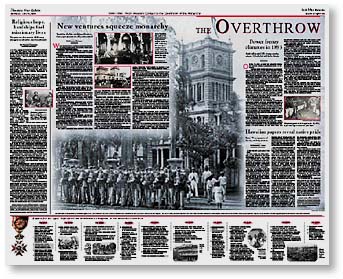

Incoming whalers, sandalwood

By Richard Borreca

traders, then sugar growers

steadily gain control

Star-BulletinWith the novelty soon waning, Hawaiians found that foreigners moving into Hawaii were rapidly grabbing irreversible control.

Explorers, then missionaries and traders. Asian merchants came looking for sandalwood. Whalers came next.

By November 1852, Honolulu Harbor was a forest of masts as 124 whale ships and 23 merchants crowded the harbor. More than 3,000 seamen were suddenly ashore, looking for liquor and diversions.

Drunken brawls led to arrests. The death of one sailor, killed while in custody, prompted a three-day riot. The police station at the harbor-end of Nuuanu Avenue was burned; sailors forced their way into the homes of Honolulu residents. Order was not restored until 200 local citizens volunteered to patrol the streets.By 1850, the hub of commerce for the entire north Pacific was Honolulu.

The whaling industry had replaced the sandalwood trade. With it came a rising demand for many things: wood, rope, water, salted beef, pigs and chickens, tools and cloth. Whalers shipped supplies and their rendered whale oil and bone through Honolulu.

Soon, men left the ships to open stores. The children of missionaries who began coming in 1820 stayed in the isles and became active in commerce.Hawaii was getting accustomed to its boom economy. After sandalwood had peaked and before whalers depleted the North Pacific of the huge animals, Hawaii also was reaping a boom selling goods to the growing population in California, site of the 1848 gold rush.

For local consumption, companies such as Theo H. Davies, Castle & Cooke, H. Hackfeld, and C. Brewer bought and sold new items needed by the just-forming plantations.

Come 1861, Hawaii again benefited from events outside its control, as the American Civil War caused a demand for sugar which Northern states could no longer get from the South.

In 1859, Hawaii exported nearly 1.83 million pounds of sugar; in 1884, that figure soared to surpass 10.41 million pounds.

"The sugar industry was the prime force in transforming Hawaii from a traditional, insular, agrarian and debt-ridden society into a multicultural, cosmopolitan and prosperous one," local historian Carol Wilcox wrote.

The sugar plantations were Hawaii's first stable economy. Unlike the sandalwood traders who stripped the forests, or the whalers who killed the animals into near extinction, sugar replenished itself.

Growing sugar, however, was not a simple task --it took a lot of labor, land, water and machinery to produce a profit-making product. So it was that Hawaii's new agricultural economy flourished with men who made and executed big plans.

On Maui, for instance, James and Samuel Alexander and Henry Baldwin formed the Hamakua Ditch Company, forerunner to the East Maui Irrigation Co. They brought water throughout the island to make the cane grow, and they were unstoppable.

Two years earlier, Baldwin had lost an arm while checking the gauge of the rollers at his sugar mill --but it didn't prevent him from working on the ditch. When workers refused to rope over the side of a cliff to place machinery, Baldwin, clutching the rope with his leg and his one arm, went down and so shamed the men that they followed him.Tough as they were, those early planters needed help --political help - if they were to keep the plantations profitable. They needed the ability to sell sugar in the United States without paying a tariff --the reciprocity treaty.

Pressure was increasing on the monarchy. More and more of the court was filled with foreign advisers. The Hawaiians opposed reciprocity, fearing it was the bait to give the United States exclusive use of Pearl Harbor.

When Kamehameha V died in 1872, he left no successor after Princess Pauahi declined his deathbed offer to become queen. To continue the monarchy, an election was held, and Hawaii changed again.

As king, William Lunalilo affirmed his support for reciprocity but it outraged his Hawaiian supporters, who feared it would mean ceding land to a foreign power. The actual treaty, signed by Lunalilo's successor in 1876, did not include use of Pearl Harbor -- though upon its renegotiation, exclusive use of the important future military base was granted to the United States.

Elected by the Hawaiian Legislature after Lunalilo's death in 1874, King David Kalakaua was a hard-nosed individualist who appreciated more than he could afford. Iolani Palace was completed during his reign and he held a coronation ceremony on its grounds, crowning himself in the manner of Napoleon.

His adviser, San Francisco sugar refiner Claus Spreckels, bought his way into power by supporting and encouraging Kalakaua's pet projects. The bankroll came with a high interest rate, however, and the kingdom and its king found themselves in debt to Spreckels, who finally was bought off and left Hawaii.

In 1890, an ill Kalakaua traveled to California for treatment, leaving his sister Liliuokalani as regent. When he suffered a stroke and died early the next year, she became queen -- Hawaii's last monarch.

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin is counting down to year 2000 with this special series. Each month through December, we'll chronicle important eras in Hawaii's history, featuring a timeline of that particular period. Next month's installment: July 12. About this Series

Series Archive

Project Editor: Lucy Young-Oda

Chief Photographer: Dean Sensui