Meteorite hunter

from UH honored for

Antarctica workProgram yields clues to origin of solar system

By Helen Altonn

Star-BulletinWhen University of Hawaii researcher Anders Meibom found himself with three other men in the silence of Antarctica's ice desert, he said, "it was pretty amazing, like it's not really the Earth. It's so alien."

Meibom, 30, who studies meteorites at the Hawaii Institute for Geophysics and Planetology, recently was awarded the Antarctica Service Medal of the United States for his participation in a 1995-96 U.S. Antarctic Search for Meteorites expedition.

He spent seven weeks in Antarctica as a volunteer with ANSMET principal investigator Ralph Harvey of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, another volunteer scientist and a mountaineer to guide them.

"You don't just walk around because of crevasses," he said. "I had no experience prior to this."

The team was on a reconnaissance mission looking for meteorites for the National Science Foundation's Office of Polar Programs. Antarctica is known as "the world's premier meteorite hunting ground."

"These are rocks that were

in space since the solar system

was formed 4.5 billion years ago.

We're looking at

the first stuff."Anders Meibom

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII RESEARCHER"We went to places nobody has been before," Meibom said.

He said they found 250 meteorites -- such a high number that another expedition is being launched for a "foot search."

"These are rocks that were in space since the solar system was formed 4.5 billion years ago," Meibom said. "We're looking at the first stuff."

HIGP planetary scientists are among those who have received the extraterrestrial materials for research to try to understand the formation and composition of the solar system.

But Antarctic explorers can't just put rocks in their pockets and take them home, Meibom pointed out.

The U.S collection is stored at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, and material is distributed to meteorite researchers.

Meibom said a Navy C-130 transport plane flew the reconnaissance team and its equipment to a plateau behind the Transantarctic Mountains, dragging skis over the surface to find a level landing place.

"The plane was shaking like the inside of a blender," he said.

Once it landed, the plane drove at full speed along the ice with its back cargo door open so the supplies and equipment could roll out, he said.

"When the plane leaves, you're standing there looking at an ice desert. You hope everything goes right. ... The mountains are beautiful. Otherwise, there's ice cover. There's nothing."

Three times, Meibom said, the men had to spend five days in a row sitting in their 9-by-9-foot tent because of severe cold and winds. When storms hit, the temperature fell to minus 40 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit, he said.

They got through the days by reading and listening to shortwave radio.

"You've got to be very patient," he said.

But the expeditions are "a pretty expensive thing to do," he pointed out, "so as soon as the weather permits, you're out of the tent on Skidoos," traversing the field all day to scan for meteorites.

A small plane moved them and their camp to three different ice fields during the seven weeks, he said.

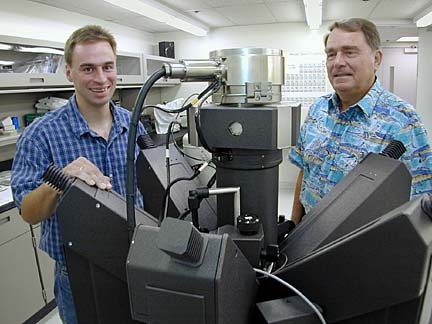

Meibom, formerly at the University of Odense, Denmark, joined UH two years ago as a postdoctoral fellow under a NASA grant to Klaus Keil, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology director.

Keil arranged a surprise ceremony for presentation of Meibom's award by Alan Teramura, UH senior vice president for research and dean of the graduate division.

Harvey, the ANSMET leader, cited Meibom's "cheerful and willing contributions to a scientific endeavor of enormous impact in the study of planetary materials."

Keil said Meibom "has an outstanding record. He is one of our young stars. We're always worried about young men like this. They don't stay with us long."

Would Meibom go again?

"I've got to talk to my wife first," he said laughing, noting they've had two children since his first encounter with the Antarctic.

Program yields clues

By Helen Altonn

to origin of the

solar system

Star-BulletinThe U.S. Antarctic Meteorite Search Program is "a poor man's space program -- a wonderful, wonderful program," says Klaus Keil, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology director.

In many ways, he says, it's today's Apollo program, producing primitive materials that are expanding knowledge of the birth and nature of the solar system.

The ANSMET program began about 15 years ago after the Japanese discovered large concentrations of meteorites on the Antarctic blue ice, Keil said.

It's a rich source of extraterrestrial material for several reasons, he explained.

Meteorites fall all over the Antarctic continent, he said, and they're buried in the ice and carried with it toward the coast at a rate of several inches per year.

Most meteorites fall into the sea with the ice, but sometimes obstacles below the surface block the ice flow and it piles up against mountain ranges, he said.

The ice becomes stagnant and is eroded by high winds carrying ice crystals, he said.

Deeper and deeper old ice appears at the surface and meteorites buried within pop out, he said.

Unlike white ice cubes in the refrigerator that contain air bubbles, old, exposed Antarctic ice is blue because it was under such extreme pressure that the air bubbles were squeezed out, Keil said.

He said U.S. and Japanese researchers have recovered about 20,000 meteorites over the years.

The more found, the greater the chances of finding unusual types, he said.

Most are from asteroids -- minor planets generally orbiting between Mars and Jupiter -- and there are 135 different types in the world collection, he said.

The first lunar meteorite was recovered in the Antarctic by the ANSMET program.

Rocks from Mars also have been discovered there.

"The beauty of the Antarctic is not only is it a huge collection area, but with the movement of the ice, as soon as meteorites fall, they're in a deep freeze," Keil said.

Thus, they are preserved to stimulate new planetary science research and understanding of the solar system, he said.

http://www.kaleo.org