Saturday, July 24, 1999

Sensational Massie trial

illustrates the need for unfettered

judiciary that won’t bend

to political pressureBar association's plan could compromise fairness

Editor's note: The following is excerpted from a paper presented

to the Social Science Association in Honolulu on June 1, 1998.By Ronald T.Y. Moon

Special to the Star-BulletinHISTORICALLY, in this country, there has always been a certain level of criticism of the judiciary, which, in a free society, is inevitable. Recently, however, there have been unprecedented attacks upon judicial institutions and judges at both federal and state levels by politicians, the media and others, because of the court's unpopular decisions, emotional reactions to those decisions, or both.

Such attacks create suspicion and mistrust of judges and of our judicial system, which, in turn, undermines judicial independence and threatens the delicate balance of power necessary to maintain our democratic form of government.

Unfortunately, the concept of judicial independence and the importance of preserving it are often mystifying and/or misunderstood by the public.

Just what is judicial independence? It means that judges must be free to make their decisions without fear of reprisal. In other words, a decision must be based solely on the legal merits of a case -- not on popular opinion polls or surveys, the views of special interest groups or even a judge's personal preference.When judges are perceived as formulating their decisions in response to political pressure or the perceived majority opinion of the moment, our system of government is placed in serious jeopardy.

Unfortunately, judges are easy targets for those who are intent on tainting them and their rulings with unwarranted, misleading and unjustified criticisms. But who cares?

By attacking the integrity and independence of the judiciary, politicians, the media, special interest groups and the like threaten to undermine the delicate balance of power, which, left unchecked, has the great potential of essentially transforming our three branches of government into two.

Should this occur, the nation would be left vulnerable to the passing whims of partisan politics that now dominate the executive and legislative branches.

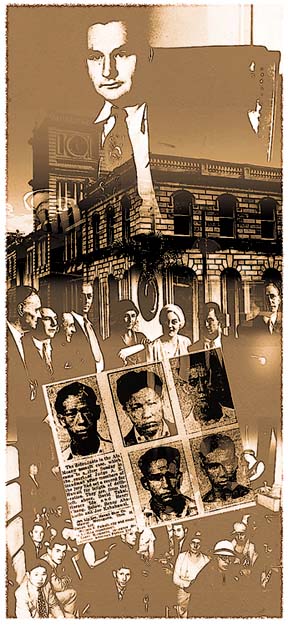

1. Judge Charles Davis resisted pressure from the territorial governor and the U.S. Congress and sentenced the defendants in the Massie case to 10-year terms, which were later reduced to one hour by the governor.

2. Hawaii territorial courthouse where the trial took place.

3. Thalia Massie, in white hat, is flanked by her mother and husband, defendants in the case. Attorney Clarence Darrow is at far left.

4. Police photos of the men arrested in the attack on Thalia Massie. Joseph Kahahawai is at bottom right corner.

5. Public interest was intense. Hundreds of people waited outside the courtroom every day to witness the trial.

Although such an unthinkable result may seem impossible, the events surrounding two famous cases tried in Hawaii over a half century ago demonstrate that such a result could have occurred but for the independence exhibited by a young territorial judiciary. "The Ala Moana Case" and "The Massie Case," as they have been commonly referred to, were tried in an atmosphere highly charged with racial overtones and chauvinistic class distinctions.

However, despite extreme external pressures, the manner in which these two cases were handled nearly 67 years ago is indeed a testament to the ideals and importance of judicial independence.

In the early morning hours of Sept. 12, 1931, Thalia Massie, the young wife of a Pearl Harbor Navy lieutenant found along a secluded area of Ala Moana Road, claimed she had been repeatedly beaten and raped by five local youths.

Thalia was the daughter of Maj. Granville Fortescue, a retired Army officer, who had served as an aide to President Theodore Roosevelt and who was once one of his Rough Riders. Her mother, Grace Fortescue, was the niece of Alexander Graham Bell and was well-known in Washington's influential social circle.

Eventually, five young men -- two Hawaiians, two Japanese and one Hawaiian-Chinese -- were arrested and charged with rape.

When news of the alleged crime reached Rear Adm. Yates Stirling Jr., commander of the Navy in Hawaii, he reportedly exerted continuous pressure upon then-Gov. Lawrence M. Judd to have the case vigorously prosecuted without delay. In those days, the military, especially the Navy, had powerful influence in the community.

Within two months of the alleged rape, the Ala Moana case proceeded to a jury trial. After three weeks of conflicting testimony and four days of deliberation, the jury was unable to reach a verdict. A mistrial was declared, and the defendants were released, pending retrial.

News of the mistrial spread quickly, both locally and throughout the mainland. Criticisms were bitter and fraught with charges similar to those of Admiral Stirling, who blamed the mistrial on racial bias.

Many, locally and on the mainland, shared Stirling's sentiments that the mistrial was a travesty of justice. A prime example -- the General Assembly of Kentucky, the Massies' home state, adopted a resolution calling upon President Hoover to exercise his power as commander-in-chief to demand the conviction of the five Hawaiians or, alternatively, to declare martial law in Hawaii.

Outside investigations

The attacks on the territory's justice system flowing from the mistrial resulted in two formal investigations.Pursuant to a resolution adopted by the U.S. Senate on Jan. 11, 1932, the first was conducted by a team appointed by U.S. Attorney General William Mitchell, and headed by his assistant, Seth Richardson.

The resolution called for the AG to report to the Senate regarding the administration and enforcement of the criminal laws of the Territory of Hawaii and to make recommendations, if any, as to any changes in the Organic Law of the territory that were deemed desirable for the prompt and effective enforcement of justice in Hawaii.

