Dana's death has dramatically changed

By Cynthia Oi

the lives of her parents, sister and friends,

who may never have closure

Star-BulletinSpringField, Va. -- In the delicate light of an early spring morning, John Ireland settles on a blue blanket spread over the new-green lawn that slopes from his house to the street.

Yellow bursts of forsythia, pink flutters of cherry blossoms, a tickling scent of budding leaves fulfill the promise of the season. The colors of earthly renewal surround John as he tends his garden, yet a gray sadness veils him.

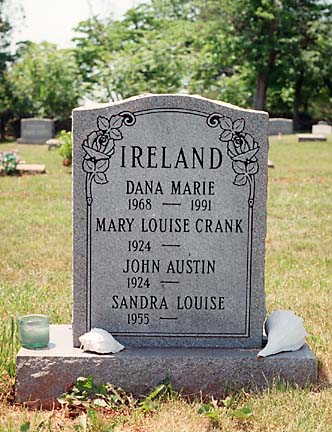

Eight spring flourishes have come and gone since his daughter was killed. Eight Christmases, too, a measure more precise because in the cruel, random chemistry of murder, Dana died in the first minutes of Christmas Day 1991.

It's a lie, John says. Time does not heal all wounds. Not his. Not her mother's. Not her sister's. Time may have dulled the brutal details of her death, but the pain remains a vivid slash.

Yes, other parents have lost children in horrible murders. That Dana's was one of thousands doesn't soothe their anguish. Dana was their girl.Her murder envelops them.

On the surface, very little separates Louise and John Ireland from the other residents of Springfield, a Virginia suburb about 11 miles southwest of Washington, D.C. They shop at the mall, take walks down the street, get the air-conditioner checked before summer, pick up the mail from the floor when the postman drops it through a slot in the door.

Their house of tan bricks and white siding echoes others on the looping roads through the hilly neighborhood.

Inside the tidy home are the distinctions. No fewer than 18 photos of Dana -- at various stages of her 23 years of life -- sit on dust-free shelves and tables in the living-dining area. Downstairs in the family room are her soccer trophies. In bedrooms upstairs are neatly arranged stuffed animals, furniture, a 1991 calendar and other belongings, all unneeded reminders.

"I died when Dana died," says Louise. "I died when she did." She will repeat this through several conversations, but it is not a pat sound bite. The murder has stopped her life in one place like a needle stuck in the groove of a record.

Proud mother

At 75, Louise is slim, straight-backed and snow-haired. Her accent traces a Virginia upbringing as does her graciousness, serving visitors homemade peanut-butter cookies and fruit platters. Her fastidious clothing -- white turtle neck under a blue sweater and black-and-white checked slacks -- are unremarkable except for the small silver-framed photo of Dana pinned above her heart.Louise talks about Dana matter of factly, outlining her daughter's accomplishments, her personality, her favorite things. She shares boxes and albums of photographs, sometimes struggling to recall the wheres and whens of so many pictures.

She finds a term paper Dana had written for a college class and reads it aloud: "It was the happiest day of my life and the saddest. ..."

She cannot get beyond that first sentence. She presses the tissue she's been holding in her hand over her blue eyes and weeps, her grief as fresh as yesterday.

Louise wasn't always like this.

Profound change

Valerie Oliver remembers another Louise she called Squeeze. Val and Dana met when both were in the sixth grade and Val's family moved in across the road. Val spent countless hours playing at the Ireland home, and the familiarity spawned the nickname for her pal's mom.

"Squeeze used to be so funny," Valerie recalls. "She was wonderful to be around. Now she's just very, very sad. It's hard to be with her. She is a completely different person."

John and Louise, married for 45 years, have a kind of rhythm long-together couples develop. Telling a funny story about Dana, both laugh and exclaim at the same parts. But soon the laughter fades and their eyes regain the haunting.

John's brother, Bob, believes Dana's murder has put "somewhat of a wedge" between the couple. "It's difficult for me to say this, but I think it has driven them apart. I don't think they're quite as close to one another as they once were."

In life, Dana was Louise's "love and joy," he says. In death, she has become her only focus.

"I used to enjoy Louise," he says. "But she has become so obsessed with this that after awhile you wish she could change the subject."

Louise isn't unaware of this perception.

