Hawaii County officers and detectives

By Crystal Kua

that worked on the case lacked

important resources

Star-BulletinThe Hawaii County police investigation of Dana Ireland's murder has been a formidable task from the beginning, one limited by manpower, money and forensic capabilities.

More than seven years after the murder, even as the trial of one suspect was about to begin, police would still be gathering evidence and making arrests in a case that had the public impatient for a resolution.

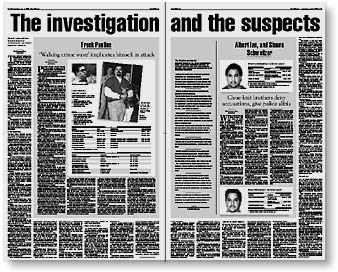

The big break in the case came in a confession by Frank Pauline Jr. in June 1994. Until then, the investigation appeared to have stalled, with police hitting dead ends on the tips and rumors they had received.

Police also have had a public-relations problem. Medical assistance to the battered woman had been delayed, calling into question the competence of Big Island authorities. Her parents sued the county over the delays, settling out of court in 1996.

Dana's parents, stung by what they saw as indifference by law enforcement officials, began a campaign to keep the case at the forefront of public attention. When two other high-profile murders occurred within two years of the Ireland killing, people began to doubt if police could keep them safe.The integrity of the investigation is expected to play a pivotal role next month in Pauline's trial and in the case against brothers Shawn and Albert Ian Schweitzer, who were reindicted last month in the murder.

A bad beginning

That Dana Ireland was assaulted on Christmas Eve was more than an unfortunate emotional flash point. Because it was a holiday, police manpower in the Puna district was stretched thin.Puna is mostly rural, and, at 499 square miles, it is nearly the size of Oahu. At the time of the murder, about 350 sworn police personnel were responsible for all of the Big Island. Comparatively, Oahu is policed by about 1,900 officers.

Only two officers and a sergeant were assigned initially to respond to the two crime scenes involving Dana -- one at Vacationland where she was struck by a car, and the other in Waawaa, where she was dumped. Although separated by just five miles, the sites are linked by rough road, parts of it unpaved.

Police records show that the first Puna patrol officer, Robert Wagner, arrived at Vacationland within 11 minutes of an emergency call. Officer Harold Pinnow and Sgt. Gabriel Malani arrived four minutes later.

Shortly thereafter, another emergency call sent Pinnow to Waawaa because no other officers were available to respond, police officials have said. Dispatcher Donald Brescia testified in a 1993 deposition that normally there were at the most two officers assigned to the area.

The holiday also made it difficult to contact detectives and ranking police officials who were off duty.

James Day, then a Hilo patrol lieutenant and now the captain of the criminal investigation division, was frustrated that he couldn't find CID and Puna patrol officials to handle the situation.

"We tried the beeper. We cannot get ahold of anybody," he said in a conversation that night.

In addition to the lack of officers, the investigation was hampered because the first people at the sites were civilians.

Victor Vierra, who was county police chief at the time of the murder, said securing a crime scene is important in preserving evidence.

Although he declined to speak specifically about the Ireland case because of a court-imposed gag order, Vierra did talk generally about police procedures in place during his tenure as chief.

When a crime scene is secured, detectives are able to go over an area inch by inch in search of evidence, he said.

But when people trample over a potential crime scene, evidence may inadvertently be moved or destroyed, he said. "It definitely hinders an investigation."

Anna Sherrell came across the Vacationland site as she drove to Pahoa from her nearby home. When she saw Dana's smashed bicycle, locks of her blond hair, blood, a broken watch and tire tracks in the cinder road, she realized someone had been hurt.

"I was searching for a body. I found the watch, but her hair was hung up on stuff out there ... hair on the bike, hair on the bushes there. I made a mistake by touching everything I picked up," Sherrell said in a recent interview.

Other people arrived, also trampling and touching potential evidence.

Passerby Ritch Trenda had a camera with him and took pictures of the tire tracks. He also tried to direct cars around them, Sherrell said.

John Ireland, the victim's father, said a lot of people were milling around the site when he got there. When the sergeant arrived, he began to get things organized, Ireland said, but police "never cordoned off that site." Even the next day, the scene was left open, he said.

Civilians also gathered at the second scene in Waawaa where Dana Ireland had been left along a fishermen's trail. Ida Smith, who found her, discovered possible evidence nearby -- a boy's shoe and what looked like men's underwear. At least five people came up and down the trail as they attempted to help the beaten woman.

