Michael Kliks seems to have

The sweet life

lived many lives. He's been abducted

twice--once in Thailand and once in

Nigeria-- and was a Vietnam War

photographer. Now the Manoa

beekeeper is living...

Wednesday: A little honey in your food

By Cynthia Oi

Star-BulletinTAKE a ride with Michael Kliks and you'll get running commentary on Hawaiian geology, history, legends and folklore; on Manoa drivers; bodysurfing; the politics of agriculture; guinea worm disease; malaria; the civil rights and sovereignty movements; early childhood learning; parasites; photography and the Vietnam War; his daughters; Nigeria; Burkina Faso; Thailand; Mexico; the Oregon coast; Germany; Colombia; his truck; and bees.

All of this tumbles from his mouth as he deftly threads the candy-apple red vehicle from his house beneath the moist greenery of Waahila Ridge through narrow Manoa streets to the arid, kiawe-scrubbed slopes of Diamond Head.

Kliks is a master beekeeper, lending his buzzy charges out for pollination service, tending their hives and harvesting their sweet product for sale by his Manoa Honey Co. For most people, a life with stinging insects would be edgy enough. For Kliks, it is a calm respite compared to the rest of his life.Kliks, 57, holds a Ph.D. in medical parasitology and entomology. He knows his bugs and has been all over the world looking for ways to control the diseases and human suffering these creatures spawn. As a scientist, he has received three Fulbright commissions and numerous grants, consulted with stellar institutions and managed research and testing facilities.

He's been to places where bedbugs were common and clean water wasn't, where bullet-ridden bodies covered the landscape and a camera was his only weapon in covering a war.

During the '60s, he worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in New Orleans and took part in the Waiahole-Waikane conflict in the 1970s.

He has been abducted twice, once in Thailand by the soldiers of his fiancee's father, and again by government officials in Nigeria, who thought he was trying to foment a revolution.He lived up the road from convicted killer Charles Manson in Topanga Canyon. He worked with famed photographer Ansel Adams, and has had his work published in photo journals.

He is a serious bodysurfer, winning master's division championships. He hikes, fishes, swims, skis on snow and water and dives in the ocean and in water-logged caves.

For several years, he was a single father, raising his daughter while his then-wife studied for her Ph.D.

He speaks seven languages and midway through his life, is teaching himself Hawaiian.

In short, he's a character.

"I like to be connected," Kliks says, explaining his life of adventure. "There's plenty of things to waste your time. Drugs and politics are two of the main ones."

"I like to feel connected. And there's so much here in Hawaii that connects you."He has been linked to the islands for more than 20 years, moving here after his first wife, a virologist, came to the University of Hawaii. But of those years, he spent 12 overseas doing research projects.

"I've tended lots of other people's gardens," he says, chuckling at the metaphor. Now he's taking care of his own and they are all populated with honeybees.

When Kliks takes on a project, he does it fully. In his mind, keeping bees is no different from trying to eradicate guinea worm disease in Nigeria, which he has done.

He has thrown his whole being into beekeeping, using his training as a classic scientist for his framework.

At his home, he keeps hives that need special attention. The one there on a recent day was a swarm rescued from a house in Kaneohe by Craig Yano, a journeyman keeper who works with Kliks and who is also a bodysurfing buddy.

"Craig goes out a lot on the bee emergencies," Kliks says.Bee emergencies?

"When people find a large swarm or a wild hive, they call us and we go get them."

"People get very, very frightened," he says, but "there's little to fear from bees unless you're allergic."

The stings don't bother him. After climbing the ridge behind his house to examined a feral colony, he quietly tells his visitors, "I think it's best for us to go down now."

Retreating, he counts five stings on his arms, legs and face. "Well, I can't blame them. I got in their beeline. I needed a dose anyway," he says, explaining the venom seems to relieve his arthritis symptoms.

He rails against those who consider bees pests and spray them with insecticide. "Without bees, you won't get pollination in some crops and without that, you won't get any produce," he says.

Kliks sees bees as a way to increase the development of tropical and diversified agriculture in Hawaii.

"We import so much fruit from elsewhere -- mangoes from Mexico, for example. We should be growing that stuff here."

Pollination of crops grown in the islands is largely dependent on feral bees. If bees were hived in crop fields -- as Klik's bee management company, Island Pollination Services, does in Ewa and Maili -- quality and yields would improve, he says.Some supermarkets say the imports are cheaper, but Kliks questions the real costs of imports.

"The product may be a little bit cheaper if you don't factor in the social costs, the true bottom line in your community -- unemployment, family violence, income disparity, the cost and pollution of burning fuel to bring things all the way across the ocean. These are the real costs, not just what you pay at the pump."

He also is critical of stores that don't find a way to sell products from small producers like his company.

"We can't place our honey because we can't meet their corporate requirements. All they gotta do is set up one table in a corner and say this is to sell Manoa or Hawaiian products. But they want bar codes, guaranteed stock, etcetera. Why have such false standards that prevent the many people who produce stuff here from selling it."

He has no love for politicians who don't support diversified agriculture.

"They support golf courses, development, hotels and water parks, but frankly, diversified agriculture is not getting the support it should.

