Lifelong quest for gender: Powerful drugs

have brought LiAnne Taft's body closer to her

defined identity; at issue is whether society

should look beyond the process and

accept sex changes

Transformation

Some people are cruel,

others merely curiousState law not definitive

By Christine Donnelly

Source of gender?

Paddlers' opinions mixed

Insight On Internet

Star-BulletinLooking into the eyes of LiAnne Taft, one sees an open, self-confident woman. But it wasn't always so. For most of her life, Taft secretly struggled to define her very essence. Was she male? Female? Neither? Both?

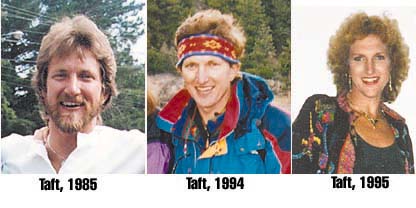

It took lonely, shame-filled years for Taft to accept that although her body was male, her mind was not. Four years ago, Taft began living as a woman, and transforming her body with powerful drugs that promote female characteristics and suppress male ones. Medically, she's a "pre-operative transsexual woman."

Now at the center of a sex discrimination complaint against the Hawaiian Canoe Racing Association, Taft hopes critics might come to see her paddling as a woman not as a ploy to win races, but as an essential expression of her true self.

"Please let me live my life," said Taft, 46. "Not only am I woman, I'm a human being. We're all human beings."

To understand the evolution of William E. Taft into Li Wai'oli "LiAnne" Taft, it helps to start at the beginning.

Some of the earliest memories are of torment and confusion. Of sneaking into mom's closet to try on shoes, of poring over fashion magazines the minute everybody else left the room, of recoiling in horror when told to "stand up like a man" to the neighborhood bully.

Growing up in Rhode Island in the 1950s, Taft was desperate to know "why my body, mind and soul were so disconnected." But terrified that even asking would drive family away, young Bill said nothing. He swung from depression to anxiety to angry outbursts.

One day, around age 11, Bill just blurted out to his parents: "I like to wear mom's shoes." He was taken to a psychiatrist who talked only to the mother and father. "I stayed in the lobby," Taft recalls now. "When it was over, (the doctor) came out and said 'Don't worry, Billy, you'll grow out of it.' From then on, it was just bury it, bury it, bury it. But I couldn't."

Alone in the basement at home, the teen-age Bill wore his mother's and sister's clothes, culled from a storage chest. One day, a pair of high heels hidden in his room disappeared. But whoever found them never mentioned it.

Bill coped best by "always staying busy, focused on something else," such as earning bachelor's and master's degrees from the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and embarking on a career in recreation management. Friends from that time remember Bill as an outgoing, highly energetic man with a taste for colorful clothing and adventurous sports.All his life, Bill had favored female friends. In 1988, he married a friend he'd grown to love, and who was unaware of his quandary. But if he'd hoped the union would anchor him more firmly in the male world, the opposite occurred.

"I just couldn't stop thinking about being a woman," Taft says now, recalling how the cross-dressing escalated. "The fear of discovery just intensified. I loved my spouse deeply and I didn't want to let her down."

In 1993, the couple moved to Hawaii, with Bill working as a children's program director at the YMCA's Camp Erdman on Oahu's North Shore. But his anxiety grew and he was increasingly unable to concentrate.

Then, in September 1994, Bill's father died. That was the turning point.

"Here was someone who had loved me my whole life, and who I had loved, and I realized he never even knew the real me," Taft says. The heartbreak was compounded because "he had been reaching out to me ... I had not responded to that love out of fear of rejection."

Bill entered the YMCA's Employee Assistance Program and revealed his situation -- known as "gender dysphoria" -- for the first time. The next month, he was laid off. YMCA executive director Don Anderson said Taft was one of about a dozen people laid off at that time due to budget cuts. "It was strictly fiscal ... " Anderson said.

One by one, Bill began taking the complicated medical, legal and emotional steps that would remake him as LiAnne.

"April 23, 1995, is what I consider my rebirth date," says Taft. "I gave up a lot. I had friends, a marriage, a spouse and family that loved and accepted me. But I was not Bill, not the person they thought I was. I cannot put into words the torment of that."

The transformation was marked by exhilaration and relief, but also deep sorrow as dumbfounded family and friends learned the truth. Most tried to be encouraging, but some considered the quest morally wrong.

