Hokule'a is on the

By Susan Kreifels

voyage of the century, a journey to

isolated Rapa Nui, where a Polynesian

renaissance is coming alive

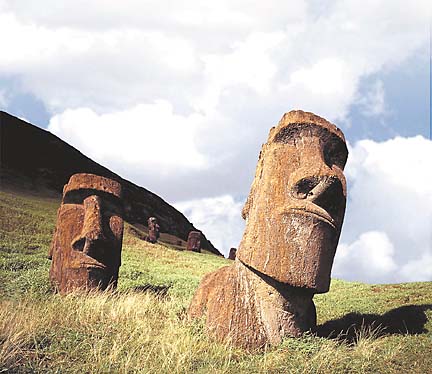

Star-BulletinWhen students from Kamehameha School visited Easter Island last year, they approached the famous stone heads known as "moai" with chants of respect for the Polynesian ancestors who carved them.

They brought seedlings to reforest the isle and heal the land.

That respect for the ancestors and environment was not lost on the native people of the place they call Rapa Nui. Like the local man who always used the statues as a place to tie his horse. After the visits of the Hawaiians, he started to look at the magnificent carved heads with different Polynesian eyes.

"It was a powerful thing," reflected Sergio Rapu, one of a handful of Rapa Nui natives who live in Hawaii. "We don't respect our things. They had so much respect."

This month, the Hokule'a, a traditional voyaging canoe symbolizing a renaissance of Hawaiian culture in the last 25 years, sets sail for Rapa Nui, the last voyage of the century. It will complete the triangle of ancient Polynesian migration routes retraced by it and two other Hawaii canoes.It's also the most difficult voyage. Against prevailing winds and without the aid of navigational equipment, depending only on the stars and other signs of nature to guide them, the Hawaiians will travel 1,450 miles from Mangareva to the 50-square-mile Rapa Nui, the most isolated inhabited island in the world.

Like native Hawaiian culture was lost to the missions and U.S. colonization, so the ancient Polynesian culture of Rapa Nui disappeared in a web of Chilean and Spanish influence.

Rapu, a former governor of the Chilean territory, looks to Hawaiians to help inspire a renaissance of Polynesian culture and pride in his home island.

He calls the visit of the Hokule'a a "great gift of tremendous symbolic value, a dream come true" for the native people who make up two-thirds of the island's 3,000 residents.

Nainoa Thompson, captain of the Hokule'a, has become a hero there as well after a visit last year to teach canoe-paddling. Rapa Nui now has a canoe club, and locals traveled on a Chilean navy ship through the Pacific to learn about traditional Polynesian navigation.

Rapu, also director of the island's Institute of Pacific Study, which trains people for modernization, believes the Hokule'a voyage will entice the Rapa Nui community to look more to the Pacific than to Chile, "to think differently about the environment and culture."

Rapu is a University of Hawaii-trained archaeologist who has helped restore the giant "moai" over the last 25 years. He takes pride in his ancestors, calling them the "ultimate Polynesian carvers."

But he uses the loss of language as a gauge of his people's cultural demise: 30 years ago, 75 to 80 percent of the locals spoke the native language, which evolved from the ancient Polynesians. Today, 25 percent do.

Much has changed since the first commercial flight arrived on Rapa Nui in 1968, and since the government realized the tourism value of the moai. About 20,000 tourists arrive every year.But the loss of Polynesian culture started centuries earlier with the arrival of Dutch explorers in 1722, followed by the Spanish and French. Catholic missionaries from Tahiti came in 1864 and bishops convinced the Chilean government to take more interest in the island, which it eventually annexed and leased to a private sheep rancher.

In 1933, Chile declared the island state property and made it a historical monument two years later because of archaeological and scientific interest from abroad. In 1966, the people became Chilean citizens, and administration of the island was taken away from the navy.

About a quarter of the native people work for the Chilean government, which subsidizes all education and university fees.

Alejandra Adolpho, 27, moved to Hawaii from Rapa Nui in 1992 to study at Brigham Young University in Laie, and married here. She counts herself lucky that her grandmother taught her the native language and ancient history of her home.

In the last two years she's seen "a little light" of cultural revival among her friends and the way they want their children educated. She sees the voyage of the Hokule'a as "a boost for the people. Not only are they trying to restore culture and language, but there are other Polynesians already doing this.

"This is a wake-up call to everyone. There are things they need to take care of before our kupuna (elders) truly pass on and we don't have any more people to go to for oral history, all the things you don't find in books."

Sources: NOVA Online; World Book Encyclopedia; Polynesian Voyaging Society

ON THE WEB

Hokule'a: Follow the voyage of the Hokule'a at: http://leahi.kcc.hawaii.edu/org/pvs.

Easter Island: Photos were provided by Cliff Wassmann, who specializes in documenting sacred sites and ancient civilizations. More of his work can be seen at: http://www.mysteriousplaces.com