"Maybe its too long-term vision for these guys. You know farmers have a long-term horizon, they're looking way out there. You plant a tree, you don't get a crop for five to 10 years. Politicians don't like that. They want to see a hotel up and running and a million five in taxes and some kickbacks in two years."

Kliks is generally a happy man. As he shoots his truck up Koko Head Avenue, he points at the hill behind the Kaimuki Fire Station. "Lots of bees in there. This whole area has so many," he marvels.

The information bubbles from him, like he's sharing wonderful, precious secrets.

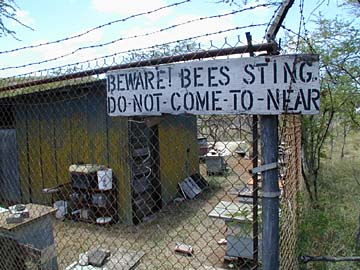

At the hives near Diamond Head, he and Yano don their bee suits -- white because "bees don't like dark colors" -- helmets with netting to cover face and neck and long, thick gloves.

Yano likes the work. "Easy money," he laughs.

"It was scary at first," he admits, "but I wanted to learn. It's good honest work, and you're not cooped up in the office. We're outside, lifting and moving and seeing the countryside."

The agenda this day is to check the honey production in each of the dozen or so hives.

Yano prepares the smoker, a canister with a pitcher-like snout. He pulls on the handle and smoke from a fire inside puffs into the air.

Bees, when exposed to smoke, think fire is about to destroy their hive. So they fly inside to take in as much honey as they can in preparation for fleeing. The honey, Kliks says, makes them more docile.

In the summer, when there are more flowers and more nectar for bees to collect, honey production increases. The two men peer warily into a hive they thought they had taken too much honey from on the last pass. They are pleased to be wrong.

"Man alive, they're doing a job!" Kliks exclaims.

"Look at that!" Yano, pleased with the quantity of honey.

At another hive, the combs are so heavy with honey Kliks needs Yano's help to lift the box.

"Craig, Craig," he calls. "I can't do this alone, man." Both of them grunt to lift the 70 pounds of cumbersome hive box.

"This is a very strong hive and that's good," Kliks says. "It's good and it's bad: good because they protect themselves and fill the honey up quickly, bad because if you have any trouble with them, they get aggressive very quickly."

Earlier, he explained that if one bee is hurt or killed, it gives off a pheromone that alerts all the bees in the hive. When danger passes, guard bees emit pheromones that tells others all's well again.

When worker bees want a new queen, they produce a special substance called royal jelly and feed it to a larvae. Only larvae that gets this jelly becomes a queen.

"It's the workers who decide on the term of a queen," he says. "A very api-cratic society, they have."

Despite his criticism of its politicians, Kliks loves living in Hawaii.

"I'm not going to leave again -- no more research projects in countries that are going to have revolutions, killing and starvation. I've seen too much of that."

This was especially true in Cambodia, where he worked for the Black Star agency as a photographer during the Vietnam War.

He found the job after he was forced to leave Thailand. His fiancee came from an elite family whose patriarch was a major general in the Thai army. The family was not pleased that their daughter planned to marry a foreigner.

One day, military guards handcuffed him, put a hood was over his head and threw him into a car. His fiancee was also taken away and placed in a mental institution.

"I could hear her screaming and yelling." The memory, though three decades old, brings tears.

He was driven around, beaten and dumped in the middle of Bangkok. Eventually, he made his way to the U.S. Embassy.

An official listened to his story, made some inquiries and told him, "Son, if I were you, I'd leave the country."

So he did, flying to Hong Kong where he looked up photographer friends and latched onto the photography job."Frankly, I didn't care if I died at that time. I just lost Susie and it looked to me as if it was hopeless. I was willing to take some risks."

The risks included dodging bullets and seeing the start of Cambodia's killing fields.

"I was principally supposed to cover refugee, ethnic and religious problems. But it was all bound together.

"I saw a river that was full of bodies, floating down by the thousands. Cambodians killing Catholics, Vietnamese slaughtering Cambodians and on and on."

"Oh, yeah, I was lucky, I survived. Guys on both sides of me got whacked. I didn't get even get a wound, nothing."

Lucky, because after a few months, he received word from Susie, telling him everything was all right and to return to Thailand.

They were married and soon had a daughter, Malissa. They lived in Chiang Mai for about three years, but returned to the United States to pursue their doctoral degrees.

Six years later, the couple divorced and Kliks continued his traveling and researching around the globe, taking Malissa with him when he could.

When he returned to the United States, he set up a lab here to provide confidential AIDS testing, but was shut down by the state because he would not comply with regulations to counsel patients before giving them their test results.

Since then, he has remarried, is helping raise stepdaughter Steffanie, and has reconnected with bees, an interest that has been with him since his childhood on the Oregon coast.

"My brothers and I use to go and rob out wild bee colonies in trees. We'd put burlap bags over our heads and smoke 'em and grab the honey, run away with it, and take them home. We called ourselves bee charmers."

"I've live a charmed life. My mother always told me I had a guardian angel. I think my guardian angel now is Dolores, my wife. She really keeps me from the brink.

"If you want to live life to the fullest, you're always on the edge. You have to be or you're not looking down, you're not seeing what's there and what's behind.

"Dolores gives me the capability of being secure."

Click for online

calendars and events.