About two and a half hours after Ireland was found, the detectives arrived in Waawaa. Detective Steven Guillermo, who was on standby that day, became the case's lead investigator.

Clues and confusion

After Ireland was taken to Hilo Hospital, where she died early the next morning, her body also provided clues."Once someone dies from a violent encounter, (the body) becomes evidence," Vierra said.

She had a bite mark on the top of her left breast. Vaginal, cervical and rectal swabbings were taken before and after she died and some of the swabbings showed signs of semen, according to court documents. An autopsy showed that she bled to death and suffered vaginal trauma, which is a sign of being raped.

The lack of facilities and funding factored heavily in the police investigation.

The Big Island doesn't have a medical examiner. At the time of Dana's death, the pathologist on duty at Hilo Hospital performed autopsies. The department now contracts outside forensic pathologists who specialize in finding causes in suspicious deaths.

The county in 1991 did not have special technicians who collected and processed evidence, but Vierra said detectives are trained to do the same type of work.

The county has a crime lab, but not one sophisticated enough to test many types of evidence, including substances with DNA, so police rely on such outside agencies as the FBI to analyze material.

The service is free, but not fast. John Pikus, spokesman for the FBI's Honolulu office, said the agency receives hundreds of requests a month for lab work.

"The lab is overworked," he said, and a law enforcement agency can expect to wait six months to a year for results.

The Honolulu Police Department's busy crime lab also does work for neighbor island police, but it charges the per-hour salary rate of the analysts and won't take a case if it can't meet the neighbor island department's deadline.

Private laboratories can do the work much faster. Tests by Forensic Analytical Laboratories of Hayward, Calif., were completed in about a month.

These labs, however, are also expensive, charging from $550 to $1,000 per sample.

Some of the evidence became points of confusion for the public.

The bite mark on the body was compared with samples from suspects, including the Schweitzer brothers.

Of the three defendants, the only one so far excluded as causing the bite mark is Shawn Schweitzer, according to court documents.

In 1994, Dr. Norman Sperber, a San Diego forensic teeth specialist, said Albert Ian Schweitzer could be "ruled out as causing the bite mark seen on the victim." But court documents filed in 1998 say Sperber later changed his opinion after reviewing more evidence from prosecutors and that Schweitzer's teeth were "consistent with the bite mark."

Other evidence in the case includes a bumper found inside of Ian Schweitzer's Volkswagen that had damage consistent with having struck the bicycle, a hair on the VW trunk lip and a turquoise "JimmyZ" T-shirt.

The Schweitzers were indicted in the case in October 1997. A year later, Edward Blake, a DNA expert involved in the O.J. Simpson case, analyzed evidence and found sperm on a hospital sheet the victim was on.

The prosecution sent samples to Forensic Analytical Laboratories, and in October 1998, the lab reported that the sample didn't match the Schweitzers or Frank Pauline Jr.

Charges against the Schweitzers were dropped, but the two were indicted again last month.

Tips and the usual suspects

The day after Dana Ireland died, police asked the public to call in with any information about the case.The family made an appeal a day later and by the end of the week, a reward fund was set up that would eventually total $25,000.

With the money as an incentive, dozens of tips began coming in.

But with only one detective assigned full time to the case and others helping out when they could, the work became overwhelming.

Police found it difficult to sort out the valid information from the rumors. A few months into the investigation they became frustrated at the number of rumors they had checked that didn't pan out. Rumors had "exasperated" the investigation, Assistant Police Chief Leroy Victorine said at the time.

Rumor or not, police are almost always obligated to check out all information pertaining to a case. "You have to follow up. There's no way to know what's legitimate and what's not," Vierra said.

A little more than a month after Ireland's death, a man who wanted to remain anonymous walked into the Hilo police station. He told Guillermo that three brothers were at a New Year's Eve party where they bragged about running over a woman, biting her and sexually assaulting her. The man said he would contact police again because he wanted the reward, but he never did. Guillermo did not recognize the man and had no way of finding him again.

In 1994, veteran officer Richard Marzo said he had passed on to investigators information he considered valid.

Marzo said that two weeks after the murder, he and other Puna patrol officers began hearing rumors that Pauline was involved in the crime. A year later, he arrested two boys who said Pauline had told them where Dana's body was dumped and the description matched the location in Waawaa. He forwarded the information to detectives.

