LIFELINE

A Campbell High School teacher

Class needs contributions

who is battling cancer is showing

at-risk students the light in a

program called Kulia I Ka PonoBy Crystal Kua

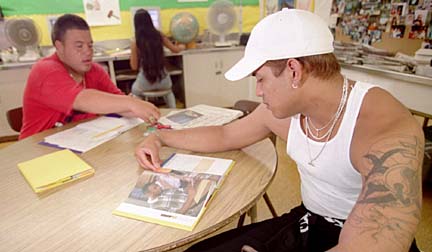

Star-BulletinTattooed, big and mean, Pete Siu Sauilimau had run with a Crips gang in Compton, Calif., and been jailed in a juvenile detention center.

When he walked into Lani Ramos-Harrington's class at Campbell High School last year, he brought trouble with him.

"His very first words to me, 'F--- you, I not going do any work,' " Ramos-Harrington recalled.

He would learn, though, that Ramos-Harrington was a lifeline for troubled youths like him, reaching out to them even as she was coming to terms with her own tribulations.

Gang colors, profanity and attitudes are checked at the door in Ramos-Harrington's class, Kulia I Ka Pono, which means "striving toward excellence."

Students not only learn academic subjects but also life, job and computer skills. The Kulia I Ka Pono program was designed to help at-risk students, kids deemed destined for failure.

Kaleo Thomas was also in the class. Each day he caught the bus from Hauula to attend the Ewa Beach high school, his sights set on graduating and trying to avoid repeat incarceration at the Hawaii Youth Correctional Facility.

"I was no good. I was a punk and troublemaker," said Thomas, who at the time was a member of a Bloods gang, mortal enemies of the Crips. "If you had what I wanted, I take 'em," Thomas said.Sauilimau's family had sent him back to Hawaii to get him away from trouble. Now he was in class every day with a rival gang member, and Campbell faculty and staff braced for the worst.

But while the students had their share of problems, the violence that officials feared never happened.

Instead, in a class seen as the last stop for the seemingly hopeless, school officials found emerging young adults who shared sodas, camaraderie and a desire to change.

An abnormal pap smear in 1997 led to a diagnosis of cervical cancer for Ramos-Harrington.

It's a subject she doesn't like to talk about. She wants the focus to be on her students.

Ramos-Harrington was out for about a month last school year undergoing treatment in California. Her goal was to get back to the classroom as quickly as possible.

With Ramos-Harrington's absence came concern from her students about her condition and their future.

"We was shocked cause we neva know how was going be if she wasn't there," Thomas said.

Some students said they probably wouldn't have returned if Ramos-Harrington hadn't come back.

Returning to school was a challenge for her. Some days she was so weak she couldn't get out of bed.

On days she went to class, she sometimes re-examined her reasons for being there.

"I would sit here with my tea and with my own doubts and wonder, is it worth it?" she said. "And, you know what, it was."

The cancer is in remission now, she said.

"I'm feeling well," she said. "I think I'm getting more sassy."

It looks like a home economics classroom with kitchen and dining area, but it's actually home to Kulia I Ka Pono.

Sometimes students would cook breakfast, sit around the table, eat together and talk.

Campbell officials started the program when they saw an increase in the number of students with emotional problems and volatile backgrounds -- arrest records, dysfunctional families, high truancy and drug use.

"They had needs that go beyond the school's capabilities," Principal Louis Vierra said.

"(Vierra's) looking at the statistics and saying, 'What are we going to do with these kids?' " Ramos-Harrington said.

The 39-year-old special education teacher was given a semester to develop a program curriculum, and in February of last year, Kulia I Ka Pono was born.

Out of the 12 students in her first batch, nine graduated with certificates of completion, she said.

They included Thomas and Sauilimau.

Thomas, straight out of the youth facility when he started the class, didn't want to sit on a chair because it was blue -- a rival gang color, she said.

Sauilimau had no qualms about walking up to other kids at a bus stop and "jacking" them for money.

But while they would go to their separate turfs outside class, Sauilimau and Thomas became kindred spirits and best friends inside of class.

"The gangs and stuff were put aside," Thomas said. "It's like we knew each other."

And they changed their perception of school, graduating last school year.

"It helped me learn. It was fun. We got to respect each other," said Sauilimau, 19.

"I learned to read, write, do math that I never knew how to do before," said Thomas, also 19.

Not all the students in the program have criminal pasts. Some just needed the right kind of environment to blossom academically.

Crystal Manalo, 16, is an articulate, inquisitive senior who fell behind in regular classrooms.

"I have a hard time working in a big group," she said. "I wouldn't understand when they'd go too fast. ... (The teacher) didn't explain what I needed to know."

But to be labeled "special education" at such an awkward age is tough.

In Kulia I Ka Pono, Manalo learned coping skills. She improved her speaking abilities and learned to ask more questions.

"I can ask for help better and I can understand better," she said. "People think it's a regular class."

Seventeen-year-old Mitchell Montayre is a freshman because he didn't go to school after eighth grade.

"I run away from home," Montayre said. "I was like cruising the streets for two years."

He attended school for the first time in years earlier this month, landing in Ramos-Harrington's class.

"No mo' too much kids," Montayre said. "But still get all the subjects everyone else get."

Montayre said he wants to graduate some day and maybe become a certified mechanic.

Students and officials attribute the program's success to Ramos-Harrington.

"She go out of her way and do things for the class," Thomas said.

"You've got to have the right person in the right place," Principal Vierra said. "She goes beyond being a teacher."

Ramos-Harrington said one of the most important lessons she's tried to teach her students is to give back to the community. She took them to Makakilo to tutor elementary kids, a project the students enjoyed.

"They want but they don't know how to give back. But once we started, they get big heart," she said.

Sauilimau knows what the class did for him. "I'm alive," he said. "This class helped me to survive."

While the Kulia I Ka Pono class is long on heart, it's short on resources. Class needs contributions

Teacher Lani Ramos-Harrington said students can't afford to pay for class dues, cap and gown and a yearbook, so they have to raise funds. This year they are seeking contributions but also need more powerful computers to connect to the Internet.

Anyone interested in helping can call Campbell's Kulia I Ka Pono program at 689-1245.

Crystal Kua, Star-Bulletin