Christmas 1941

in Hawaii was not

a time to rejoice

Martial law was in effect,

By Richard Borreca

Army and Navy dependents

were evacuated and some

local Japanese were incarcerated

Star-BulletinChristmas in Hawaii, 1941. The Christmas lights strung along Nuuanu Avenue, one of the main shopping districts, have all been torn down or turned off. The new bikes, wagons and dolls that would have been Christmas presents were still sitting on docks in San Francisco, shoved aside as the weapons and supplies of war were shipped to Honolulu.

In San Francisco, the first shipload of evacuees from Hawaii landed on Christmas Day. Some of the women were new widows, others didn't know what happened to their husbands. Each morning on the ship, they rolled bandages and dressings for the gravely wounded from Pearl Harbor who were aboard.

For most on Oahu, Christmas was a military-ordered work day. It was a time of deep worry and fear. No one wanted to be the target of another Japanese attack."Men who in the normal course of their lives would be at home sharing the yule spirit of gladness, were working tirelessly for victory or preparing to secure it with their lives," the Honolulu Star-Bulletin said in a front-page Christmas Day commentary.

First at Nuuanu Cemetery and then at other sites, the military buried more than 2,500 young men killed in Japan's Dec. 7, 1941, surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

Local gardens gave up their red poinsettias and hibiscus for small bouquets on each grave.Even as they grieved, civilians feared another invasion by Japan; indeed, enemy submarines were sporadically shelling island ports and harbors. Within a month of the attack, 20,000 Army and Navy dependents and 10,000 island women and children left Hawaii, fearing for their safety.

The Matson freighter Lahaina was set ablaze by a submarine on Dec. 11, and its lifeboat did not reach Maui until Dec. 21. Another Matson freighter, the Manini, had been sunk by a torpedo.

By Christmas, all islanders over age 6 were being fingerprinted. As early as 1:30 p.m. Dec. 7 -- a mere 5-1/2 hours after the attack -- printing presses had begun churning out military-issued civilian ID cards. It was a contingency the U.S. military had planned but feared: The cards were to be used to identify dead in case of another attack.

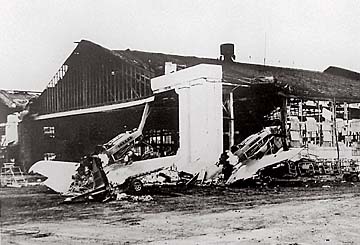

Repairs begin at Pearl Harbor

At Pearl Harbor, a massive salvage operation was under way. The first order was to free sailors trapped in capsized ships. With divers guided by men tapping on the ship's hulls, the last man was rescued Dec. 9, two days after the bombing.Damaged ships with functioning weapons were stripped or repaired. The Pearl Harbor dry docks ran around the clock, working so fast that two cruisers -- the Honolulu and the Helena -- were back at sea and steaming for larger repair yards in California by the first week in January.

On land, in less than a week, the Army extended the Bellows Field runway from 2,200 to 4,900 feet-long enough for the largest bomber of the day to land.The military's speed was not limited to construction and repair; it also swiftly moved to control Hawaii's civilian population. Territorial Gov. Joseph Poindextersurrendered Hawaii to the military after talking to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

John Burns, a police captain in charge of the espionage bureau at the time of the attack and later Hawaii's governor, once recalled that a sobbing Poindexter called Robert Shivers, the FBI agent in charge, asking for help to preserve the Territory's own form of law.

"That was amazing to me a little bit that the guy who was governor was crying and asking Shivers whether he should go along with the Army . . . he didn't particularly want to do it," Burns said later.

The military powers meant the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights were no longer in effect in Hawaii: The military handed down all the laws.

Loyalty questions fuel martial law

Much of the reason for martial law was the military's fear that Japanese citizens and Americans of Japanese ancestry would help the enemy.Just days before Christmas, farmers next to West Loch were ordered to leave their farms by sundown. The order was later modified to give them two days.

Move from Iwilei, the Japanese were told, or be shot by the military police. About 1,441 local Japanese were eventually interned: they were first sent to a hastily created detention center at Sand Island, where they were called prisoners of war.

After the war, with censorship lifted, federal magistrate Judge J. Frank McLaughlin, condemned the military's action.

"Gov. Poindexter declared lawfully martial law but the Army went beyond the governor and set up that which was lawful only in conquered enemy territory namely, military government which is not bound by the Constitution. And they ... threw the Constitution into the discard and set up a military dictatorship."

Both military commanders at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, Lt. Gen. Walter Short and Adm. James Kimmel, had been relieved of duty. Washington officials blamed the two for not being prepared for the attack, but later documentation showed that possible warnings of a Japanese attack were stuck in Washington, D.C., and never sent to Kimmel and Short.

But military preparation did not cover everything. In the darkness of the morning after the attack, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers roared onto Punahou Schools' campus and seized it for a military camp. Debate at the time swirled that the Army actually was targeting the University of Hawaii, but turned one block early, winding up at Punahou.

At 5 a.m. Dec. 8, Punahou president Oscar Shepard recounted, "The director of the cafeteria and dining room was called by the Army and ordered to provide breakfast for 750 men and was told that the facilities were being taken over, including school supplies."

The campaign to retake the Pacific from Japan was fought in a series of battle that cost thousands of American and Japanese lives. High price of war

While it is impossible to calculate the exact number of Japanese lives lost on ships and in some island battles, these figures are from U.S. military historians.

Pearl Harbor:

American deaths: 2,403

Japanese deaths: 55

Iwo Jima:

American deaths: 6,500

Japanese deaths: 21,000

Guadalcanal:

American deaths: 1,600

Japanese deaths: 24,000

Okinawa:

American deaths: 7,613

Japanese deaths: 110,000

Hiroshima:

Japanese deaths: 71,000 (immediate)

Nagasaki:

Japanese deaths: 38,000 (immediate)

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin is counting down to year 2000 with this special series. Each month through December, we'll chronicle important eras in Hawaii's history, featuring a timeline of that particular period. Next month's installment: October 18. About this Series

Series Archive

Project Editor: Lucy Young-Oda

Graphics by Bryant Fukutomi and Lucy Young-Oda