By Betty Shimabukuro

Star-BulletinIF it's not the thrips it's the rain, if it's not the rain it's the wind, if it's not the wind it's the declining U.S. military presence in the islands.

With all the pitfalls waiting to sabotage a farmer, it's cause for celebration when one of them makes a success of this very risky life. Because it's never a sure thing. And because it can take decades.

"Once a farmer I don't think you want to give it up," says Douglas Duarte, a Kona coffee farmer and president of the Hawaii Farm Bureau Federation. "Being outdoors, doing what you want ... when you meet the challenge it feels good."

And so next week they will celebrate. At Roy Yamaguchi's restaurant, with a gala dinner, "May the Source Be with You." A superstar team of chefs will serve up plates of food, assisted by culinary students and working with produce from island growers. All to fund scholarships for another generation of chefs and farmers.

MAY THE SOURCE BE WITH YOU

Hawaii Farm Bureau Federation Benefit

Featuring: Foods by chefs Roy Yamaguchi, Alan Wong, Hiroshi Fukui (L'Uraku), D.K. Kodama (Sansei Seafood Restaurant and Sushi Bar) and Wayne Hirabayashi (Kahala Mandarin Oriental hotel)

Dinnertime: 6-9 p.m. Monday

Place: Roy's Restaurant, Hawaii Kai

Admission: $75, to benefit the farm bureau's scholarship fund

Call: 848-2074

It's the working partnership of farm and restaurant that has become the circle of support for many small farmers today.

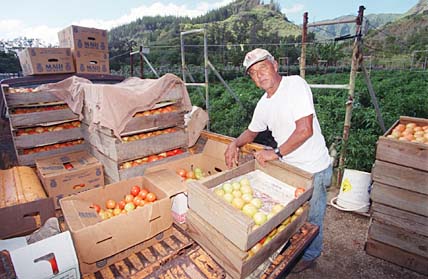

Graf Shintaku has been growing tomatoes in Hauula since 1955. He was in his mid-20s when he purchased the 2.5-acre hydroponic farm and in that time he has weathered many a mild success and many a near disaster.

On the high side: A growing interest on the part of the military after the Korean War in hydroponically grown produce. For many years military outlets bought out nearly all of Shintaku's crop.

On the low side: The tomato spotted wilt virus, borne by a bug called a thrip, "it just about wiped us out -- we had to get out of tomatoes," Shintaku says.

He battled the virus for a few years before finally giving in to the advice of experts and clearing out all his plants for six months. Now, every January, he goes out of the tomato business for three months. "We clean out everything. Not one tomato plant in the whole place."

In the interim he grows kai choi, or mustard cabbage, which doesn't harbor the thrip and which thrives in the winter months.

The evil thrip now defeated, or at least kept at bay, the Shintaku farm is thriving. Yes, Hawaii's military presence is on the decline and that means those sales are down. But the vine-ripened Hauula tomato has become a favorite of island chefs, and that means Shintaku can now sell everything he grows."We knew that was probably the way to go, with all these chefs really pushing the local produce."

Today's high side: The average plant produces 15 pounds of tomatoes in a six- to- eight-month growing season, for a total of 337,500 pounds each year. He sells the tomatoes for $1 to $1.25 a pound.

With today's better tomato varieties, as well as improvements in insect control and the nutrient mix for the hydroponic system, yields are way up, Shintaku says. In the '50s, "if I could get 5 pounds per plant, that was good."

Through all his ups and downs, Shintaku has been a loyal member of the farm bureau. He credits the group for giving farmers an education in such topics as bug control, back in the days when he was starting out. "That was the only thing farmers really had ... the only way to get information like that was through the farm bureau, going to meetings."

It was simple, low-cost and low-key. Today's mission is far more complex -- and political.

The farm bureau has become the primary advocate for farmers at the Legislature, an active lobbying group with a $300,000 budget and a full-time staff.

Membership includes industries from livestock to aquaculture, tropical fruits to coffee and macadamia nuts, even beekeeping.

"We're growing and we want people to know who we are," farm bureau president Duarte says.

At its annual convention Oct. 21-23, delegates will identify issues to take before the state Legislature next session. Duarte expects the focus to be land and water issues, particularly a pending land assessment that would evaluate all of the state's open spaces, determining which are best for agriculture and which are marginal and best left to urbanization.

"This whole approach is to have a plan in place to protect good ag lands from being developed," Duarte says.

More scary stuff on the farmer's horizon: Certification, where large retail food buyers require proof that a farm is delivering produce free of the type of contaminants that have caused food scares on the mainland.

It's the sort of practice with the best of intentions, but Dean Okimoto of Nalo Farms in Waimanalo warns that the expense of compliance could do in many a small farm. "For the guys that are struggling now, forget it, they're gone."

Certification means private inspections of farms to make sure their food-handling practices meet certain standards, and it means processing plants to remove bacteria from produce, probably through chemical treatments, Okimoto says.

"There's no sense in moaning about it anymore. You can have 10 million reasons why we don't need it, but there's no sense even trying to fight it anymore."

It may never become law, but in order to continue selling to large retailers, he says, most farmers will have to comply.California growers are up to speed, he says, but Hawaii farmers aren't even sure of the rules. At his own farm, he estimates compliance will cost $500,000 to $1 million -- not costs he can pass on and stay competitive.

He looks toward the farm bureau and the state to help the small farmer meet certification standards -- through, for example, cooperative processing plants.

Another threat to the risky profession of farming, but because this is a story about successes, Duarte gets the last word.

Despite all these challenges, he says, it's a healthy industry, fueled by opportunity and a new, savvy, cooperative spirit among farmers.

The farm bureau will deal with certification as well as other problems, such as dwindling state dollars for farm-assistance programs, he says. Farmers are proactive now, willing to share costs and help themselves. "Agriculture is not there just to hold out our hand and say, "Give me.' "

Click for online

calendars and events.