The Organic Act, passed by the Congress in 1900 after the annexation of Hawaii, was the basis upon which the territory's self-government had been established.

The second investigation was conducted by Pinkerton's National Detective Agency Inc. of New York at the request of Governor Judd, who hoped to combat the misinformation being circulated on the mainland about the Ala Moana case.

Reports rule out racism

The Richardson Report clearly destroyed Admiral Stirling's evaluation and conclusion that the mistrial was racially based.The report stated that "the jury panel...was thoroughly investigated and found to be fair-minded, of intelligence, honest, and utterly lacking in any trace of racial bias."

The report pointed out that, although the jury consisted primarily of men of mixed and Oriental blood, most voted to convict the local defendants. The most revealing factor in the report indicated that "the only white man on the jury voted to acquit."

The Pinkerton Report confirmed that the evidence -- or the lack of it -- raised serious questions regarding Thalia's credibility and whether the defendants were even near the scene at the time of the alleged offense.

Calling into question the fact that Mrs. Massie was unable to recite details regarding the attack immediately after the alleged offense, but was able to do so at the time of trial, the Pinkerton Report concluded in part that "we can only assume that ...she did not possess (the details) at the time she was questioned by those she came in contact with immediately after the alleged offense."

After investigating the defendants' alibi defense, the Pinkerton Report concluded that "the movements of the accused on the night of the alleged assault remain precisely as they were originally accounted for," that is, that they were nowhere near the scene of the alleged offense. Unfortunately, the Richardson and Pinkerton Reports were not published until several months after the mistrial.

It appears that the misinformation and misleading conclusions that surfaced soon after the Ala Moana case created such an atmosphere of suspicion, mistrust and lack of confidence in the territory's justice system that, on Jan. 8, 1932, 31 days after the mistrial was declared, Thalia's husband, Thomas, and her mother, Grace Fortescue, with the help of two Navy enlisted men, kidnapped Joseph Kahahawai, one of the defendants in the Ala Moana case.

While the kidnappers allegedly attempted to coerce a confession from him, Kahahawai was shot and killed. Thomas and his mother-in-law, along with the two Navy men, were eventually arrested.

Judge showed courage

A number of books have been written and even a movie titled "The Black Orchid" was produced about the Ala Moana and Massie cases. However, I do not believe that much, if anything, was written or depicted about one aspect of the case which revealed that but, for judicial independence exercised by a judge, the defendants in the Massie case may never have been brought to trial.I refer to the grand jury proceedings that began on Jan. 21, 1932. After two days of presentation, the grand jury was asked to return indictments of murder and kidnapping.

After deliberating for 90 minutes, the 21-member grand jury panel -- 19 of whom had Caucasian last names, one Hawaiian and the other a Chinese last name -- reported to Territorial Circuit Judge Albert Cristy that they could take no action on the matter.

Ordinarily, the proceedings would have ended there, and the defendants set free. However, greatly disturbed by the grand jury's message, Cristy, in an unusual action that could have been criticized as interference with the grand jury process, addressed the jurors, reminding them to lay aside all racial prejudices and to apply themselves coolly and impartially to the question presented to them. The grand jury later returned indictments for murder in the second degree as to each defendant.

The Massie defendants retained the services of Clarence Darrow, who was then 75 years old and in the twilight of his legal career. At trial, Darrow advanced the theory that Thomas became temporarily insane at the moment he allegedly heard Kahahawai exclaim, "Yes, we done it."

Although the defendants were charged with second-degree murder, the jury eventually returned a verdict of manslaughter, with a recommendation for leniency as to each defendant.

Immediately after the verdict was issued, Governor Judd began receiving pressure from Washington, D.C., to pardon the convicted defendants. A telegram, sent by Henry Rainey and B.H. Snell, majority and minority leaders, respectively, of the House of Representatives read, "We, as members of Congress deeply concerned with the welfare of Hawaii, believe that the prompt and unconditional pardon of Lieutenant Massie and his associates will serve that welfare and the ends of substantial justice. We, therefore, most earnestly urge that such pardon be granted."

Martial law was feared

Governor Judd, who also received an identically worded telegram sent by 103 members of the House of Representatives, believed that these telegrams strongly intimated that the future of self-government in Hawaii would be in jeopardy unless he pardoned the four convicted defendants. These "threats" by Congress to make Hawaii a military outpost appeared real, and Hawaii was seemingly at its mercy.About a week later, despite the jury's recommendation and the high-level pressures on the judge to be lenient, judicial independence once again prevailed as the judge, Charles Davis, sentenced each of the defendants to a 10-year term of imprisonment at hard labor.

The sentence, however, was immediately commuted by Governor Judd to one hour in custody, which effectively also terminated the Ala Moana rape case. Three days after the governor's commutation, Thalia Massie, along with her husband and mother, returned to the mainland, leaving the prosecution without a complaining witness.

Judiciary withstood the test

In a University of Hawaii Law Review article, revisiting the Ala Moana and Massie cases, retired Associate Justice Masaji Marumoto underscored the triumph of judicial independence, stating:"The judicial system in a young territory far removed from the nation's capital operated strictly in accordance with the mandate of Congress as expressed in the Organic Act which provided that the Constitution...of the United States...shall have the same force and effect within the said territory as elsewhere in the United States. To its everlasting credit, the judicial system in Hawaii did not deviate from that mandate, despite pressure from higher authorities to do so."

I hope that I have helped foster an understanding of why every individual in our society should care about preserving and maintaining judicial independence. Be mindful that judicial independence is not, as some may believe, for the protection of judges.

It is for the protection of our society against those who commit crimes, the protection of our free enterprise system, and the protection of the rights that every citizen is guaranteed under our state and federal Constitutions.