"Some of the time, people I talk with -- my family, somebody -- they don't want to really hear this stuff. Maybe because they think it might come off on them," she says.

"There's people I used to play golf with for years who have never called again," John says. "People avoid you."

People sympathize, he says, but a lack of understanding sometimes makes them cruel.

"I had a call from a television newscaster in Honolulu. She asked me whether there was any difference between losing a child in an automobile accident or by murder. My only comment was I can't tell; I never lost a child in an automobile accident."

Louise keeps occupied "by shopping."

"And taking it back," John interjects. "She buys these things and turns around and returns them."

"I have to do that to keep my mind," Louise says. "But I can't turn my back on what's happened."

Neither can John. He makes his way through by working for victims' rights, talking to students and community groups about crime, participating in seminars, pushing legislation and helping others who share his misfortune.

"It helps me," he says simply.

Pillar of strength

Where Louise is visibly emotional, John is deliberate."He thinks things out," says brother Bob, who lives in Florida and Pittsburgh. "He considers everything before he does something. He was always that way, more or less. John has held up better."

John's resilience may come from weathering a difficult childhood. When he was 4 and Bob 3, their mother died. Their father found it too difficult to raise his five children by himself, so he took them to his mother's home in Pittsburgh.

"It was rough on my grandmother," recalls Dolores Ireland Dooley, their sister. Bob and John were placed in an orphanage. John spent most of his years before high school "in one home or another."

"We were just the poor orphan cousins that got shoved from one household to another. Maybe that's why John was strong enough," Dolores said.

Whatever the source, Dana's father is tough. He isn't a big man but his shoulders are straight, his body fit with only a hint of a paunch at waistline. His white hair and beard are neatly trimmed.

John is a reasonable man. When he thinks others aren't -- like the Hawaii state House members who failed to move on a bill to remove a statute of limitations on certain felonies -- he is disappointed.

"I can see no reason or justification for dismissing the ability to prosecute someone for a violent crime just because there's a law that says six years and you're free," he says.

He is compassionate. Bradley Lauve, a student at Dana's alma mater, George Mason University, had mixed feelings about winning the scholarship the Irelands set up in Dana's name; it is awarded to someone whose family has been affected by a murder. Lauve's sister was a victim.

"I told Mr. Ireland I wasn't sure how to react to getting money for losing a family member, to be in that category to qualify. It was free money for something I really didn't want free money for," says Lauve. "He told me to take it and do every good I could for Dana and to do everything for my sister. He helped me through."

John is cool. Around midnight one night in 1994, he was sleeping when the phone rang. Louise answered. It was Frank Pauline, one of the men accused of killing Dana, wanting to speak to her father. Instead of raging against him, John questioned Pauline. "I asked him why he didn't call the police when he saw this (killing) and he said he was afraid. ... All he was trying to do was get special treatment."

Pauline called collect. It cost the Irelands $4.04; they still have the phone bill.

John, 75, is a wounded man. He maintains his emotional balance, talks evenly about the facts cataloged and filed in his mind. Then something cuts loose and the pain emerges. "It's Christmas Eve, Christmas Eve!" he says. "What kind of people -- on Christmas Eve -- who does this?"

Dana's sister hurting

The Irelands' older daughter, Sandra, is also scarred.She had lived on the Big Island for about 15 years, attending the University of Hawaii at Hilo, then working in agriculture before setting up a business with her boyfriend, Jim Ingham, raising palm trees.

"Sandy will not go back to the Big Island anymore," John says. "She loves Hawaii, but she'll never go back."

Now in her early 40s, she and Jim, whom she later married, live a nomadic life, sometimes staying in Oregon, other times in Wyoming. She received part of the $452,000 settlement her family was awarded in a negligence suit brought against Hawaii County. (The rest went to the scholarship fund and to her parents.)

"She doesn't have children," Louise says. "No, she said after what happened to Dana she didn't think she could raise a child."

Sandra can't talk much about her sister.

"Every time I think about her, it circles around. Going through all the good memories brings up a lot of real stuff as well," she says.

"It's funny; the further away it gets the harder it becomes. It actually feels worse now."

She's aware of the toll on her parents. "For my mom, I can see that with her it may not be as intensely painful, but the pain is more chronic.

"As they get older, this thing weighs more heavily on them. But they're real troupers," she says.

