anything except being Polish. I and the other Poles were subhuman to the Germans."

In the next days, about 1,800 men were loaded into cattle trains and sent to Auschwitz, filled in the beginning with Polish inmates, he said. German criminal prisoners awaited them with clubs and attack dogs that killed anyone who couldn't keep up. They became "the masters of life and death."

He described beatings and torture -- heads were held under freezing water in fish ponds. Many starved. "Their job was to kill us," he said.

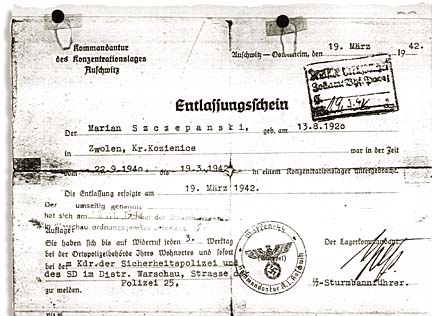

Five of 25 classmates from high school died there. Very few Polish men who arrived with him survived. He and 63 others were released at the same time but he doesn't know why; perhaps family intervention, or a way to spread fear in others who would hear their experiences.

Szczepanski carries copies of his release paper signed by the Nazi commander of Auschwitz, Rudolf Hoess (not Rudolf Hess, deputy of Adolf Hitler). Few such documents still exist, he says, and although he's been offered $10,000 for the document, "as long as I live I will give it to no one." It will go to the Auschwitz Museum when he dies.

After Auschwitz, Szczepanski joined the Polish underground and fought in the Warsaw Uprising: 63 days of ferocious battle against the Nazis. Szczepanski smuggled food, weapons and people through the sewers. Most of Warsaw was destroyed by the Germans, and he was imprisoned from October 1944 to April 1945, when he was liberated by American forces.Szczepanski later earned degrees in London as an engineer and metallurgist, then moved to Michigan, where he started a diamond tool company. He's spoken to groups around the world on his war experiences, conducted his own South American search for Nazi war criminal Joseph Mengele in 1971, and been a guide at Auschwitz.

Victor Szczepanski said his father asked organizers to be allowed to speak briefly at an August ceremony here marking the end of the war with Japan. He spoke of his fears about a strong Japan and Germany, which made program organizers uneasy but evoked applause from some World War II veterans.

"They were all people who suffered heavily," his son said. "It struck a chord in the veterans, although it might not be politically correct."

Unlike many victims of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima who are equally committed to sharing their experiences to prevent such warfare in the future, Szczepanski is not hopeful that his stories will prevent further genocide, pointing to the killing in Bosnia.

"We don't learn from history," he said. "In human nature there is cruelty."