Chuck Gee

He was the dean of

By Russ Lynch

tourism at UH

Star-BulletinCHUCK Gee found a way to shelter from what he calls the money-short "starvation climate" at the University of Hawaii. He persuaded others, mostly businesses in the tourist industry, to pay some of the costs of housing and running the UH School of Travel Industry Management.

"Your survival depends on your ability to bring in resources," said Gee, in an interview just before his September retirement as TIM dean.

That was one of the differences Gee brought when he took over TIM in 1976, after eight years as assistant dean. When TIM was started under Edward M. Barnet's leadership in 1967, there were those who wanted it to be purely a hotel school. Like Barnet, who was forced out at the then-mandatory retirement age of 65, Gee worked to broaden TIM to cover all aspects of the tourist industry.

"In that, I think we have done a remarkable job because we've had the support of the industry," Gee said.

He has been a forceful public advocate for tourism, often warning of the industry's fragile nature and the danger of collapse if tourism infrastructure and the aloha spirit aren't maintained.

Gee was born and raised in San Francisco, got a bachelor's degree at the University of Denver and a master's at Michigan State. He managed a guest ranch for a couple of summers and was director of food service at the University of Denver when he began teaching, as assistant professor and associate director of the private university's School of Hotel Administration from 1960 to 1967.

He became a visiting associate professor at the UH College of Tropical Agriculture in 1967 and, in 1968, associate dean and professor at TIM. Now he plans to do some consulting work.

Barnet went on to start a competing travel industry management school at what is now Hawaii Pacific University. He died in 1983 at age 81, and is remembered as a travel industry education pioneer.

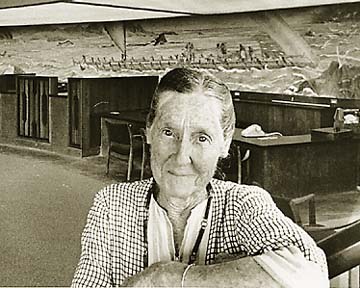

Juliette May Fraser

Beloved artist had

By Cynthia Oi

‘glint in her eye’

Star-BulletinONE day, Pam Barton saw her friend Juliette May Fraser sitting at a bus stop in front of the Honolulu Academy of Arts. Buses zoomed by, but the artist remained seated, staring at the sidewalk.

"I said, 'Oh, May, did you miss any buses?' And she said, 'Yes, two.' But she kept looking down at the sidewalk," Barton recalled.

Fraser was watching two lines of ants crawling toward each other from different directions, touching each other occasionally as they worked.

"That was what was amusing her. She said she wished she knew where they were going. So we sat there together and watched the ants."

The anecdote illustrates a mind that wondered about possibilities, that could find value in things incidental to others.

Juliette May Fraser was born in 1887 in Honolulu. After graduating from Wellesley College in Massachusetts, she worked as an educator, like her mother and father who came to the islands to teach.

"That was practically the only thing a woman could do then," she told an interviewer a few years before her death in 1983.

But her heart since childhood had been captured by art, so she saved her salary to study at the Art Students League in New York.

She returned to Honolulu, teaching for a few more years before receiving a commission to paint a mural for Mrs. Charles Adams, grandmother of Ben Dillingham. That started her on a lifelong path of painting murals, from the World's Fair in San Francisco to Ipapandi Chapel on Chios Island, Greece, where her work was so beloved that the chapel's street was named after her.

Fraser's work wasn't flashy. In fact, critics described her art as "deceptively simple." And the tiny, unassuming woman usually dressed in a palaka shirt and slacks she sewed herself.

"She was truly a lady," said Barton. "And she always had a mischievous glint in her eyes."

Charles W. Dickey

Architect’s work in

By Harold Morse

Hawaii notable

Star-BulletinNO one man has a more central place in Hawaii architecture than Charles W. Dickey.

Born of a kamaaina family in 1871, he grew up on Maui, graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and practiced architecture in Honolulu from 1895 to 1904, then some years in Oakland, Calif., and again in Hawaii from the early 1920s until his death in 1942 at age 70.

He designed Farrington High School, buildings at the Kamehameha Schools, Waikiki Theatre, Varsity Theater, Halekulani Hotel, Naniloa Hotel in Hilo, the old Kona Inn and a number of commercial buildings here.

Dickey also designed numerous structures at Pearl Harbor. Other landmarks with Dickey blueprints are Montague Hall at Punahou School, Wilcox Hospital on Kauai, Queen's Hospital, Children's Chapel of St. Andrew's Cathedral, an addition to the Library of Hawaii, Maui County Library and a number of fine homes in the islands.

He also assisted, with other architects, in designing Honolulu's City Hall.

Many fine edifices produced in Dickey's later Hawaii career established his reputation as the leading island architect. Dickey summed up his work on the U.S. Immigration Station in the 1930s with: "In general the buildings consist of low-lying masses of cream-colored stucco walls surmounted by graceful sloping roofs of variegated green and russet tiles."

He referred to "a touch of Chinese architecture" at the entrance, adding, "This portico is the most important architectural feature of the group."

Dickey designed high hipped roofs with wide overhanging eaves for the group of cottages at the Halekulani Hotel beginning in 1926.

Referring to Hawaiian grass houses as his inspiration, Dickey said, "I believe that I have achieved a distinctive Hawaiian type of architecture."