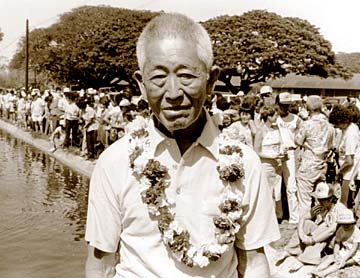

Soichi Sakamoto

Swimming coach

By Ben Henry

‘ahead of his time’

Special to the Star-BulletinSOICHI Sakamoto always will be remembered for the countless swimming champions and Olympians he inspired.

But those who knew him say it's what he did for those who weren't champions that made him special.

"He was a mentor to many young people," said Wally Nakamoto of Manoa, a diving coach of 42 years and former Sakamoto protege. "He left behind a legacy that I followed for the years I coached. He was a man of great integrity."

Nakamoto, who coached diving at the University of Hawaii for 30 years, cannot even begin to quantify the number of Olympians Sakamoto inspired. But he said it was the little victories -- a wayward youth directed, a wandering mind focused -- that thrilled Sakamoto most.

"He tried to instill in the next generation that it's about giving back to the sport what the sport gave to me," Nakamoto said.

Sakamoto, who coached at UH from 1945-61, is still well-known in swimming circles.

"He was one of the greatest coaches of all time," said Sam Freas, current University of Hawaii swimming coach and president of the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

"He used swimming as a way to basically show people that, through hard work, a lot of great things can happen," Freas continued. "He got them to think bigger than just the island perspective, and was very innovative."

His innovation was one of the things that set him apart.

"I remember he used to watch the fish swim at the aquarium, and he got the idea of how they cut through the water," Nakamoto recalled. "He used the goodness of what the creatures did and tried to put that into practice."

Sakamoto utilized the current in irrigation ditches on Maui sugar cane fields, where he started his swimming career, to train swimmers. Freas said it's a technique only recently duplicated by modern technology.

"(It was) an early flume and he had them swim against the current," Freas said of Sakamoto, who died two years ago at the age of 91. "He was way ahead of his time."

Thalia Massie

The Massie Case

By Richard Borreca

brought turmoil

Star-BulletinIT started with a bored, flighty Navy wife's walk on a dark Waikiki night, and ended at Iolani Palace in the noon glare of racial distrust and worldwide publicity.

On the night of Sept. 12, 1931, Thalia Massie left a Waikiki dance. She said she was kidnapped, beaten and raped by as many as seven men. It became known as the Massie Case, stirring such bitter feelings of racism and violence that Hawaii was nearly taken over by the military.

When police produced five men who had been pulled over for a separate offense, they were charged with the crime. In court, Massie identified four of the men as her attackers. But the defense hammered away at the credibility of witnesses who said they saw Massie walking from the party. The jury was deadlocked, and after 97 ballots over 100 hours, it was dismissed.

The city went into uproar. Sailors brawled and rioted in the streets, and Adm. George Pettingill telegraphed to Washington that "Honolulu was not a safe place" for women and Navy wives. One defendant was abducted and beaten. Then on Jan. 8, 1932, defendant Joseph Kahahawai was kidnapped while leaving court and murdered.

Police, stopping a suspicious car speeding near the Blow Hole, found Kahahawai's body in the trunk. The driver was Thalia's mother, Grace Fortescue. Passengers were Lt. Thomas Massie, Thalia's husband, and E.J. Lord, an enlisted man under Massie's command.

All three were charged with murder. A fourth sailor was charged the next day, and across the mainland, newspapers picked up the sensational case, claiming it was an instance of honor avenged.

The four were convicted of manslaughter in a trial that featured famed attorney Clarence Darrow for the defense. But their sentences were commuted to one hour.

The Massies divorced shortly thereafter. Thalia committed suicide in 1963 after two earlier, unsuccessful attempts. Thomas Massie disappeared after leaving the Navy.

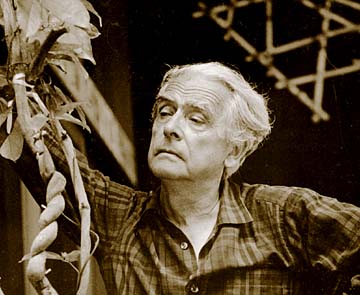

Jean Charlot

Paris-born artist

By Cynthia Oi

embraced the islands

Star-BulletinJEAN Charlot once said he came to Hawaii because he thought it was near Haiti.

In an interview for "Artists of Hawaii," Charlot told of an encounter with Ben Norris, then chair of the University of Hawaii's Art Department.

"He was looking for somebody he could induce to come and teach art in Hawaii," Charlot remembered. But the artist had just received an invitation to go to Haiti.

"I had a canny idea that perhaps I could go to Hawaii ... then I could go to Haiti on the weekends."

When he learned the two were very far apart, he chose Hawaii "for no other reason except that Ben was a nice guy."

The decision was a turning point for the artist as well as for the islands. The Paris-born Charlot arrived here in 1949.

He embraced the island's lifestyle and its people, said artist John Wisnosky, who filled Charlot's UH position when Charlot retired in 1966.

"He really loved Hawaiian people and his subjects for the most part were drawn from Hawaiians," Wisnosky said. "He learned the Hawaiian language and wrote poetry in Hawaiian." Charlot also wrote three plays in Hawaiian.

His works were hugely popular and his creations graced public places -- UH's Bachman Hall, Leeward Community College Theatre, the United Public Workers building on School Street -- making his art accessible.

"That's why he was so genuinely liked by the community," Wisnosky said. "They could understand his art -- people at work, people at play, people with children, people in happy situations."

Charlot continued his art until his death in 1979. He also worked in oil and sculpting and illustrated books. He was a teacher and a Star-Bulletin art columnist, and wrote books on art criticism and Mexican architecture.

"Charlot has to rank as among the most historic of the visual artists who have lived in the state," Wisnosky said.