Taft was divorced in 1996; there were no children. Taft has sporadic contact with her older brother and sister. She talks to her mom on the phone every week, but they have not met in person since the switch. "She tells me she loves me. I'm her child. Yes, she knew me 42 years as Bill, as her son. But she's trying to understand me as a daughter."

A lesbian, Taft says she has had no serious relationships since the change.

Taft works for a small floral supply company and in June was elected to the Makiki Neighborhood Board. She knows she never will lose all masculine traits. The broad shoulders, large hands and Adam's apple throw people off. A few people are cruel, call her a freak. But most seem merely curious. So whenever she can, Taft makes eye contact.

"I smile. It's disarming. I know I present a confusing picture," she says. "But once I get to know people, they tell me they see the soul of a woman. That's what I've always seen. So how can I ever regret freeing myself?"

State law not definitive on gender

By Christine Donnelly

Star-BulletinHawaii law does not explicitly define gender, making the case of the transsexual paddler more complex than most people assume, lawyers say.

The investigation of LiAnne W. Taft's sex discrimination complaint hinges on two questions: Can Taft, a pre-operative male-to-female transsexual, legally be considered a woman? And should the Hawaiian Canoe Racing Association, a private group, be subject to state anti-discrimination laws?

"I don't know that we've ever had a case in Hawaii exactly construing these issues," said lawyer Kirk Cashmere, a former legal director of the local American Civil Liberties Union who still handles civil rights cases.

First, determining gender: Taft's advocates say gender comes as much from the brain as the genitalia. But the HCRA wants to rely on birth certificates, which go by the latter.

"We've got to draw the line somewhere," said Michael Tongg, president of the HCRA and himself a lawyer.

Taft considers herself a woman, lives as one and for more than four years has taken female hormones that develop feminine characteristics, including breasts, and an anti-androgen that blocks the male hormone testosterone. Hormonally, she's "more female than most females," said Milton Diamond, a University of Hawaii specialist on the subject who knows Taft.

The drugs shrink the penis and testicles and cause impotence, sterility and loss of sex drive. But the genitalia, although impaired, has not been surgically altered, Taft said. Her DNA, or genetic code, remains as at birth.

The hormone therapy feminizes the body by redistributing fat to the hips and buttocks and reducing upper body strength. But it doesn't narrow the shoulders or waist, according to the Physician's Guide to Transgendered Medicine.

As for self-identity, Taft changed her name and numerous legal documents, including her Hawaii driver's license, to reflect womanhood. But she cannot change her birth certificate, which was issued in Rhode Island, without having sex reassignment surgery.

Without the birth certificate, Taft risks having her crew disqualified if she paddles as a woman in HCRA-sanctioned regattas. After years of accepting a driver's license to verify gender, the association in December 1998 passed a rule requiring birth certificates. The rule came amid complaints that Taft has an unfair advantage over other women competitors. She responded by filing a sex discrimination complaint with the Hawaii Civil Rights Commission.

Taft said she wants the surgery but can't afford the $15,000 cost, which is not covered by insurance. In the meantime, she carries a doctor's letter stating she "should be regarded and identified in all ways as a female."

But if the medical community has become less fixed on genital surgery as a prerequisite to sex changes, the courts have been slow to follow.

More than 40 states, including Hawaii, reissue or amend birth certificates, but after sex-change surgery, according to the handbook Legal Aspects of Transsexualism. For males-to-females, that commonly means removing the scrotum and redoing the penis into a vagina.

Cashmere and Hazel Beh, an assistant professor at the University of Hawaii who has written about the subject, said that on the mainland, federal courts have tended to rule against expanding rights for transsexuals, even sometimes assigning pre-operative transsexual women inmates to male prisons. State courts have tended to rule more liberally, they said; but neither could recall a recent case here or elsewhere just like Taft's.

Bill Hoshijo, executive director of the Hawaii Civil Rights Commission, declined to discuss Taft's case specifically. But he confirmed that Hawaii had no established legal standard defining sex and gender.

If the commission decides Taft is a woman, it moves on to the second question: Should the Hawaiian Canoe Racing Association, a private group, be held to the state law prohibiting sex discrimination in "public accommodations"? That investigation likely would focus on HCRA's membership, and how and where new paddlers are recruited, said Cashmere.

"For example, do they have a real exclusive screening process or is it a more open membership available to the general public?" said Cashmere. The fewer hurdles there are to join, the more likely that the law applies.