Several months later, he arrested the same boys again and filed another report about Pauline because the boys told him detectives had not talked to them.

Marzo believes his reports had been ignored, but detectives said they had reviewed his information.

"The police in our case have pursued the anonymous 'tips' diligently, many of which have proved to be exaggerated, overheard rumors, or just plain wrong," Deputy Prosecutor Charlene Iboshi wrote in court documents in April. "Some tips have been fruitful."

Police also looked at a dozen or so people as possible suspects.

Among the first was Sherrell, who came upon the crime scene as she drove out of the Vacationland subdivision.

"They had me up like I was a suspect," Sherrell said. She was questioned about where she had been headed that day, what kind of videos she rented, why she was going to dump her trash, why one of the windows of her van was cracked.

Another person questioned at the scene was Mark Evans, the friend Ireland had bicycled over to visit earlier in the afternoon.

Police "asked me a million questions, took my identification," Evans said. Over the years, he has had to take lie detector tests and give saliva samples.

Franklin Alimoot Jr., who lived with his sister and brother-in-law in Vacationland, also was a suspect at one time. Alimoot, who now lives on Oahu, said it was a scary experience.

"In the beginning, they was just blaming us for the whole thing," he said. "I couldn't do that to a woman."

Alimoot had to give dental impressions and answer a lot of questions to prove his innocence, he said. "They would question us for hours and hours. ... My brother-in-law they really harassed. They took his mom's van and checked it for blood."

Police never told him directly that he was cleared as a suspect.

Another person who has been publicly identified as a previous suspect along with his brothers is Wayne Nasario, whose name surfaced this year when he was asked to provide saliva and bite-mark samples for testing.

Nasario and his brothers had been cleared previously by police, but the forensic work confirmed the earlier exclusion, police said.

Police get mixed reviews on how quickly they questioned witnesses.

Geri Gallagher, a nurse who went by the name Geri Coleman at the time, said police questioned her for four to five hours the day after Dana died.

Meanwhile, Hazel Franklin, known as Hazel Allan at the time she reported Dana was raped, said police didn't talk to her until three years later. They told her she "fell through the cracks."

The investigation of suspects, rumors and tips kept the thin corps of detectives busy, even after Pauline's confession. The work continues today as prosecutors get ready to take him and the Schweitzers to trial.

Hue and cry

In the years after Dana's death and before Pauline's confession, police also had to deal with criticism of their work in two other high-profile murder cases: Yvonne Mathison in 1992, the wife of a police sergeant; and Sequoya Vargas, a 16-year-old Puna girl in 1993.That pressure came chiefly from a group called Citizens for Justice, which had pushed for the arrest of Mathison's husband.

In 1994, the group and the Irelands asked the state attorney general to assign a special prosecutor to handle the Ireland case, saying police were taking too long to solve the murder. The request was rejected.

Ireland's family, meanwhile, wrote letters to the newspapers, flew to Hawaii frequently, and kept the heat on police.

"I feel our presence here will keep the fact that the perpetrators are still walking the street in the forefront," John Ireland said in a 1994 interview.

He also complained that the police were not communicating well with his family and that often his requests for progress reports were ignored. His relationship with police improved after a change in police chiefs in 1994, he said.

Vierra said despite progress in the investigations, publicity and media coverage made it look like police weren't doing enough.

"So in the end, it looks like we're not doing a good job," he said. "The public pressure sometimes unfairly puts pressure on (investigators)."

In court documents filed earlier this year, prosecutors declared, "This was an enormous investigation for police."

Courtesy of John and Louise Ireland

3-year-old Dana on the patio of the

Irelands' home in Springfield, Va.

Tuesday, June 8

Blurred through the years is the real Dana. She lives on, though -- beautiful, shy, kind -- in the memories of those who knew her. The innocent. The indicted. Anatomy of a murder. The what and where of the attack. Who's who in the Dana Ireland tragedy.

Wednesday, June 9

Help came too late for Dana Ireland. From the moment she was hit by her attackers' car until the time an ambulance reached her, more than two hours passed. Here's how minutes -- and a life -- were lost.

Thursday, June 10

Life has gone on since the Dec. 24, 1991, attack. Memories have faded. Witnesses have scattered. But each twist and turn in the seven-year bid to bring to justice those responsible means fresh injury, not only to Dana's family but to witnesses whose lives have been put on hold by this on-again, off-again case.

No Frames: Tuesday, June 8 | Wednesday, June 9 | Thursday, June 10