Sandra was the reason her parents visited Hawaii almost every year, bringing Dana with them. So the "ifs" run through them all. If they hadn't gone to Hawaii, Dana might not have died. If John had insisted that Dana drive that day instead of riding her bicycle, she might be alive today.

'Through the wringer'

The ifs pulse through Mark Evans' mind, too.He was the friend Dana had biked over to see that Christmas Eve. He had no telephone, so she delivered an invitation to dinner that night in person, pedaling down the rough road to his house in Opihikao.

"When she left my driveway, I said, 'Let me give you a ride home. Throw your bike in the back of my truck; I'll give you a ride home.' But she said, 'No, it's a beautiful day, I want to get the exercise.'

"I could have insisted. It still goes around in my head."

His grief for Dana is aggravated by his being considered a suspect initially.

"I've been through the wringer," he says, running his carpenter hands through his dark hair. "I've been through lie detector tests, I've been through saliva tests, followed by the cops. At least once or twice a year, they check up on me -- where I'm at -- and ask me my story again."

Mark had met Dana through Sandra and he projects the ifs to her, too. "Sometimes I wonder like if Sandy thinks if she never introduced me to Dana, she would have never come to my house and she would have never been hurt.

"Now when we see each other, there's this thing that's there."

The Irelands, he said, "don't hold me responsible. But we don't talk, we haven't talked. I spent an afternoon with them once, but what can you say?"

Grief, second-guessing

Another male friend of Dana's was Jeff Stiles, a fellow student at George Mason University. Although he still lives nearby, he hasn't spoken to the Irelands since Dana's death and he declines to discuss her at all.Louise is understanding. "I've wanted to talk with him, but he never returns my calls. It was so heartbreaking for him. One thing we do know: He goes down to her grave site every year at her birthday and leaves roses there."

Valerie says Jeff "thought the world of Dana's parents, but it's a hard thing from his perspective. Seeing them brings it back like it was yesterday."

Ida Smith did not know Dana until she found her broken body on a fishermen's trail near her Waawaa home. The images of the battered, bleeding young woman are stuck in her head.

Because of Dana, Ida hasn't celebrated Christmas for a long time. "The day after it happened, I went to my son's house for Christmas. All I could do was sit in a chair and cry."

Her notoriety rips at her. "People say, 'Oh, aren't you the one who found Dana Ireland?' It's a terrible thing to be known for."

Ida has her ifs. If she had been strong enough to lift Dana, she could have taken her to the hospital instead of waiting what seemed like endless hours for an ambulance to arrive. The ifs touch her husband, Merrill, too. A big, strapping fellow, Merrill was usually home from work at the time Ida was helping Dana. That day he was late.

"Since then, he has never come home late. He said that if he had been home, he could have helped me," she says.

Ida wants an ending. "This particular business needs closure. It's just as hard now as when it happened. People say time heals all wounds. Time doesn't heal all wounds."

John agrees. "There is no healing," he says, his voice soft and raspy. "You don't heal.

"I'll tell you why: Before there are any arrests, you're concerned that there will never be arrests. Once there are arrests, you're concerned that it won't be a fair trial or that they won't be convicted. After they're convicted, you're concerned about the sentence. After that, you're fighting for the rest of your life to make sure they never get out of jail.

"There is no end to it."

Courtesy of John and Louise Ireland

3-year-old Dana on the patio of the

Irelands' home in Springfield, Va.

Tuesday, June 8

Blurred through the years is the real Dana. She lives on, though -- beautiful, shy, kind -- in the memories of those who knew her. The innocent. The indicted. Anatomy of a murder. The what and where of the attack. Who's who in the Dana Ireland tragedy.

Wednesday, June 9

Help came too late for Dana Ireland. From the moment she was hit by her attackers' car until the time an ambulance reached her, more than two hours passed. Here's how minutes -- and a life -- were lost.

Thursday, June 10

Life has gone on since the Dec. 24, 1991, attack. Memories have faded. Witnesses have scattered. But each twist and turn in the seven-year bid to bring to justice those responsible means fresh injury, not only to Dana's family but to witnesses whose lives have been put on hold by this on-again, off-again case.

No Frames: Tuesday, June 8 | Wednesday, June 9 | Thursday, June 10