A comparable case could be lawsuits filed against the Boy Scouts of America, which refused to employ homosexuals. Although the Boy Scouts is a private group, plaintiffs claimed it was subject to anti-discrimination laws because it recruited members at public schools. The New Jersey Supreme Court and a Chicago Circuit Court both recently ruled against the Boy Scouts.

Tongg said his group is not discriminating but "trying to keep competition fair. It's really sad it's come down to this. I've said all along that I consider this a lose-lose situation."

Source of gender:

By Christine Donnelly

Brain or body?

Star-BulletinNo one has proved what causes transsexualism, with medical researchers and social scientists considering everything from inborn genetic traits to psychological factors.

Earlier this century, gender identity disorders were primarily considered mental illnesses. But scientific findings in the past few years suggest gender is dictated by the brain, rather than the genitalia or hormones.

Even researchers focusing on disparate causes agree that transsexualism usually manifests itself in childhood, according to a handbook published by the International Foundation for Gender Education.

A multipronged approach helps transsexuals reconcile the profound disconnect between their brains and their bodies. The usual treatment for male-to-female transsexuals includes psychological counseling, resocializing as a woman -- known as the "real-life test" -- establishing a new legal identity, hormone treatments and sometimes genital reconstructive surgery.

Various medical sources estimate that from 1 in 10,000 people to 1 in 50,000 worldwide are transsexual.

No agency tracks the population in Hawaii, but applying that rate would make it from 24 to 120 people. Advocates say that sounds too low, but have no precise number.

Some religions, including the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, condemn sex-change surgery and recommend counseling alone to try to overcome gender confusion.

Transsexuals are not the same as transvestites, more politely known as cross-dressers. Transsexuals cross-dress to help foster their need to be the opposite sex.

Transvestites enjoy wearing opposite-sex clothes but do not want to physically change genders.

Paddlers’ opinions mixed

By Christine Donnelly

Star-BulletinWhile anyone can see that she is a strong, muscular person, fellow paddlers disagree over whether a transsexual athlete has an edge in a team sport that also depends on agility and timing.

LiAnne W. Taft "isn't really unique in her height or strength. I think we need to credit everyone in the boat," said Julia Morgan, a novice paddler in the Koa Kai Canoe Club. Taft belongs to the club, although not the same crew.

But a paddling coach who refused to be named said when women competing against Taft "look over and see a man, in their minds they've lost the race."

In the season just ended, Taft -- as part of a six-person crew -- was in 10 races and won four. She did not paddle in the state championships. She came in second among Koa Kai women in solo timed sprints.

Koa Kai, for which Taft has paddled since 1996, is in the Na Ohana O Hui Waa paddling association, which does not require birth certificates. The stricter rule for confirming gender would have applied had Taft paddled at states, which is sanctioned by the Hawaiian Canoe Racing Association.

Hazel Beh, a University of Hawaii assistant law professor who wrote a letter for Taft outlining some legal issues, said the 1970s case of male-to-female transsexual Renee Richards should have settled the question of fair competition.

When the Women's Tennis Association tried to ban Richards, New York courts ruled against it, finding a "paucity of evidence" she had a competitive edge.

Richards, however, had had sex-change surgery. But Beh said the ruling was still relevant to Taft (who has not) because the courts did not find that strength was derived from genitalia.

The HCRA rule says a paddler whose gender is challenged must produce a birth certificate. And it leaves open the possibility that chromosome tests could be required even if a birth certificate is produced.

Taft calls it a mean-spirited attack on "a miniscule minority." In one letter of complaint, she estimated fewer than 20 transsexuals had ever paddled statewide. HCRA president Michael Tongg said he had "no idea" how many transsexuals compete now. Others estimated from one to four besides Taft.

Some people have suggested that Taft compete as a man, perhaps not realizing that could jeopardize her feminizing regimen. This includes not only taking female hormones and a testosterone blocker, but also adhering to medical standards that require transsexuals to live continuously in the new gender.

Mary Martin, a Honolulu lawyer and paddler who knows Taft, said focusing on sports trivializes her larger struggle. "She's not really affecting anybody. She's made a tougher decision than most of us will ever be faced with in our entire lives. It's not all about winning."

For more information, check out these Web sites: INSIGHT ON INTERNET

The Hawaii Civil Rights Commission: http://www.state.hi.us/hcrc

Treatment standards for transsexuals: http://www.tc.umn.edu/nlhome/m201/colem001/hbigda/hstndrd.htm

The International Foundation for Gender Education: http://www.ifge.org

Hawaii Transgendered Outreach: http://htgo.transgendered.org