Up, up, up! Buildings in centuries past didn't spurt up, they spread out. There's a sound engineering reason for that. Building construction was considered similar to wall-building: stack stuff up, lay a floor across it, build a roof. Buildings sprout skyward

The problem was the tensile strength of the materials, whether it was stone or wood. As more floors were added, the weight squeezed the material underneath, causing it to shift sideways or shatter. This was the reason that the great cities of the world averaged three stories in height.

Larger buildings either incorporated the sideways-squish into the design -- the pyramids of Egypt and Middle America -- or were braced against it -- the "flying buttresses" of Medieval cathedrals -- or used progressively smaller floors -- like the pagodas of Japan and China.

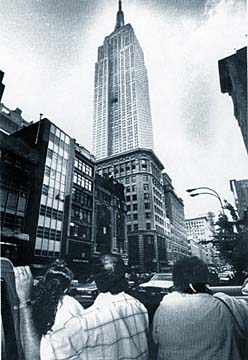

Then came cheap steel. Architects realized they could construct buildings with skeletons of steel, and go up virtually any height. "Skyscrapers" became a national craze in the early part of the century, and architects lavished personality into the buildings. Structures like New York's Flatiron and Chrysler buildings and the Empire State Building became emblems of soaring ambitions. And we won't even bring up the Freudian interpretations of these dream constructions of predomiantly male architects.

As cities grew up instead of out, population increased to critical mass. So much so that the primary urban-architecture concern of the last quarter of the 20th century has been the shifting balance of living and working space.

By Burl Burlingame, Star-Bulletin "Everyday Life" is a photo feature that examines the 20th Century. Send suggestions and reactions to EVERYDAY LIFE, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, P.O. Box 3080, Honolulu HI 96813, or features@starbulletin.com.

Click for online

calendars and events.